Fossils of bizarre, armored amphibians known as albanerpetontids provide the oldest evidence of a slingshot-style tongue, a new study shows.

Despite having lizardlike claws, scales, and tails, albanerpetontids—mercifully called “albies” for short—were amphibians, not reptiles.

Their lineage was distinct from today’s frogs, salamanders, and caecilians and dates back at least 165 million years, dying out only about 2 million years ago.

“This discovery adds a super-cool piece to the puzzle of this obscure group of weird little animals.”

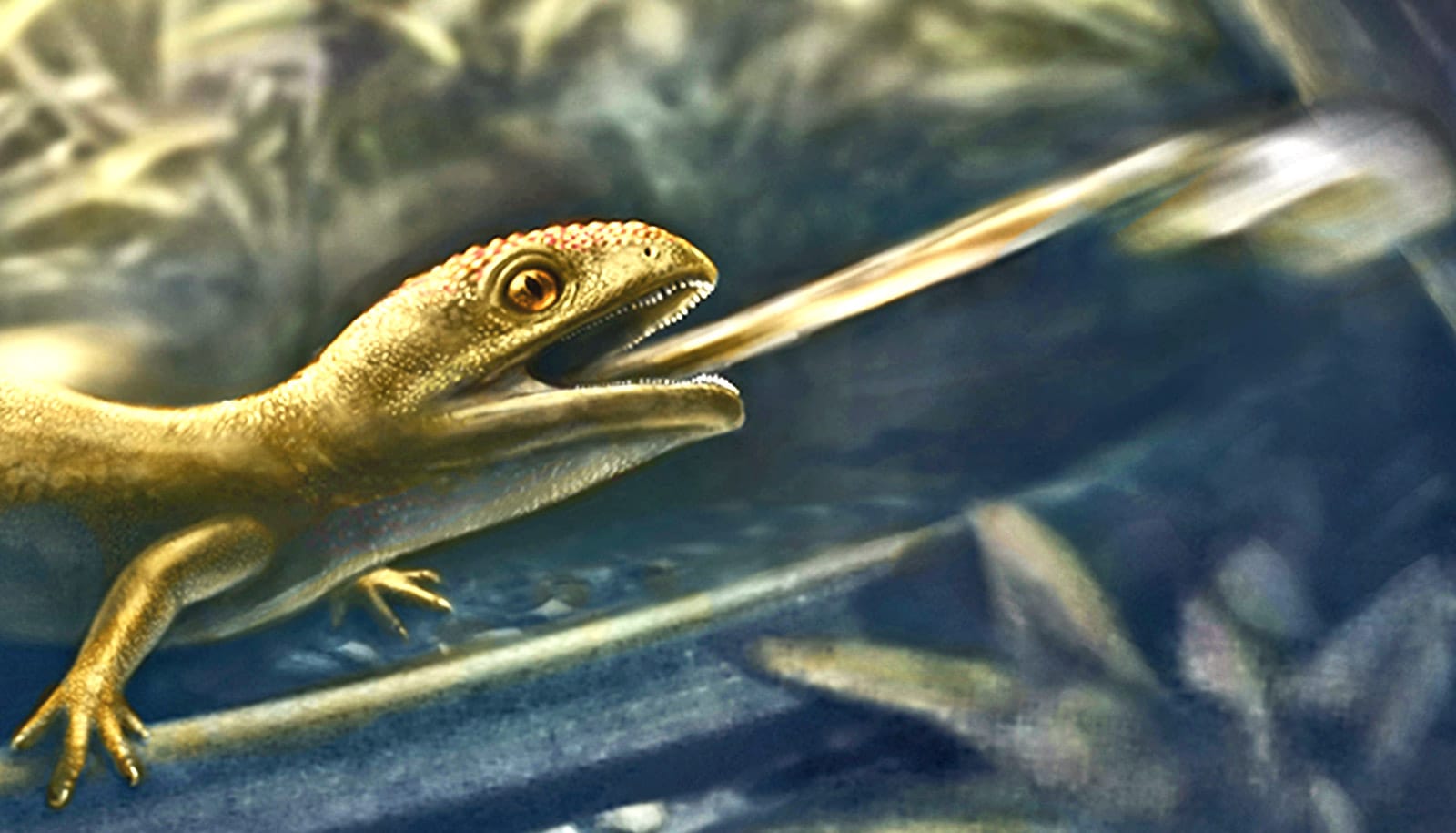

Now, a set of 99-million-year-old fossils redefines these tiny animals as sit-and-wait predators that snatched prey with a projectile firing of their tongue—and not underground burrowers, as once thought. The fossils, one previously misidentified as an early chameleon, are the first albies discovered in modern-day Myanmar and the only known examples in amber.

They also represent a new genus and species: Yaksha perettii, named after treasure-guarding spirits known as yakshas in Hindu literature and Adolf Peretti, the discoverer of two of the fossils.

“This discovery adds a super-cool piece to the puzzle of this obscure group of weird little animals,” says coauthor Edward Stanley, director of the Florida Museum of Natural History’s Digital Discovery and Dissemination Laboratory.

