A new book explores the evolution and continued resonance of remembrance rituals in post-World War I Britain.

Each year on November 11, bright red artificial poppies appear prominently across the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth—pinned to clothing, made into wreaths, and placed at monuments, and in more recent years, added digitally to social media profiles. In the years following the war, the poppy became the quintessential symbol of Remembrance Day, itself a commemoration of the end of the First World War and those who died in the line of duty.

“World War I is when many of the rituals we associate with the memorialization of the dead start: poppies, the two-minute silence, listing the names of the fallen, reading certain poems,” says Bette London, a professor of English at the University of Rochester. London explores the rise and evolution of such memorialization rituals in a new book, Posthumous Lives: World War I and the Culture of Memory (Cornell University Press, 2022).

“[Virginia] Woolf is implicitly asking a central question: Who is—and, perhaps more importantly, who isn’t—being memorialized at this moment?”

Hers is a book “about afterlives—the afterlife of World War I, the afterlife of its remembrance, and the afterlife of individual soldiers,” she writes. Following the war, “the scale of loss and its reach across the entire population” prompted a kind of “memorial mania” in Britain and Europe, according to London. In addition to the traditional war memorials such as the Cenotaph at Whitehall and the Edith Cavell Memorial in London, many villages and hamlets in Britain erected their own, more modest memorials.

The devastating loss of life also resulted in a rash of posthumous compilations and publications by family and friends seeking to construct—and commemorate—the lives of lost loved ones. London brings the tools of literary analysis to bear on the range of such source materials: the homemade memorial volumes compiled, and often published privately, by the families of dead soldiers more than a century ago; the life and work of the relatively unknown war poet Charles Hamilton Sorley, who was killed in action at age 20 but became a kind of cult figure for various constituencies; Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, an extended meditation on women’s writing that London argues can be read as a “monument to the unmemorialized”; the campaign to obtain pardons for the shot-at-dawn soldiers who were executed by firing squad for desertion; as well as recent art installations and exhibitions commemorating the World War I centenary.

London’s research illuminates a diversity of memorialization rituals that have taken shape in Britain over the course of more than a century—a diversity that is perhaps belied by the ubiquity of the remembrance poppy:

How did this book about memory and memorialization come about?

It came about in an idiosyncratic way. My previous book was on women’s collaborative authorship and I was interested in forms of authorship that don’t necessarily fit within conventional models. One of the topics I ended up exploring was women mediums who produced automatic writing—writing that they felt was a communication from the dead. While World War I was only peripheral to my authorship project, it was the incommensurate losses of the war that prompted a revival of mediumship in the 1910s and 1920s. I became interested in this larger question of afterlife writing or posthumous writing, but I was doing this research without really knowing where it was going.

Then one day I was teaching a class about women novelists and a line from A Room of One’s Own started echoing in my mind: Virginia Woolf invents Shakespeare’s sister and describes her as a poet who never wrote a word and lies buried in an unmarked grave. I thought to myself, “This sounds just like the way people talked about the young men who died during the Great War,” only those men are remembered everywhere. Many of them were thought of as poets, or would-be poets.

That got me digging more deeply into the actual wartime and immediate postwar sources at the British Library and the Imperial War Museum. It turns out there’s a huge trove of these memorial volumes there. But these young men who are being commemorated in these volumes don’t really have a significant corpus of work, so they’re being memorialized more for their potential, for what might have been. They also didn’t live long enough to be memorialized in a traditional biographical artifact, so the volumes that commemorate them participate in hybrid genres.

I’m interested in understanding the motives behind the reading and writing of these volumes. Who is producing them? How and why are they producing them? And why is it so important to these families that their personal remembrances take the form of a print publication—a book-like object? And I’m interested in the contradictions—between presence and absence, memory and forgetting, public and private—exposed in these productions.

Of the various sites or objects of memory that you analyze in the book, Virginia Woolf’s essay is the only one that is an example of modernist literature. Why did you include it?

