Researchers have given robots a sense of touch via “listening” to vibrations, allowing them to identify materials, understand shapes, and recognize objects just like human hands

Imagine sitting in a dark movie theater wondering just how much soda is left in your oversized cup. Rather than prying off the cap and looking, you pick up and shake the cup a bit to hear how much ice is inside rattling around, giving you a decent indication of if you’ll need to get a free refill.

Setting the drink back down, you wonder absent-mindedly if the armrest is made of real wood. After giving it a few taps and hearing a hollow echo however, you decide it must be made from plastic.

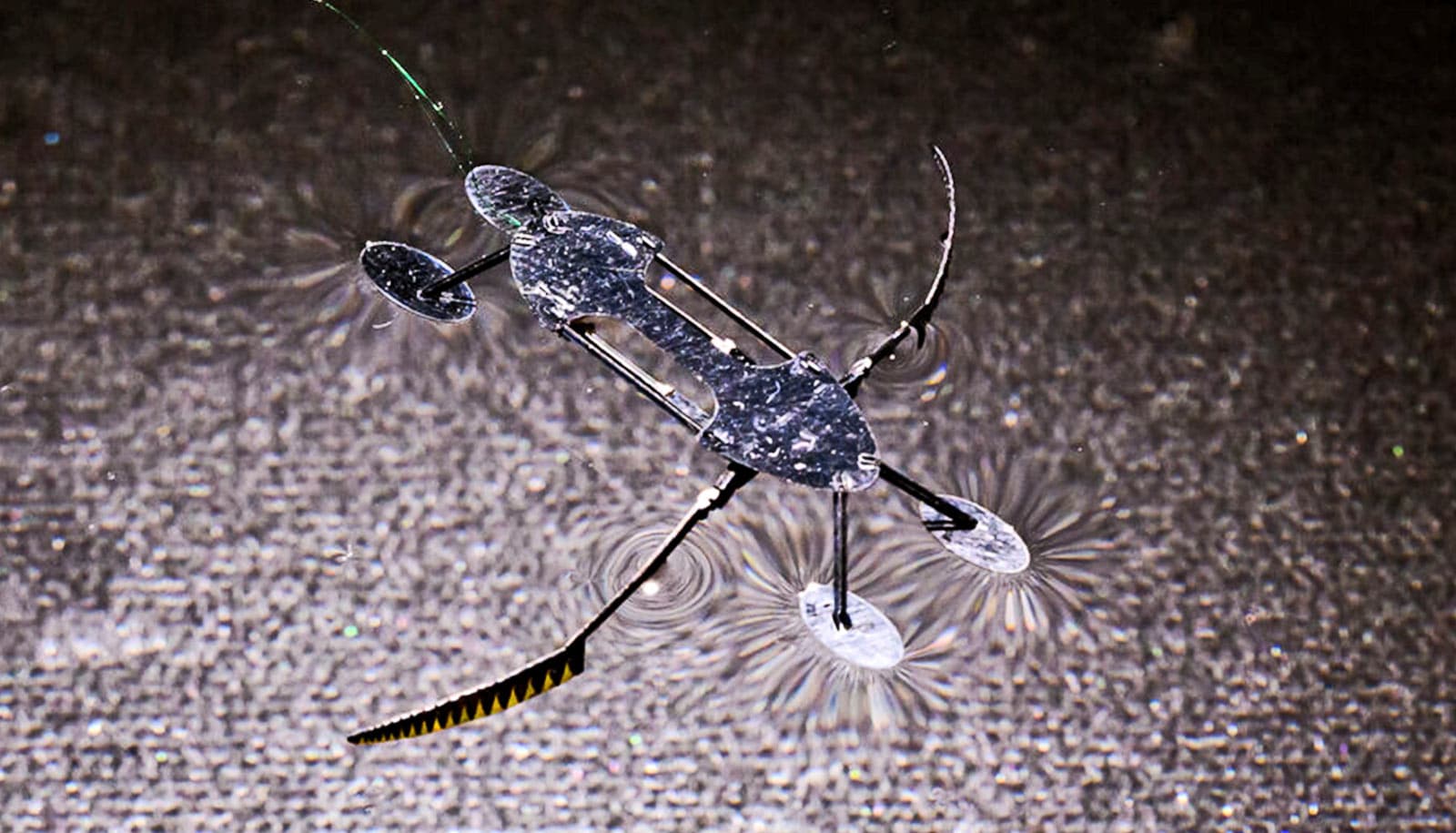

This ability to interpret the world through acoustic vibrations emanating from an object is something we do without thinking. And it’s an ability that researchers are on the cusp of bringing to robots to augment their rapidly growing set of sensing abilities.

Set to be published at the Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL 2024) being held November 6–9 in Munich, Germany, new research from Duke University details a system dubbed SonicSense that allows robots to interact with their surroundings in ways previously limited to humans.

“Robots today mostly rely on vision to interpret the world,” explains Jiaxun Liu, lead author of the paper and a first-year PhD student in the laboratory of Boyuan Chen, professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at Duke.

“We wanted to create a solution that could work with complex and diverse objects found on a daily basis, giving robots a much richer ability to ‘feel’ and understand the world.”