“Knowing they had this ballistic tongue gives us a whole new understanding of this entire lineage,” Stanley says.

‘One of the worst days of my life’

The discovery began with a bumble.

In 2016, Stanley and Juan Diego Daza, lead author of the study and assistant professor of biological sciences at Sam Houston State University, published a paper presenting a dozen rare amber fossil lizards—or so they thought. One juvenile specimen possessed a hodgepodge of bewildering characteristics, including a specialized tongue bone.

After much debate and consultation with colleagues, the scientists finally labeled it an ancient chameleon, about 99 million years old, an estimate based on radiometric dating of crystals at the site where the fossil was found.

“We envision this as a stocky little thing scampering in the leaf litter, well hidden, but occasionally coming out for a fly…”

When she read the study, Susan Evans, professor of vertebrate morphology and paleontology at University College London and an albie expert, instantly recognized the puzzling specimen. It was no chameleon. She emailed Daza.

“I remember that as one of the worst days of my life,” he says.

But the paper also attracted the attention of an unexpected collaborator: Peretti, a gemologist who contacted Daza about another collection of amber fossil lizards from the same region of Myanmar. (Note: The mining and sale of Burmese amber are often entangled with human rights abuses. Peretti acquired the fossils legally from companies that follow a strict ethical code. More details appear in an ethics statement at the end of this post).

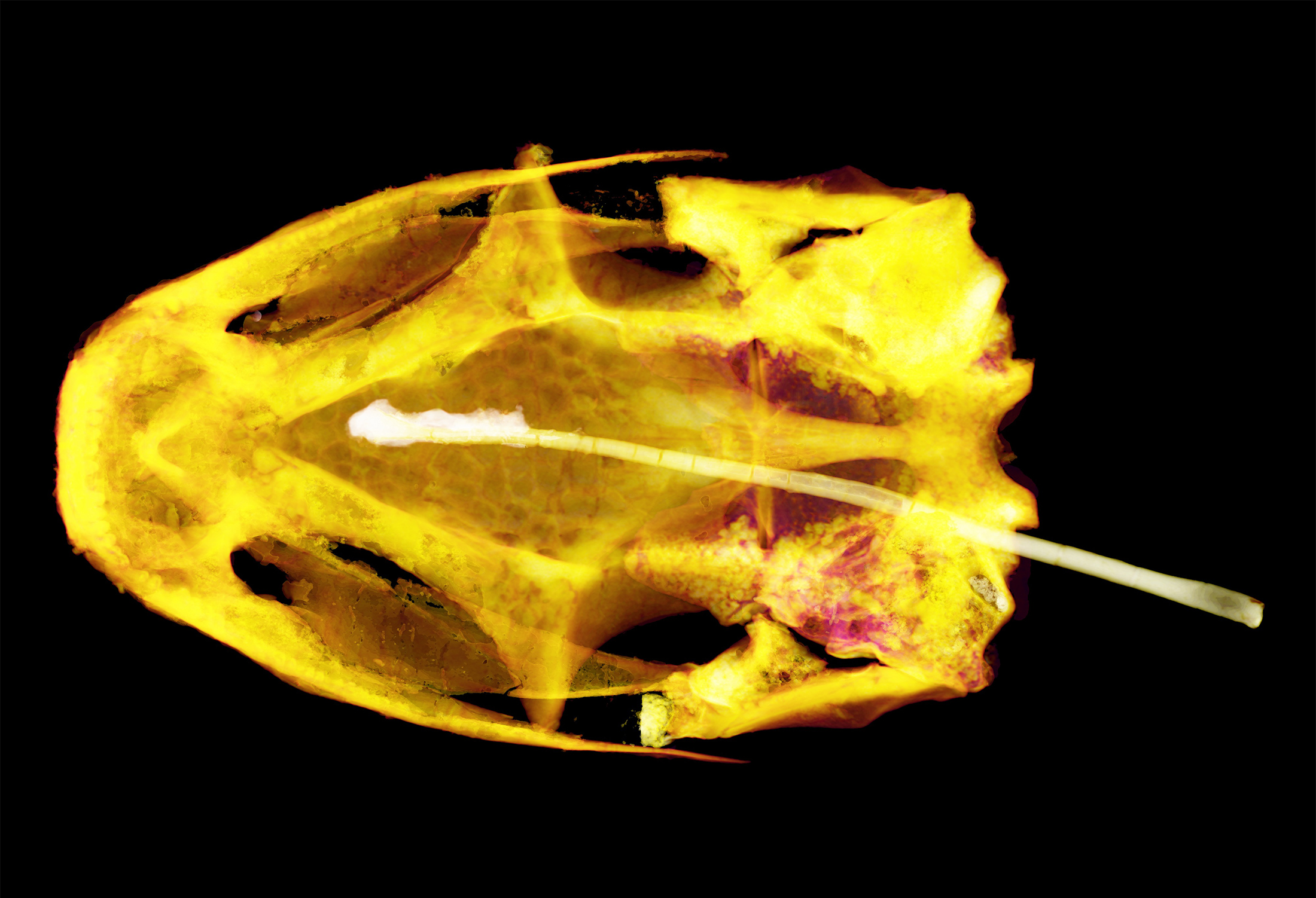

Per Daza’s recommendation, Peretti sent the collection to the University of Texas at Austin for CT scanning, a way of clarifying what lies inside. As Daza began cleaning up the scans, one fossil in particular caught his eye—the complete skull of an adult albie.

