Researchers have achieved a significant milestone in their work to create a biomaterial that can be used to grow biological tissues outside the human body.

The development of a new fabrication process to create aligned nanofiber hydrogels could offer new possibilities for tissue regeneration after injury and provide a way to test therapeutic drug candidates without the use of animals.

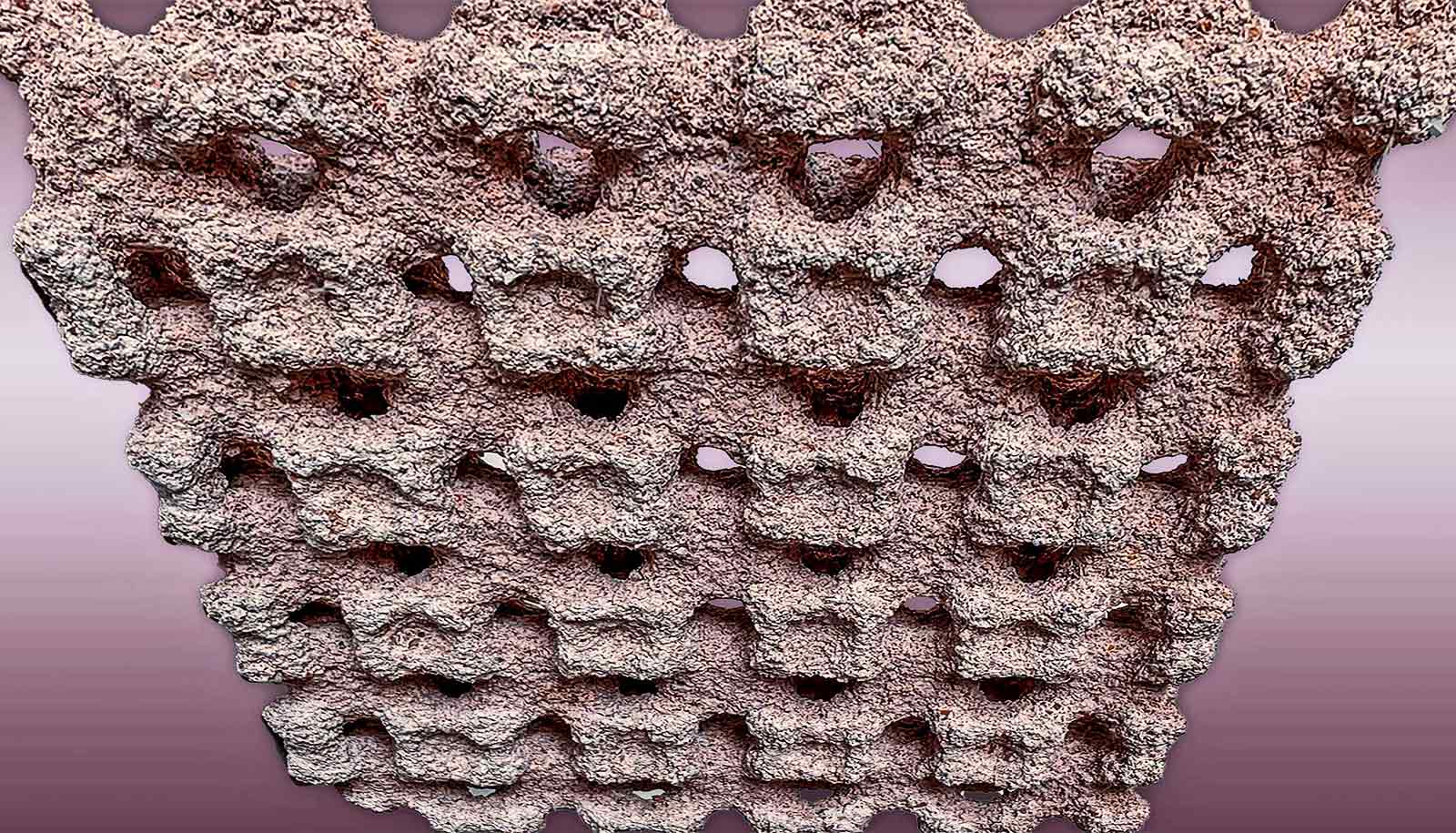

Jeffrey Hartgerink, professor of chemistry and bioengineering at Rice University and colleagues, developed peptide-based hydrogels that mimic the aligned structure of muscle and nerve tissues. Alignment is critical for the tissues’ functionality, but it is a challenging feature to reproduce in the lab, as it entails lining up individual cells.

For over 10 years, the team has been designing multidomain peptides (MDPs) that self-assemble into nanofibers. These resemble the fibrous proteins found naturally in the body, much like a spiderweb at nanoscale.