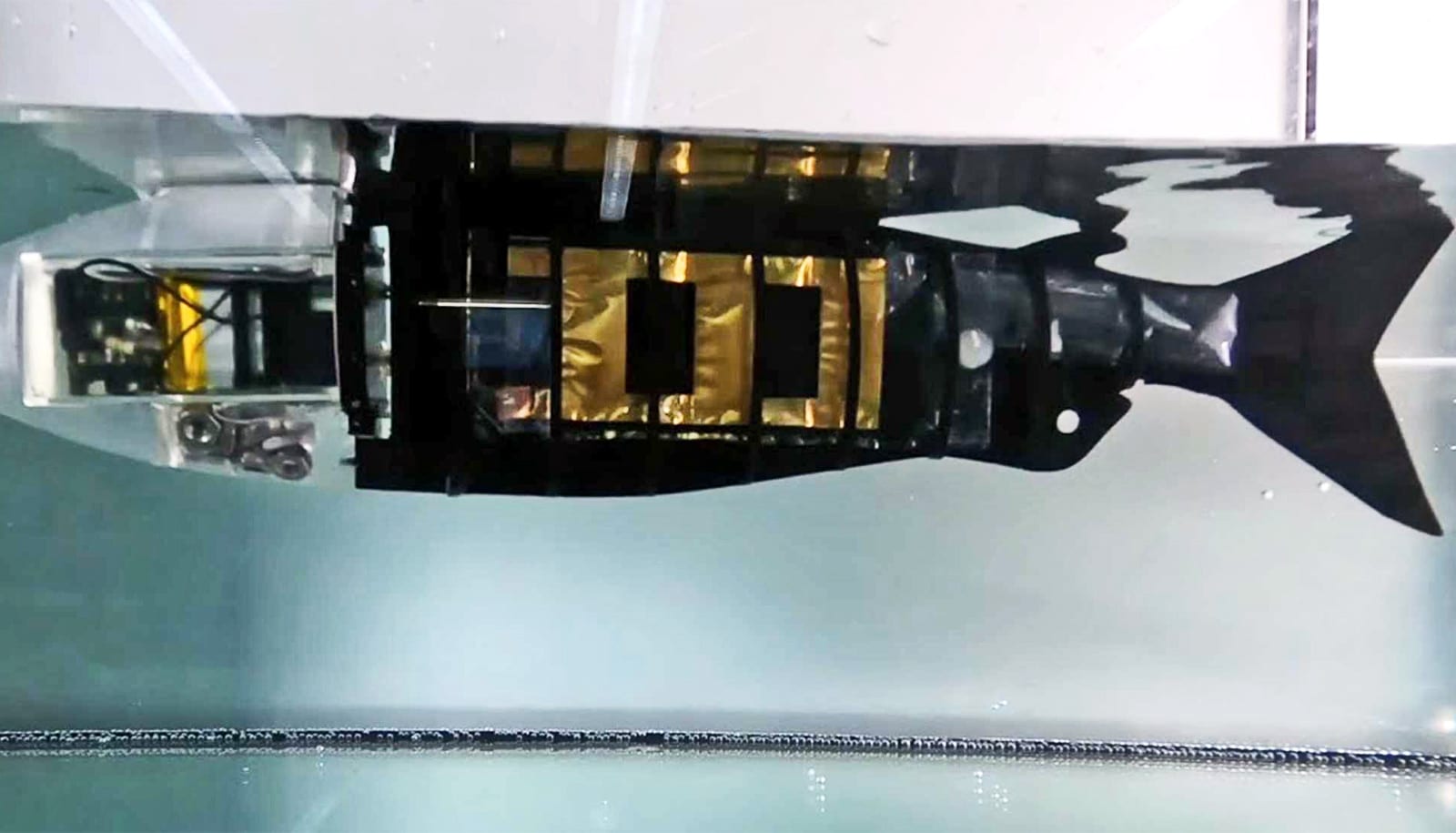

SonicSense features a robotic hand with four fingers, each equipped with a contact microphone embedded in the fingertip. These sensors detect and record vibrations generated when the robot taps, grasps, or shakes an object. And because the microphones are in contact with the object, it allows the robot to tune out ambient noises.

