Voting by mail doesn’t benefit one political party over the other, researchers report.

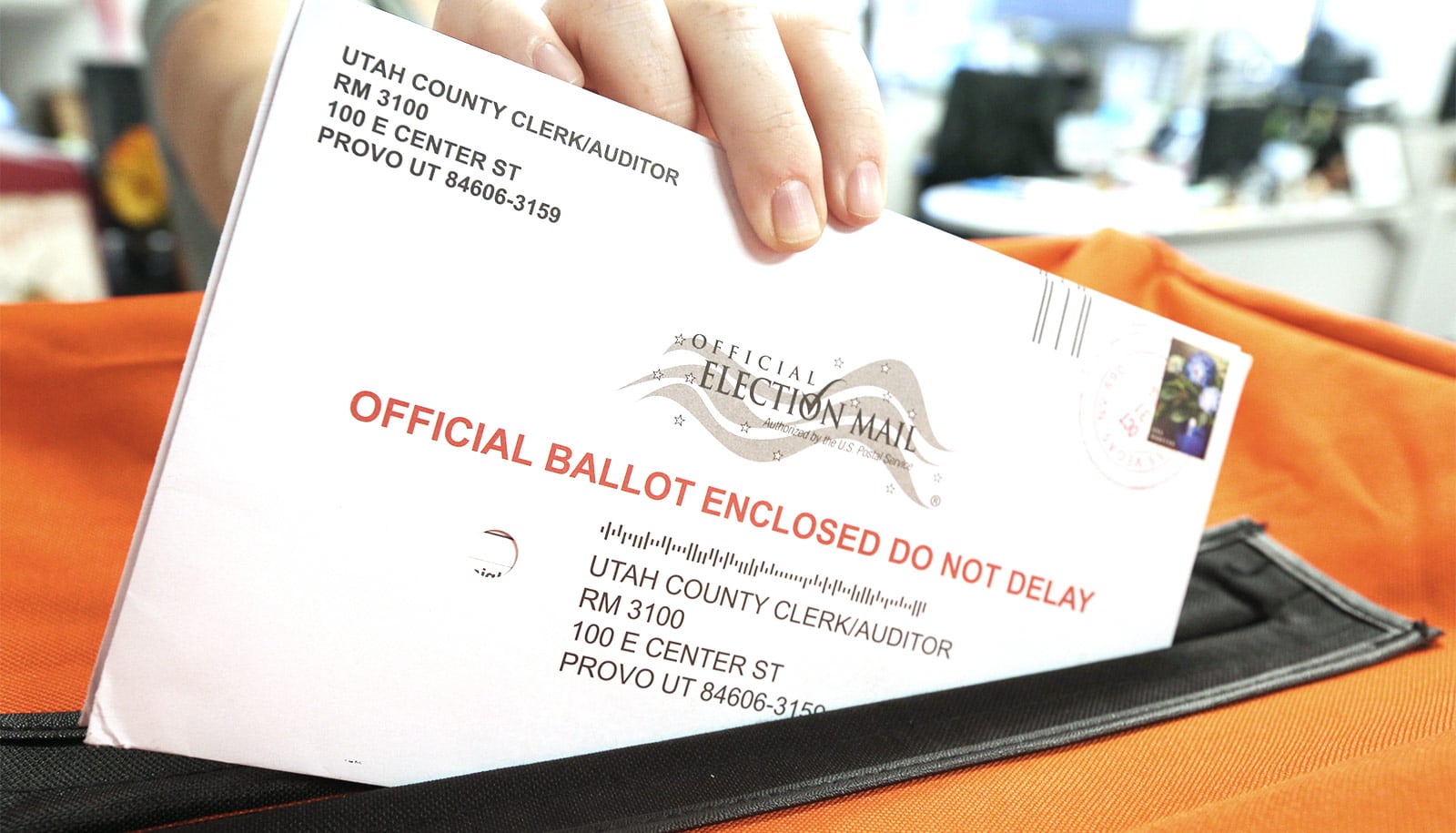

The coronavirus has disrupted state primaries and forced the prospect of major reforms for the 2020 election. Election officials across the nation are mulling expansions or transitions to mail-in voting while Congress is fielding calls for a nationwide vote-by-mail program.

