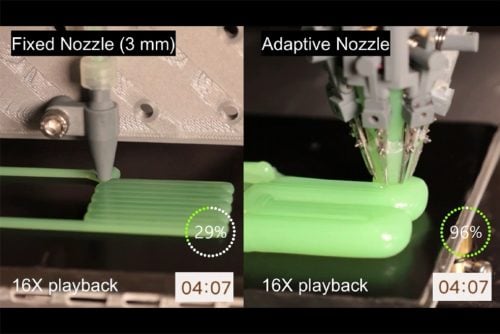

A new 3D printing technique uses a nozzle that can change its size and shape during the printing process.

The new nozzle overcomes the speed-resolution tradeoff inherent to traditional 3D printers with fixed-nozzle diameters.

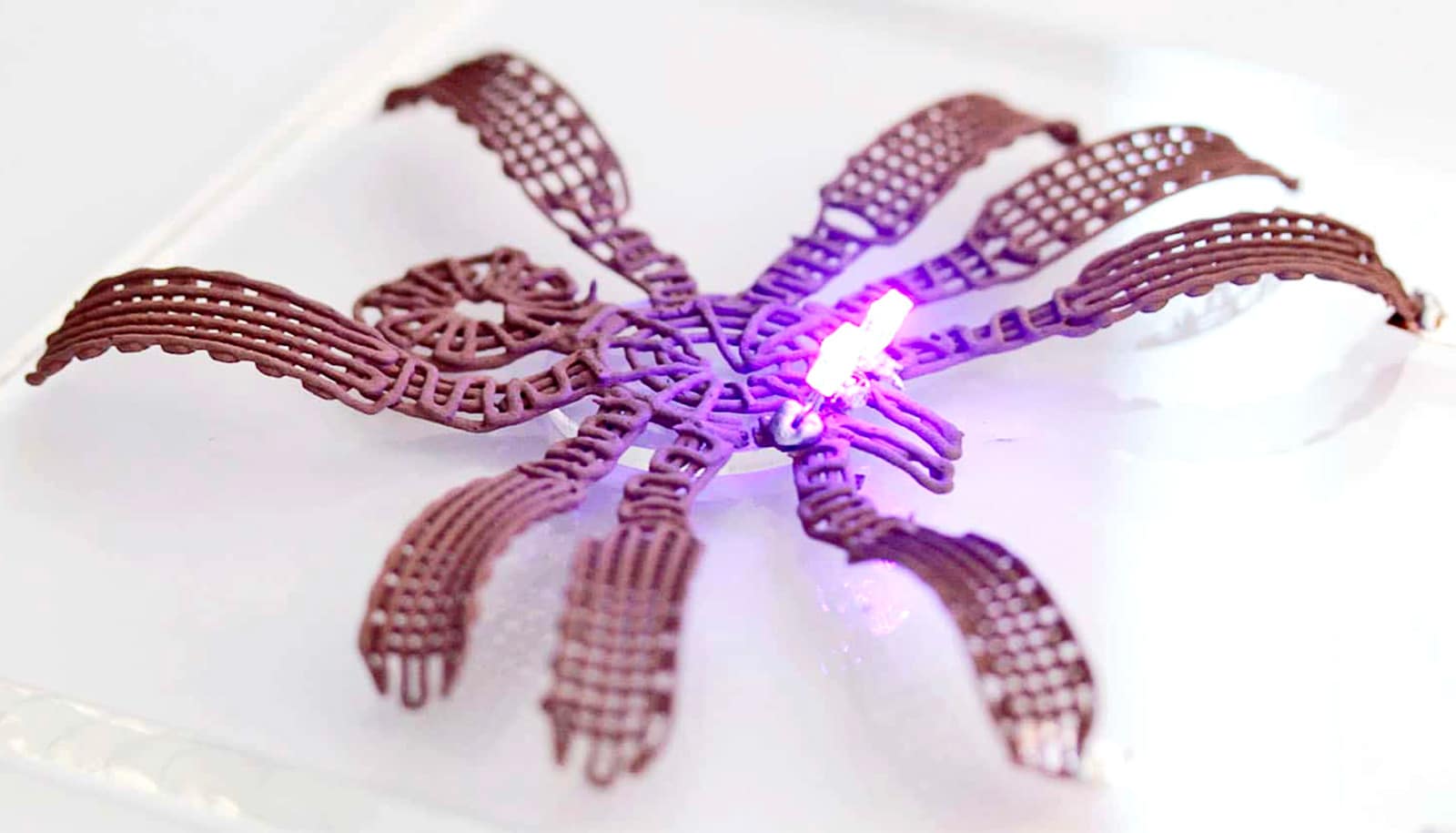

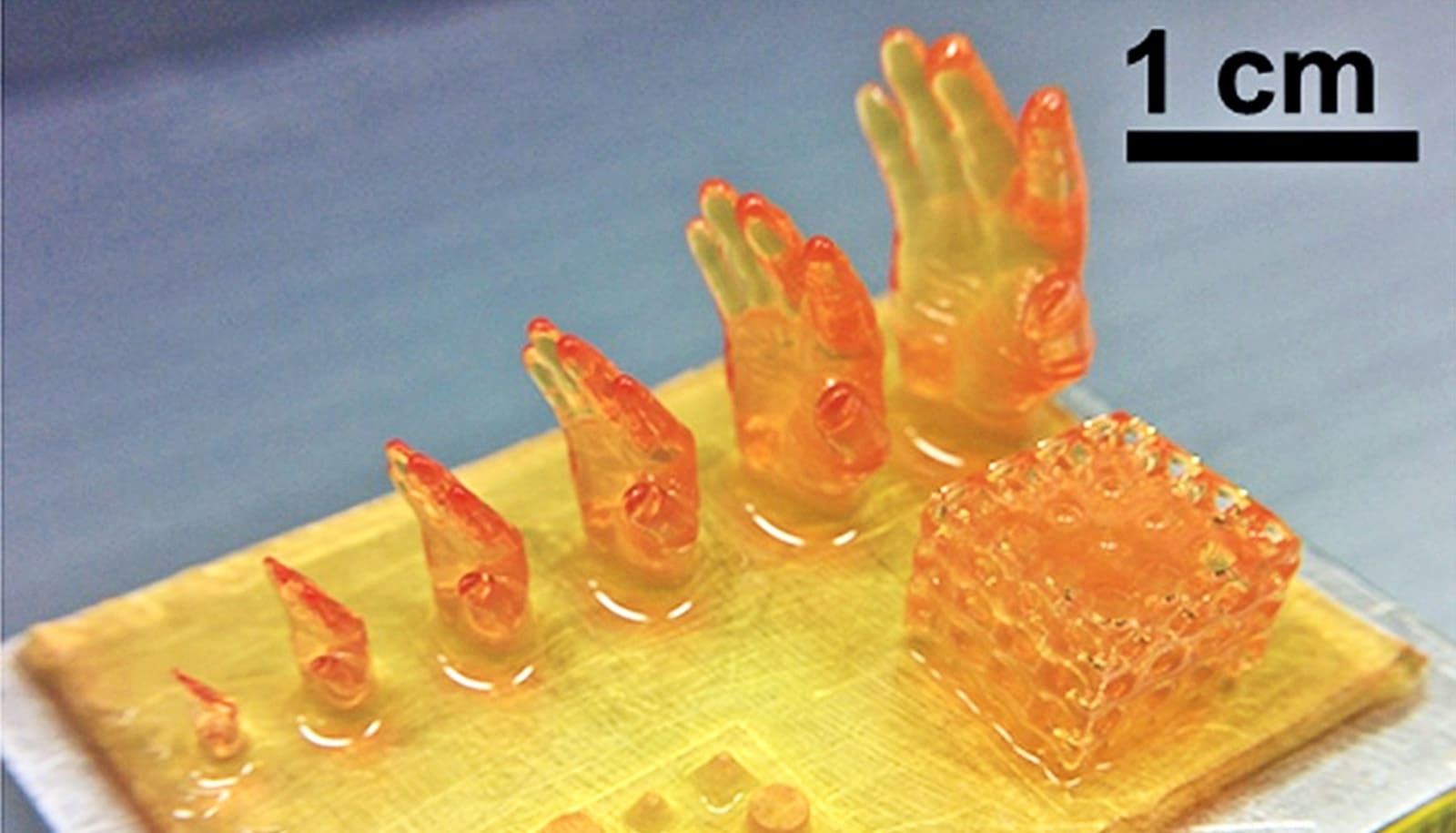

The researchers say that the new nozzle, also known as AN3DP, promises to improve the printing of everything from aerospace components and soft electronic devices to structural beams and walls.

The team’s work appears in Science Advances.

“Traditional 3D printers use fixed nozzles, which limit either resolution or speed. Smaller nozzles improve resolution but slow down printing, while larger nozzles increase speed but reduce detail. AN3DP’s design overcomes this by adjusting to the specific requirements of each feature being printed, allowing for both high resolution and faster printing,” says corresponding author Jochen Mueller, assistant professor in the Whiting School of Engineering’s civil and systems engineering department, who worked with Seok Won Kang, a postdoctoral fellow, on the project.