Woolf may seem peripheral, but A Room of One’s Own interested me precisely because the war is not obviously its subject. Most people reading it would not think of it as being about World War I or memorialization. But I started thinking about what Woolf might have been doing in reclaiming this space of memorialization through the idea of Judith Shakespeare. Woolf is implicitly asking a central question: Who is—and, perhaps more importantly, who isn’t—being memorialized at this moment? She becomes part of the way to ask, “Where are the women when we’re remembering World War I?” Scholars have now become more interested in looking at women novelists who were writing about the war and in the letters, diaries, and published narratives of wartime nurses and other women war workers. But Woolf was writing from a civilian position in what I take to be a kind of resistance to the war and to its memorialization. At the same time, her work testifies to the extent to which the war permeates the British consciousness at this historical moment.

Speaking of the unmemorialized, what’s the “shot-at-dawn” campaign, and why do you find it significant?

The shot-at-dawn campaign was an effort in the early 1990s and 2000s to obtain pardons for some 300 British soldiers who were shot for alleged cowardice or desertion. It’s an example of one of the most radical ways in which memory of the war has changed over time. During the war and immediately after, nobody wanted to talk about these hundreds of soldiers.

If Woolf was calling attention to how women were being overlooked, these solders were deliberately and actively being unremembered at the very moment when naming every soldier was seen as paramount. Then, starting at the end of the 20th century, you see this movement to remember them. The shot-at-dawn soldiers are an extreme example, but they provide an opportunity for us to reevaluate these larger practices of remembrance.

How would you articulate the difference between memory and remembrance? Why is the distinction important?

There are scholars who work in memory studies and other fields who emphasize the finer points about the differences between terms like memory, remembrance, commemoration, memorialization. It can get complicated. I think it’s most useful to distinguish between remembering as something that one has actually experienced, which I call memory, versus the process of ritual remembrance, which encompasses a collective or public notion of people coming together. Another operative term for me is post-memory, since a recurring concern of the book is the question of how remembrance practices change when the war drops out of living memory.

A national narrative about World War I was, you note in the book, “slow to emerge” in places like Poland and Austria. Similarly, the British preoccupation with the Great War “finds no echo in the United States.” Why does World War I have a particular hold on the British imagination?

I think there are a number of different factors. World War I was just such a shock to the British consciousness after a long period of peace. It was also a war that wasn’t being fought by a professional army, but instead cut across the entire culture. So, it reached people who would not normally have had a direct experience of war.

The fact that the war was not fought on British soil may, in some ways, have made memorialization more important and more urgent in the British consciousness, especially since they decided not to repatriate the bodies of those who died. You couldn’t just go to the grave of someone who died. So, there became a practical need to construct local memorials, but also to discover new and different ways to memorialize.

There’s also a way in which the war came to inhabit popular culture, at least partly through the war poets. People glommed onto them for seeming to offer a connection to this experience of devastating loss. One can imagine how poetry that came out of the war spoke to something that was already embedded in British culture. And in more recent times, the First World War has become institutionalized in the British education system, such that people are memorizing the war poets and going to visit war graves.

Part of the memorialization impulse is also an attempt to give meaning to the losses incurred as part of a war that would come to be seen by the 1960s as one of futility, as one of waste.

How do you see the trope of posthumous lives operating in our current digital age?

In a variety of ways, including how images, words, memorials get distributed—not to mention the level of access available to different kinds of information.