Democrats and Republicans alike have voiced concerns that mandated vote-by-mail might disadvantage their party in November.

“Claims that vote-by-mail fundamentally advantages one party over the other appear overblown.”

Which party should be concerned? Neither, according to the new working paper.

In examining voter data in three states with staggered rollouts of vote-by-mail programs—California, Utah, and Washington—the researchers found that the introduction of mail-in voting did not have an effect, on average, on the share of voter turnout for either Republicans or Democrats.

Researchers also found that expanding vote-by-mail does not appear to increase the vote share for candidates of either political party. Taken together, the researchers say their findings essentially dispel concerns that mail-in voting would cause a major electoral shift toward one party.

“Our paper has a clear takeaway: Claims that vote-by-mail fundamentally advantages one party over the other appear overblown,” the researchers state in their working paper.

What’s more, voter turnout overall modestly increased by two percentage points, they found.

As partisan rhetoric around voting reforms ramped up after the March primary and shelter-in-place restrictions widened, the researchers turned to data to help address the question of which political party, if any, benefitted from mail-in voting.

“There are a lot of questions about how we would implement vote-by-mail, how much it would cost, and what groups it might affect,” says coauthor Andrew Hall, a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) and professor of political science in Stanford University.

“Our research here doesn’t speak to all of these questions, but it addresses one key issue—and shows that, in normal times, expanding vote-by-mail does not advantage either party.”

“That should be useful information for people who are trying to drive bipartisan support for expanding vote-by-mail for the 2020 elections,” he says.

States that already have voting by mail

Six US states have adopted some form of voting by mail in recent years, and the researchers chose to study California, Utah, and Washington because their staggered rollouts in counties allowed for streamlined comparisons of results from counties with or without mail-in voting within a state, over time.

They examined voter data from 1998 through the 2018 midterm elections, making their study the largest, most up-to-date analysis yet of partisan effects of voting by mail.

“We could do this research because vote-by-mail policies have grown, and we were able to look back at two decades worth of data on policy changes as one big study rather than looking only at one state,” says coauthor Daniel Thompson, a PhD student.

Their main findings reveal neutral partisan effects on average across many different tests.

For instance, the researchers note that the change in share of voters who are registered as Democrats—which some Republicans fear could increase with vote-by-mail elections—ranges from -0.1 to 0.3 percentage points.

And while California and Washington are considered blue states—and Utah, red—the analysis takes into account political differences found across the counties and the states.

“There isn’t a difference in our estimated effects if a state is largely Democratic or Republican,” Thompson says. “And we don’t have any reason to think, coming into this, that there are going to be big differences in partisan outcomes across other places.”

‘Normal times’ vs. the ‘new normal’

It’s important to note limitations of the study, however, the researchers says.

A key caveat is how the analysis examined partisan effects during “normal times”—before the coronavirus outbreak. Today, it’s anything but normal, and it remains unclear how the impact of the pandemic will play out—who or what regions will be more affected than others.

“Comparing a new vote-by-mail system to this ‘new normal’ is beyond what our data can do,” Hall says. “But we can say that, in general, there is nothing fundamental about voting by mail that advantages one party over the other.”

And depending on how mail-in voting programs are implemented, Democratic or Republican voters may end up being disproportionately affected.

“It’s always possible to administer any electoral system unfairly—I don’t think this is anymore true for voting by mail than for any other system. And the public needs to monitor election administration closely,” says Hall.

In the weeks ahead running up to the 2020 election, “there are many considerations in deciding whether to extend vote-by-mail, and our paper provides a useful data point on the question of whether it would have partisan impacts,” he says.

Source: May Wong for Stanford University