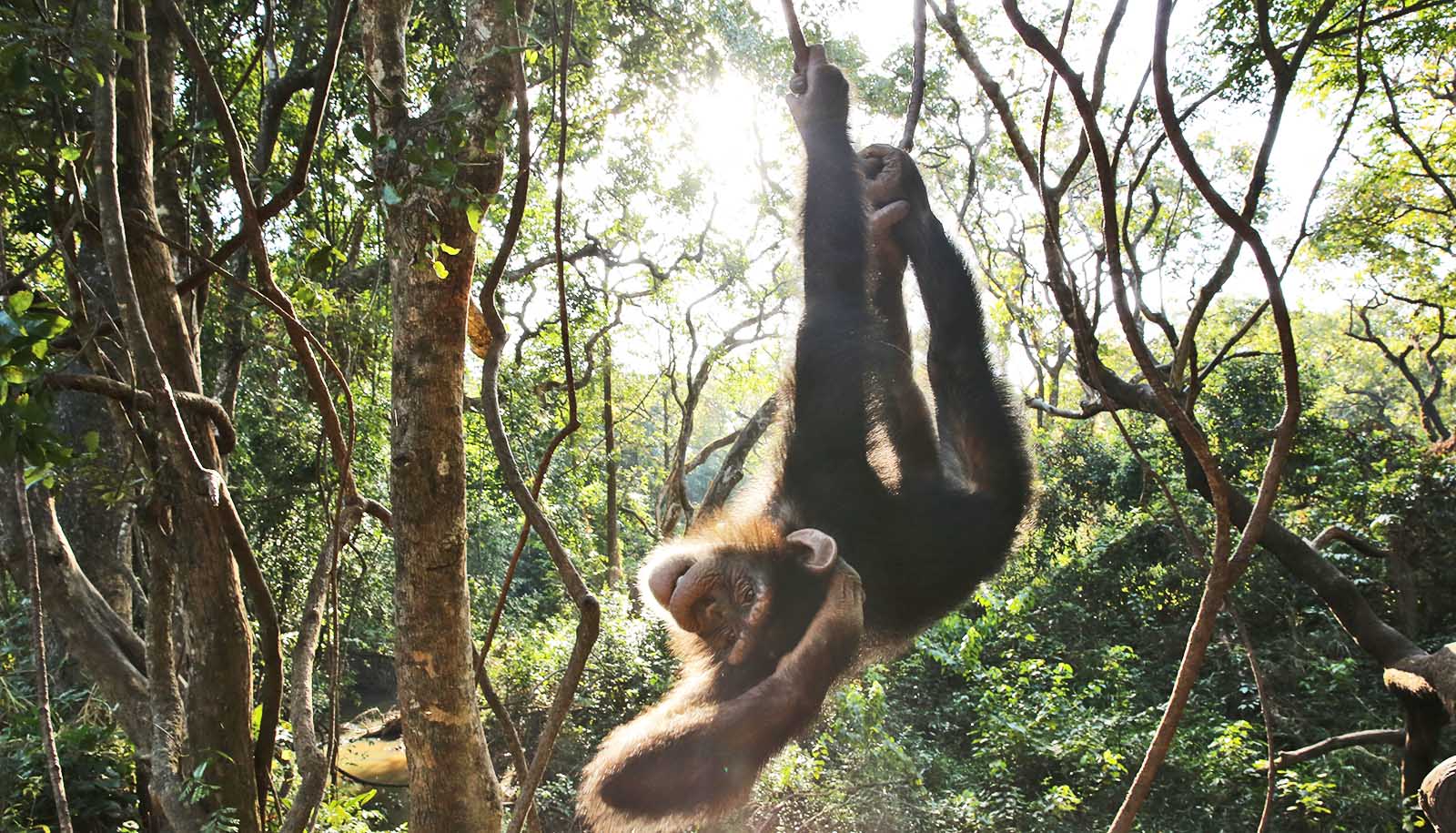

Researchers are using genetic information from western chimpanzees in Guinea to evaluate the effects of mining on the endangered species.

The western chimpanzee is listed as “critically endangered” on the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. The Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage site, located on the borders of Guinea, Liberia, and Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa, harbors a unique population of this subspecies.

However, this region is now under threat from mining activities immediately abutting its borders. Guinea is rich in minerals with some of the highest grade iron ore deposits in the world. “It is therefore crucial to establish tools to monitor this endangered chimpanzee population and assess the potential impact of mining,” says Kathelijne Koops, professor in the department of evolutionary anthropology at the University of Zurich.

To this end, Koops and her colleagues used genetic censusing to estimate chimpanzee population size, community composition, and range boundaries on the western flank of the massif in Guinea.

“Our study is the first to employ genetics on such a large scale to estimate the number and population structure of a critically endangered chimpanzee population in West Africa,” says Koops. During field work the researchers collected almost a thousand fecal samples of chimpanzees between 2003 and 2018. They analyzed the genetic material contained in these samples using a panel of 26 microsatellites—short pieces of DNA that allow the identification of individual animals as well as relatedness between them.

The analysis identified a total of 136 chimpanzees living in four different communities or social groups. The actual number of chimpanzees in the area probably significantly exceeds this minimum estimate. “Infants and juveniles are not reliably included in fecal sampling and some areas of the mountain range remain under-sampled”, says Christina Hvilsom, conservation geneticist at Copenhagen Zoo.

The team also found a number of migratory events, as well as high levels of shared ancestry and genetic diversity. “These findings highlight the utility of genetic censusing for temporal monitoring of ape abundance, as well as capturing migratory events, and gauging genetic diversity and population viability over time,” adds coauthor Peter Frandsen, also at Copenhagen Zoo. For example, the data allow predictions to be made as to how road building and extraction activities might affect chimpanzee movement between the different communities or reduce access to food and nesting sites.

“This study undeniably confirms the status of the Nimba UNESCO World Heritage Site as a priority site for the conservation of the critically endangered western chimpanzee,” says coauthor Dr. Tatyana Humle, senior associate at Re:wild. “It also demonstrates the value of employing non-invasive genetic techniques to generate critical data on population abundance, structure and genetic health.”

Koops adds: “For future impact assessments, we recommend genetic sampling, combined with camera trapping, as these methods can provide robust baselines for biomonitoring and conservation management,” not only for the western chimpanzee but also for other species of endangered great apes.

The team includes researchers from the University of Zurich, the University of Kent, Copenhagen Zoo, the University of Copenhagen, Texas A&M, and the Environmental Research Institute of Bossou in Guinea. The paper appears in the journal Conservation Science and Practice.

Source: University of Zurich