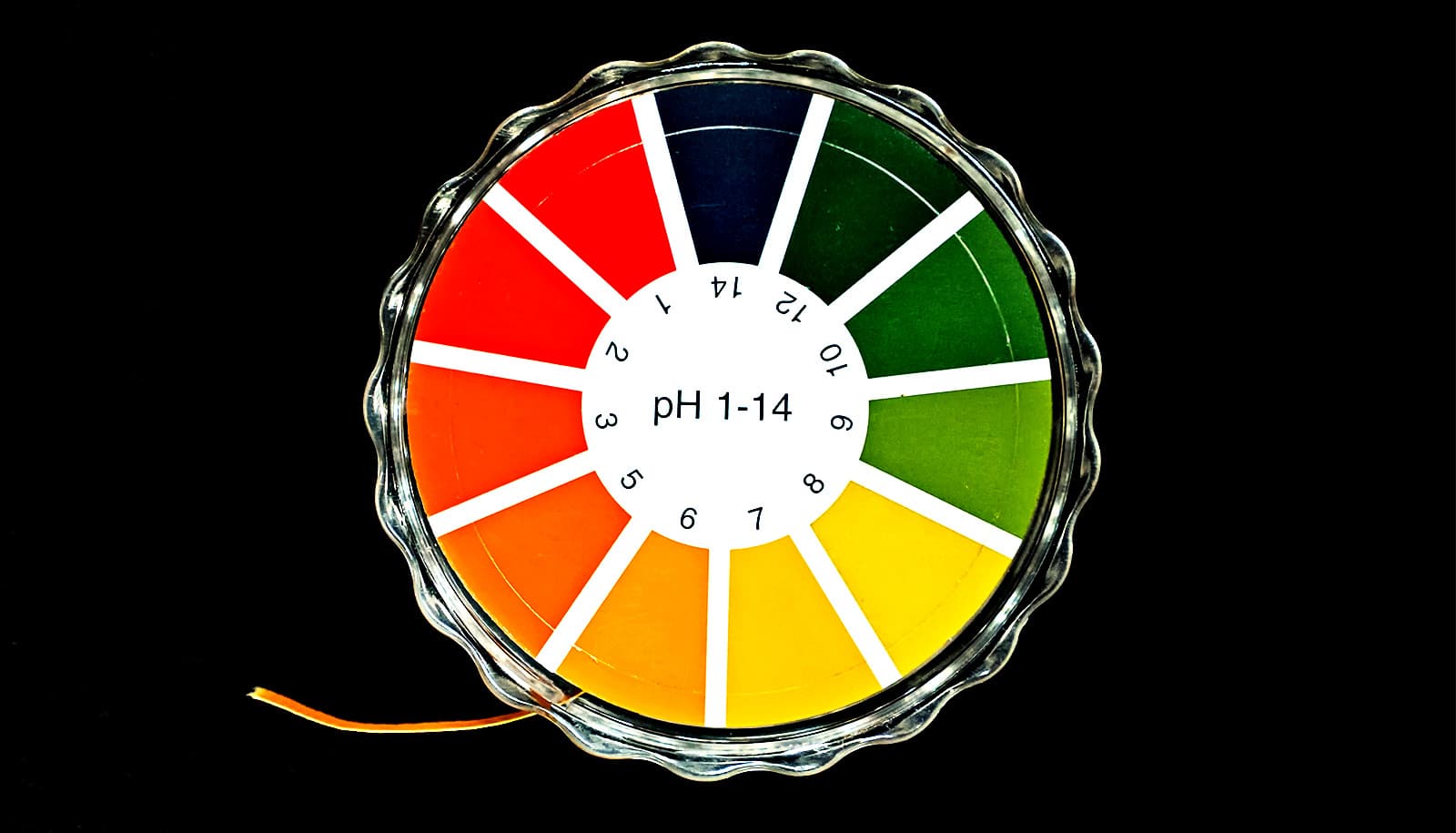

Acidic blood is not the cause of a rare disease called proximal renal tubular acidosis, according to new research.

The disease, pRTA, is associated with loss of a sodium bicarbonate transporter (NBCe1) and is extremely rare, with only about 15 known cases worldwide. In addition to low blood pH, the disease causes developmental impairments and may lead to tooth loss and vision loss.

“The only treatment is alkali therapy, which literally involves ingesting baking soda tablets to normalize the pH of the blood,” says Mark D. Parker, assistant professor in the physiology and biophysics department in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University at Buffalo. He notes that the treatment can be very effective in conditions where the only symptom is low blood pH.

“However, the alkali therapy has never been applied to pRTA patients at an early enough age to determine whether it could prevent the developmental impairments. Our research suggests that these symptoms persist even when blood pH is normalized from birth,” he says.

To conduct the experiments, the researchers developed an animal model analogous to a patient treated with alkali therapy in utero and beyond. The mice have the sodium bicarbonate cotransporter NBCe1 in their kidneys, which is missing from patients with pRTA, so their blood pH is normal, but both in patients and the mice it’s missing from all other cells in the body. That means they cannot take bicarbonate up into their cells.

“This mimics the situation where the blood pH has been cured of its defects, but the patient still lacks NBCe1,” says Parker.

“In short, we found in these mice nearly every single sign that individuals with this disease have, except the low blood pH. The mice have corneal edema, weak enamel, are short, are underweight, and have increased mortality,” Parker explains. “So it turns out that few of the signs of this disease are due to acidic blood. Thus, alkali therapy is not a panacea for this disease.”

Potential therapies that might address symptoms would need to involve replacing the pathway that would allow sodium bicarbonate to get into cells, possibly involving gene therapy, Parker says.

The research also provides some insights into the genetic mutation that causes the condition. Parker says that some of the scientific literature suggests that this gene, SLC4A4, may also be involved in cystic fibrosis and other more common diseases. For that reason, these results may become relevant to conditions such as kidney failure and osteoporosis that may present with similar symptoms.

The research appears in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

Additional coauthors are from the University at Buffalo and Williamsville East High School. Funding for the research came from the National Institutes of Health National Eye Institute and the ASN Foundation for Kidney Research. The Gene Targeting and Transgenic Shared Resource at the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center generated the animal model.

Source: University at Buffalo