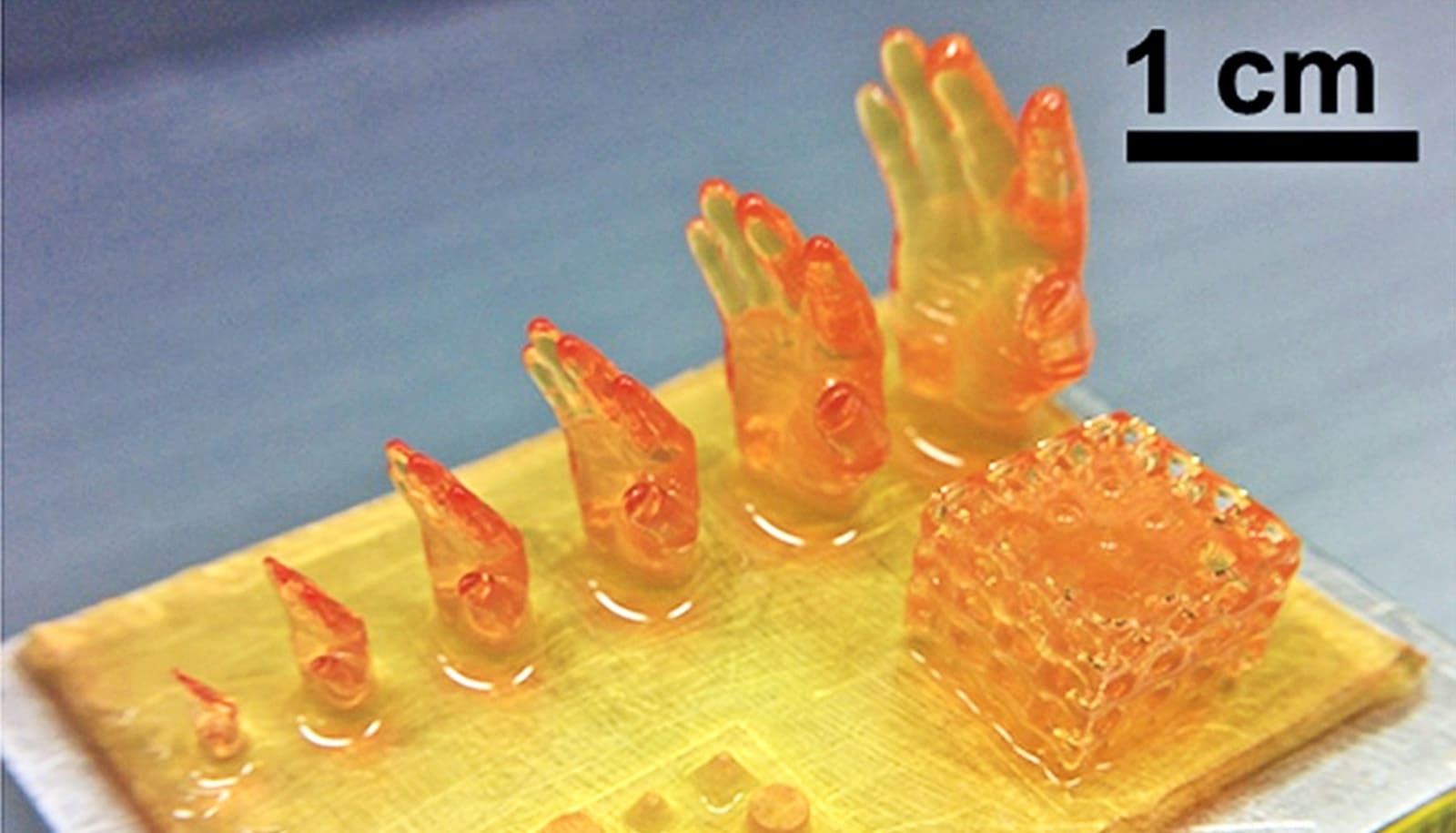

Based on the interactions and detected signals, SonicSense extracts frequency features and uses its previous knowledge, paired with recent advancements in AI, to figure out what material the object is made out of and its 3D shape. If it’s an object the system has never seen before, it might take 20 different interactions for the system to come to a conclusion. But if it’s an object already in its database, it can correctly identify it in as little as four.

“SonicSense gives robots a new way to hear and feel, much like humans, which can transform how current robots perceive and interact with objects,” says Chen, who also has appointments and students from electrical and computer engineering and computer science. “While vision is essential, sound adds layers of information that can reveal things the eye might miss.”

In the paper and demonstrations, Chen and his laboratory showcase a number of capabilities enabled by SonicSense. By turning or shaking a box filled with dice, it can count the number held within as well as their shape. By doing the same with a bottle of water, it can tell how much liquid is contained inside. And by tapping around the outside of an object, much like how humans explore objects in the dark, it can build a 3D reconstruction of the object’s shape and determine what material it’s made from.

While SonicSense is not the first attempt to use this approach, it goes further and performs better than previous work by using four fingers instead of one, touch-based microphones that tune out ambient noise and advanced AI techniques. This setup allows the system to identify objects composed of more than one material with complex geometries, transparent or reflective surfaces, and materials that are challenging for vision-based systems.

