Biologists have captured a caecilian, an obscure legless amphibian native to Colombia and Venezuela, in Miami.

It’s the first example of an introduced caecilian in the United States.

Scientists from the Florida Museum of Natural History used DNA testing to identify the specimen as the Rio Cauca caecilian, Typhlonectes natans.

While caecilians—pronounced like “Sicilians”—hunt and scavenge various kinds of small animals, museum experts say it’s too early to predict their potential impact on the local ecosystem.

“Very little is known about these animals in the wild, but there’s nothing particularly dangerous about them, and they don’t appear to be serious predators,” says Coleman Sheehy, Florida Museum’s herpetology collection manager.

“They’ll probably eat small animals and get eaten by larger ones. This could be just another non-native species in the South Florida mix.”

Sheehy first learned of the caecilian when officers from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission sent him a photograph in 2019, puzzled at the two-foot-long eel-like animal they had netted in shallow water during a routine survey of the Tamiami Canal, also known as the C-4 Canal.

After the caecilian died in captivity, it was sent to the Florida Museum for further analysis. Since then, Sheehy has received several other specimens and reports of caecilians in the canal and will conduct fieldwork in the area to determine their numbers and range.

“At this point, we really don’t know enough to say whether caecilians are established in the C-4 Canal,” he says. “That’s what we want to find out.”

Caecilian sizes

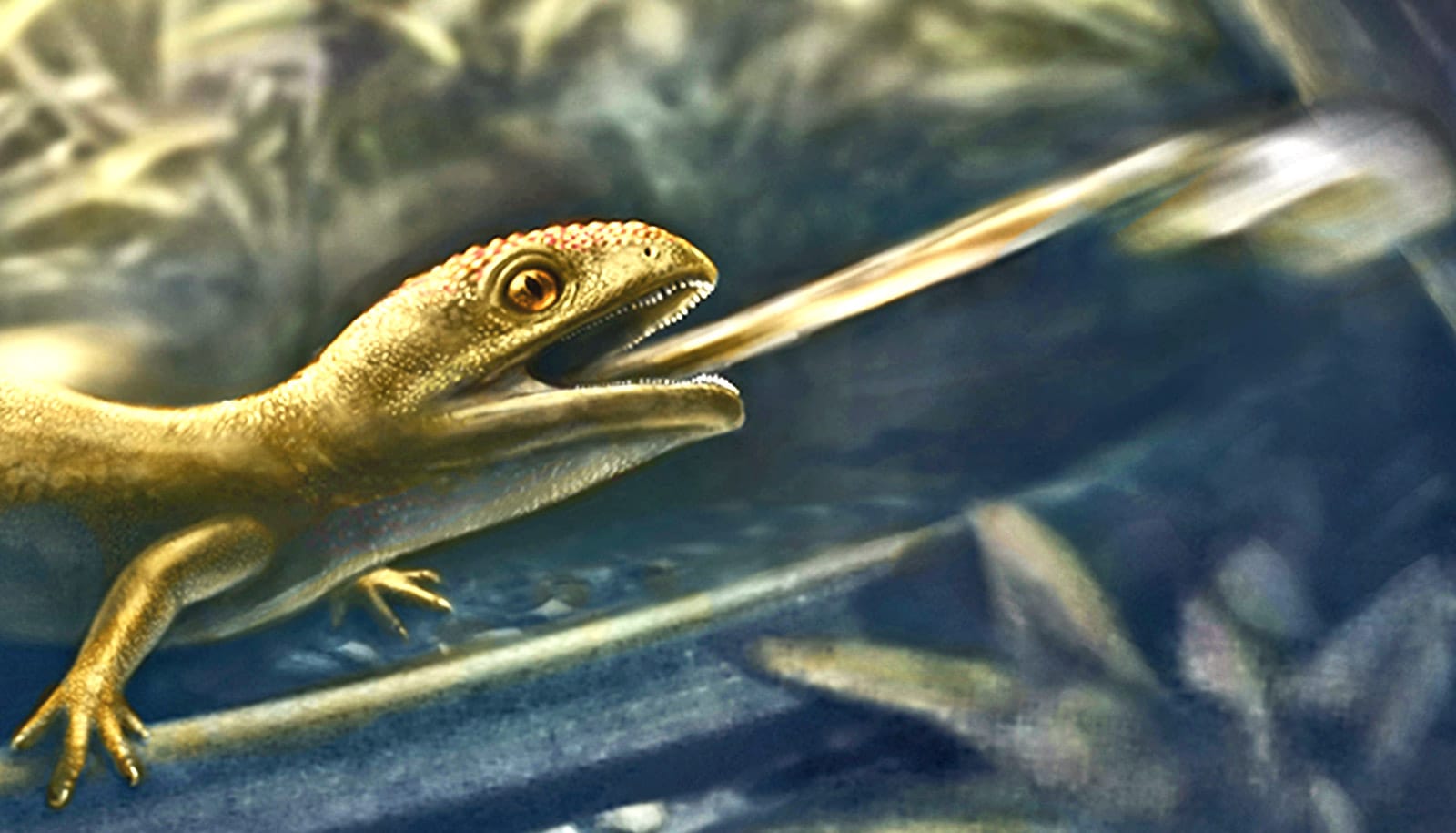

Little is known about this group of reclusive animals. Many caecilians spend their lives burrowed underground while others, including Typhlonectes natans, exclusively inhabit fresh water.

Although they resemble worms or snakes, they comprise a separate order of amphibians, distinct from frogs, toads, salamanders, and newts. Caecilians can range in size from a few inches to 5 feet long, depending on the species, and have extremely poor eyesight—their name translates to “blind ones.” They also have a pair of sensory tentacles located between their eyes and nostrils, structures that are unique to caecilians and may help them find food.

The northern tip of their range in the Western Hemisphere is southern Mexico, which is home to a group of land-dwelling caecilians, and they’re also found in tropical parts of Africa and Southeast Asia. Fossil remains of ancient caecilian ancestors, dating back more than 170 million years, have been discovered in the American Southwest, but apart from the caecilians recently introduced to South Florida, no representatives of this lineage live in the US today.

“This was not on my radar,” Sheehy says. “I didn’t think we’d one day find a caecilian in Florida. So, this was a huge surprise.”

Abandoned pets?

Typhlonectes natans is the most common caecilian in the pet trade and will breed in captivity, giving birth to live young. Because this species is generally kept in aquariums indoors and can’t easily escape, Sheehy suspects someone discarded their unwanted pets in the canal.

In its native range, Typhlonectes natans lives in warm, slow-moving bodies of shallow water with aquatic vegetation.

“Parts of the C-4 Canal are just like that,” Sheehy says. “This may be an environment where this species can thrive.”

The paper appears in the journal Reptiles & Amphibians. Additional coauthors are from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and the Florida Museum.

Source: University of Florida