Most fossil albies are crushed flat or a jumble of bones in disarray. In 1995, Evans published the first description of a complete specimen, excavated in Spain, but “it was very much roadkill,” she says. Even amber fossils suffer degradation, and soft tissues can mineralize, becoming difficult to work with.

This specimen, however, was not only three-dimensional, “it was in mint condition,” Stanley says. “Everything was where it was supposed to be. There was even some soft tissue,” including the tongue pad and parts of the jaw muscles and eyelids.

It was also the adult counterpart to the juvenile albie that had been mistaken for a chameleon.

When Daza sent the scan to Evans, she was dazzled by its rich detail.

“All my Christmases have come at once!” she wrote back.

The ‘weird and wonderful’ albies

Once classified as salamanders, albies’ stippled, reinforced skulls led many scientists to hypothesize they were diggers. No one imagined them as having chameleonlike lifestyles, Stanley says. But, he adds, “if you’re going to misidentify an albie as any kind of lizard, a chameleon is absolutely what you would land on.”

Even though one is an amphibian and the other a reptile, they share several features, including claws, scales, massive eye sockets, and—we now know—a projectile feeding mechanism.

The chameleon tongue is one of the fastest muscles in the animal kingdom and can rocket from 0 to 60 mph in a hundredth of a second in some species. It gets its speed from a specialized accelerator muscle that stores energy by contracting and then launching the elastic tongue with a recoil effect.

If the earliest albies also had ballistic tongues, the feature is much older than the first chameleons, which may have appeared 120 million years ago. Fossil evidence indicates albies are at least 165 million years old, though Evans says their lineage must be much more ancient, originating more than 250 million years ago.

While armed with a rapid-fire tongue, Y. perettii was tiny: Based on the fossil skull, Daza estimates the adult was about 2 inches long, not including the tail. The juvenile was a quarter that size.

“We envision this as a stocky little thing scampering in the leaf litter, well hidden, but occasionally coming out for a fly, throwing out its tongue, and grabbing it,” Evans says.

The revelation that albies had projectile tongues helps explain some of their “weird and wonderful” features, such as unusual jaw and neck joints and large, forward-looking eyes, a common characteristic of predators, she says. They may also have breathed through their skin, as salamanders do.

Even though the specimens are remarkably preserved, Stanley says CT scanning was essential to the analysis, revealing fine-scale features obscured in the cloudy amber.

“They only come to life with CT scanning,” he says. “Digital technology is really key with this amber material.”

Digitization also enabled the researchers, scattered around the world and hunkered down during COVID-19 quarantines, to collaboratively analyze and describe the specimens—and then make the same material digitally available to others.

Where do albanerpetontids fit?

Despite the level of preservation and completeness of the Y. perettii specimens, albies’ exact place in the amphibian family tree remains a mystery. The researchers coded the specimens’ physical characteristics and ran them through four models of amphibian relationships with no clear results. The animals’ unusual combination of features is likely to blame, Evans says.

“In theory, albies could give us a clue as to what the ancestors of modern amphibians looked like,” she says. “Unfortunately, they’re so specialized and so weird in their own way that they’re not helping us all that much.”

But Y. perettii does put albies on a new part of the map. Northwest Myanmar was likely an island 99 million years ago and possibly a remnant from Gondwana, the ancient southern continental landmass. With two exceptions in Morocco, all other fossil albies have been found in North America, Europe, and East Asia, which formerly formed a northern continental landmass. Daza says Y. perettii may have rafted to the island from mainland Asia or could represent a new southern record for the group.

With such a wide distribution, why did albies vanish into extinction while frogs, salamanders, and caecilians still exist today?

We don’t know. Albies almost survived to the present, fading out about 2 million years ago, possibly late enough to have crossed paths with our earliest hominid relatives, Evans says.

“We only just missed them. I keep hoping they’re still alive somewhere.”

3D digitized specimens are available online via MorphoSource. The adult skull is housed at the Peretti Museum Foundation in Switzerland, and the juvenile specimen is at the American Museum of Natural History.

The research appears in Science.

Additional study coauthors are from the Institut Català de Paleontologia; the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in Spain; the University of Bristol; Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET); Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia; the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation; and Allwetterzoo Münster in Germany.

Specimens were acquired following the ethical guidelines for the use of Burmese amber set forth by the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology. Peretti’s specimens were purchased from authorized companies that export amber pieces legally from Myanmar, following an ethical code that ensures no violations of human rights were committed during mining and commercialization and that money derived from sales did not support armed conflict. The fossils have an authenticated paper trail, including export permits from Myanmar. All documentation is available from the Peretti Museum Foundation upon request.

Funding came from the US National Science Foundation; Sam Houston State University; the Royal Society; the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities; the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya; the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic; and the Slovak Academy of Sciences.

Source: University of Florida