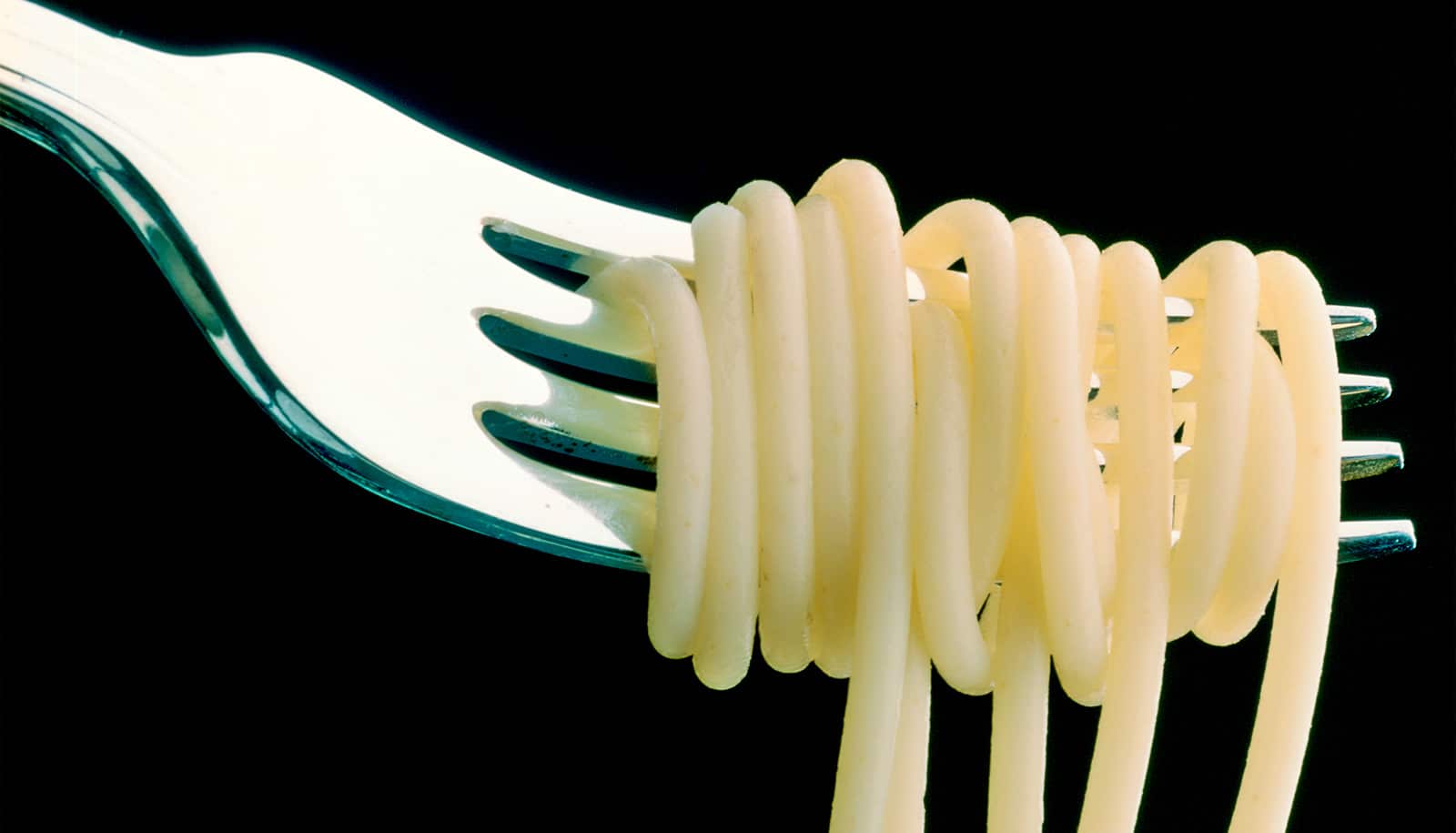

In their latest study, published in the journal ACS Nano, the researchers discovered a new method to create aligned MDP nanofiber “noodles.” By first dissolving the peptides in water and then extruding them into a salty solution, they were able to create aligned peptide nanofibers—like twisted strands of rope smaller than a cell. By increasing the concentration of ions, or salt, in the solution and repeating the process, they achieved even greater alignment of the nanofibers.

“Our findings demonstrate that our method can produce aligned peptide nanofibers that effectively guide cell growth in a desired direction,” explains lead author Adam Farsheed, who recently received his PhD in bioengineering from Rice. “This is a crucial step toward creating functional biological tissues for regenerative medicine applications.”

One of the key findings of the study was an unexpected discovery: When the alignment of the peptide nanofibers was too strong, the cells no longer aligned. Further investigation revealed that the cells needed to be able to “pull” on the peptide nanofibers to recognize the alignment.

When the nanofibers were too rigid, the cells were unable to exert this force and failed to arrange themselves in the desired configuration.

“This insight into cell behavior could have broader implications for tissue engineering and biomaterial design,” says Hartgerink. “Understanding how cells interact with these materials at the nanoscale could lead to more effective strategies for building tissues.”

Additional coauthors are from Rice and the University of Houston.

The National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Welch Foundation supported the work. The content in this news release is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations.

Source: Rice University