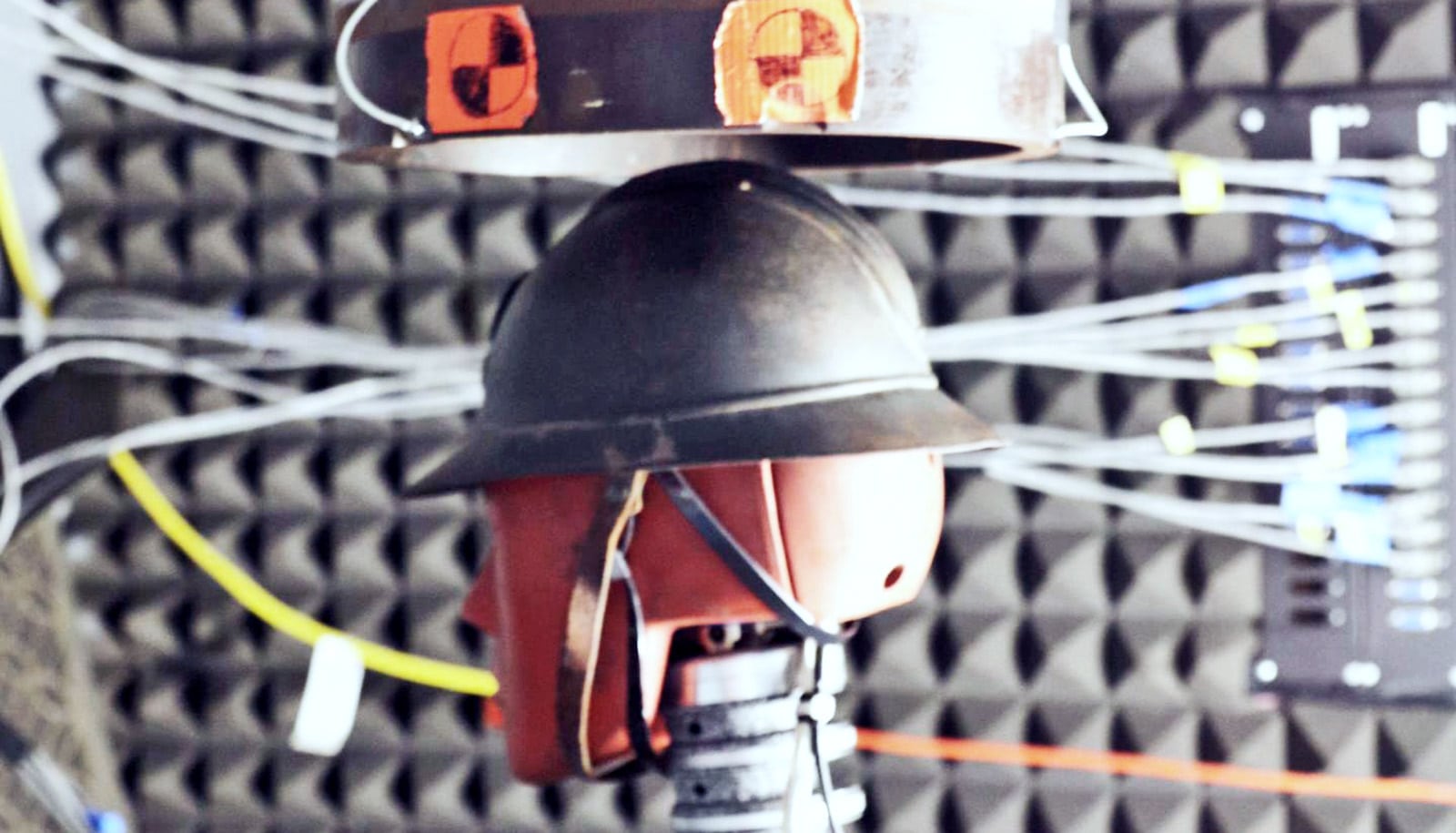

I’ll give you a personal example: My family participated in a COVID memorial project at the Brooklyn Museum called A Crack in the Hourglass. It’s a media project that was advertised as a transitory “anti-monument.” The idea was to create a kind of digital archive, at a time when people couldn’t gather together to mourn publicly. You submit a photograph of your loved one who died from COVID, along with a dedication, and the image is reproduced in this ghostly way with a robotic platform using grains of sand on a black surface. The surface tilts, clearing the space for the next portrait to be reproduced. The ephemerality of the individual images as part of a larger collective called to my mind the question people faced in World War I: How do you visualize and memorialize loss on this scale? That’s a question we’re still grappling with today.

Source: University of Rochester