A new machine-knitted sweater “skin” could help robots sense contact and pressure.

“We can use that to make the robot smarter during its interaction with humans,” says Changliu Liu, an assistant professor of robotics in the school of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University.

Just as knitters can take any kind of yarn and turn it into a sock, hat, or sweater of any size or shape, the knitted RobotSweater fabric can be customized to fit uneven three-dimensional surfaces.

“Knitting machines can pattern yarn into shapes that are non-flat, that can be curved or lumpy,” says James McCann, an assistant professor in the school of computer science whose research has focused on textile fabrication in recent years. “That made us think maybe we could make sensors that fit over curved or lumpy robots.”

Once knitted, the fabric can be used to help the robot “feel” when a human touches it, particularly in an industrial setting where safety is paramount. Current solutions for detecting human-robot interaction in industry look like shields and use very rigid materials that Liu notes can’t cover the robot’s entire body because some parts need to deform.

“With RobotSweater, the robot’s whole body can be covered, so it can detect any possible collisions,” says Liu, whose research focuses on industrial applications of robotics.

RobotSweater’s knitted fabric consists of two layers of conductive yarn made with metallic fibers to conduct electricity. Sandwiched between the two is a net-like, lace-patterned layer. When pressure is applied to the fabric—say, from someone touching it—the conductive yarn closes a circuit and is read by the sensors.

“The force pushes together the rows and columns to close the connection,” says Wenzhen Yuan, an assistant professor school of computer science and director of the RoboTouch lab. “If there’s a force through the conductive stripes, the layers would contact each other through the holes.”

Apart from how to design the knitted layers, including dozens if not hundreds of samples and tests, the team faced another challenge in connecting the wiring and electronics components to the soft textile.

“There was a lot of fiddly physical prototyping and adjustment,” McCann says. “The students working on this managed to go from something that seemed promising to something that actually worked.”

What worked was wrapping the wires around snaps attached to the ends of each stripe in the knitted fabric. Snaps are a cost-effective and efficient solution, such that even hobbyists creating textiles with electronic elements, known as e-textiles, could use them, McCann says.

“You need a way of attaching these things together that is strong, so it can deal with stretching, but isn’t going to destroy the yarn,” he says, adding that the team also discussed using flexible circuit boards.

Once fitted to the robot’s body, RobotSweater can sense the distribution, shape, and force of the contact. It’s also more accurate and effective than the visual sensors most robots rely on now.

“The robot will move in the way that the human pushes it, or can respond to human social gestures,” Yuan says.

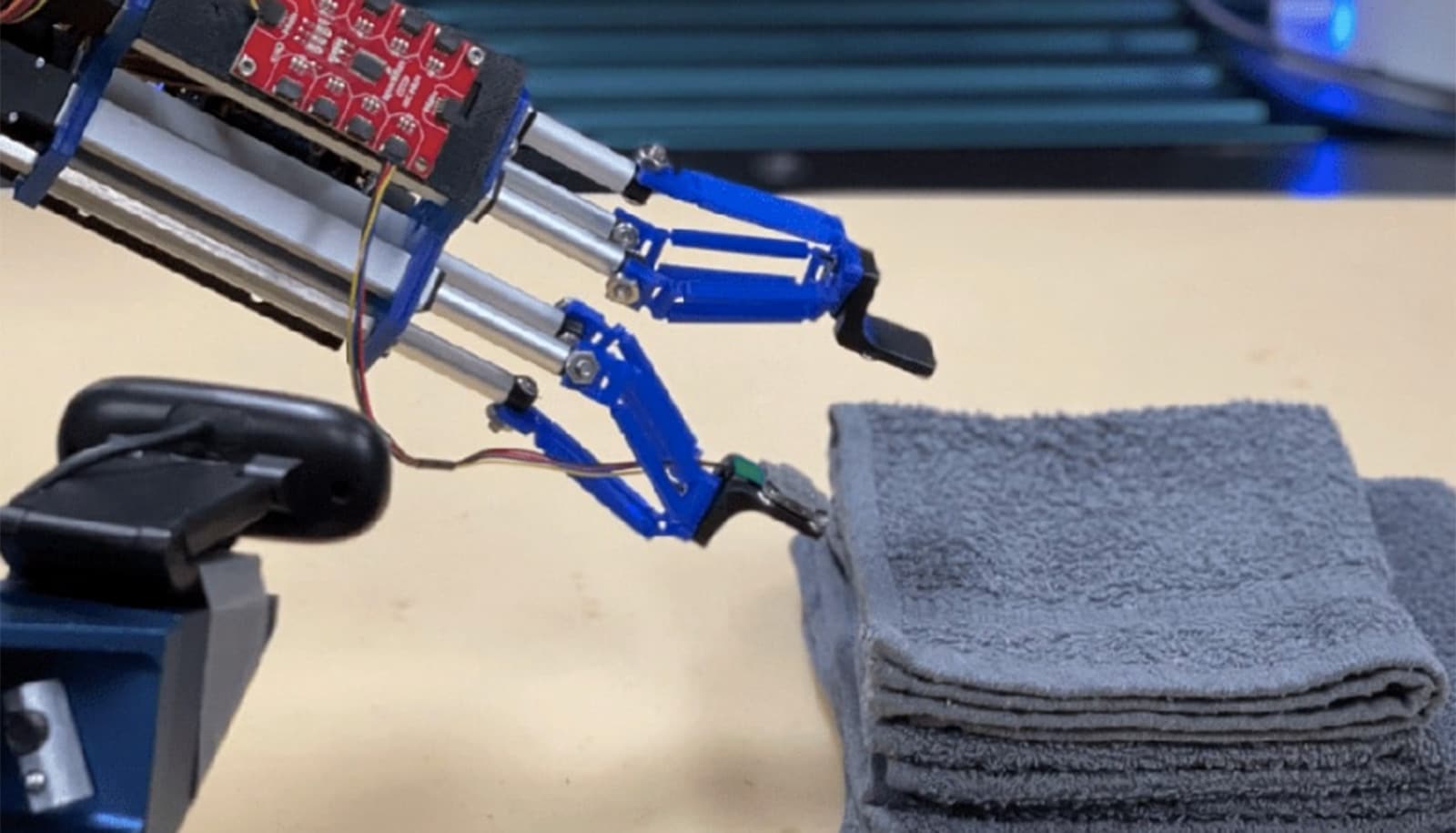

In the research, the team demonstrated that pushing on a companion robot outfitted in RobotSweater told it which way to move or what direction to turn its head. When used on a robot arm, RobotSweater allowed a push from a person’s hand to guide the arm’s movement, while grabbing the arm told it to open or close its gripper.

In future research, the team wants to explore how to program reactions from the swipe or pinching motions used on a touchscreen.

The researchers will present the RobotSweater research paper, currently in preprint, at the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). Additional coauthors are from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Carnegie Mellon.

Source: Carnegie Mellon University