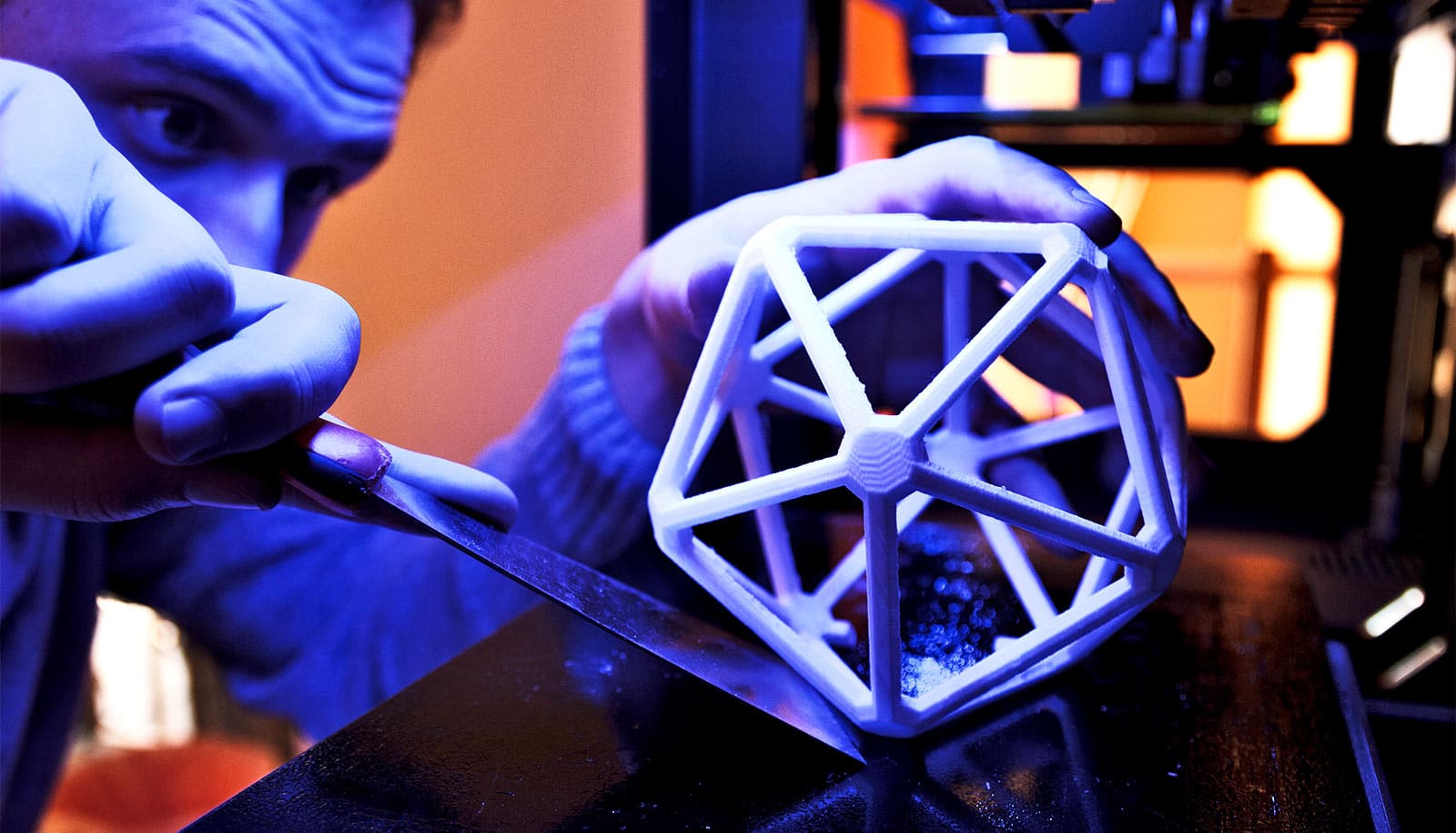

Inspired by the mechanisms of retractable grabber tools and tendons in humans and animals, AN3DP uses eight movable pins controlled by motors to change its shape and size. Connecting the pins is an elastic membrane that allows the material emerging from the nozzle to maintain a smooth shape. The movable pins and elastic membrane together allow for the accurate production of highly complex structures, the engineers say.

“One of the major benefits of this adaptive nozzle is its ability to reduce the ‘stair-stepping’ effect, which is common in traditional 3D printing,” says Mueller.

“This effect, reminiscent of the blocky figures in the popular game Minecraft, occurs when sloped or curved surfaces are printed using fixed nozzle sizes, resulting in a series of small, visible steps rather than a smooth surface. By adjusting the nozzle shape and size during the printing process, we can create smoother, continuous surfaces, enhancing the overall quality of printed objects.”

While AN3DP solves two primary challenges in 3D printing—accuracy and speed—it has shortcomings of its own, the team says. For instance, the current nozzle design requires manual assembly and cleaning and can only be used for a single type of fabrication process.

Mueller and Kang plan to address these limitations by refining the design to make it more practical for widespread use. They also aim to adapt AN3DP for Fused Filament Fabrication, a common 3D printing process, which would broaden its application to include more every day and industrial uses.

“I’m really excited about AN3DP and its future applications. Its flexibility is going to improve the structural integrity and functionality of printed objects, making them more suitable for complex engineering applications,” says Mueller.

Source: Johns Hopkins University