“While most datasets are collected in controlled lab settings or with human intervention, we needed our robot to interact with objects independently in an open lab environment,” says Liu. “It’s difficult to replicate that level of complexity in simulations. This gap between controlled and real-world data is critical, and SonicSense bridges that by enabling robots to interact directly with the diverse, messy realities of the physical world.”

Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering & Materials Science and Computer Science at Duke University

These abilities make SonicSense a robust foundation for training robots to perceive objects in dynamic, unstructured environments. So does its cost; using the same contact microphones that musicians use to record sound from guitars, 3D printing and other commercially available components keeps the construction costs to just over $200.

Moving forward, the group is working to enhance the system’s ability to interact with multiple objects. By integrating object-tracking algorithms, robots will be able to handle dynamic, cluttered environments — bringing them closer to human-like adaptability in real-world tasks.

Another key development lies in the design of the robot hand itself. “This is only the beginning. In the future, we envision SonicSense being used in more advanced robotic hands with dexterous manipulation skills, allowing robots to perform tasks that require a nuanced sense of touch,” Chen says. “We’re excited to explore how this technology can be further developed to integrate multiple sensory modalities, such as pressure and temperature, for even more complex interactions.”

Support for the work came from the Army Research laboratory STRONG program and DARPA’s FoundSci program and TIAMAT.

Source: Duke University