The easier and safer it is to get to a park, the more likely people are to visit the park frequently, research finds.

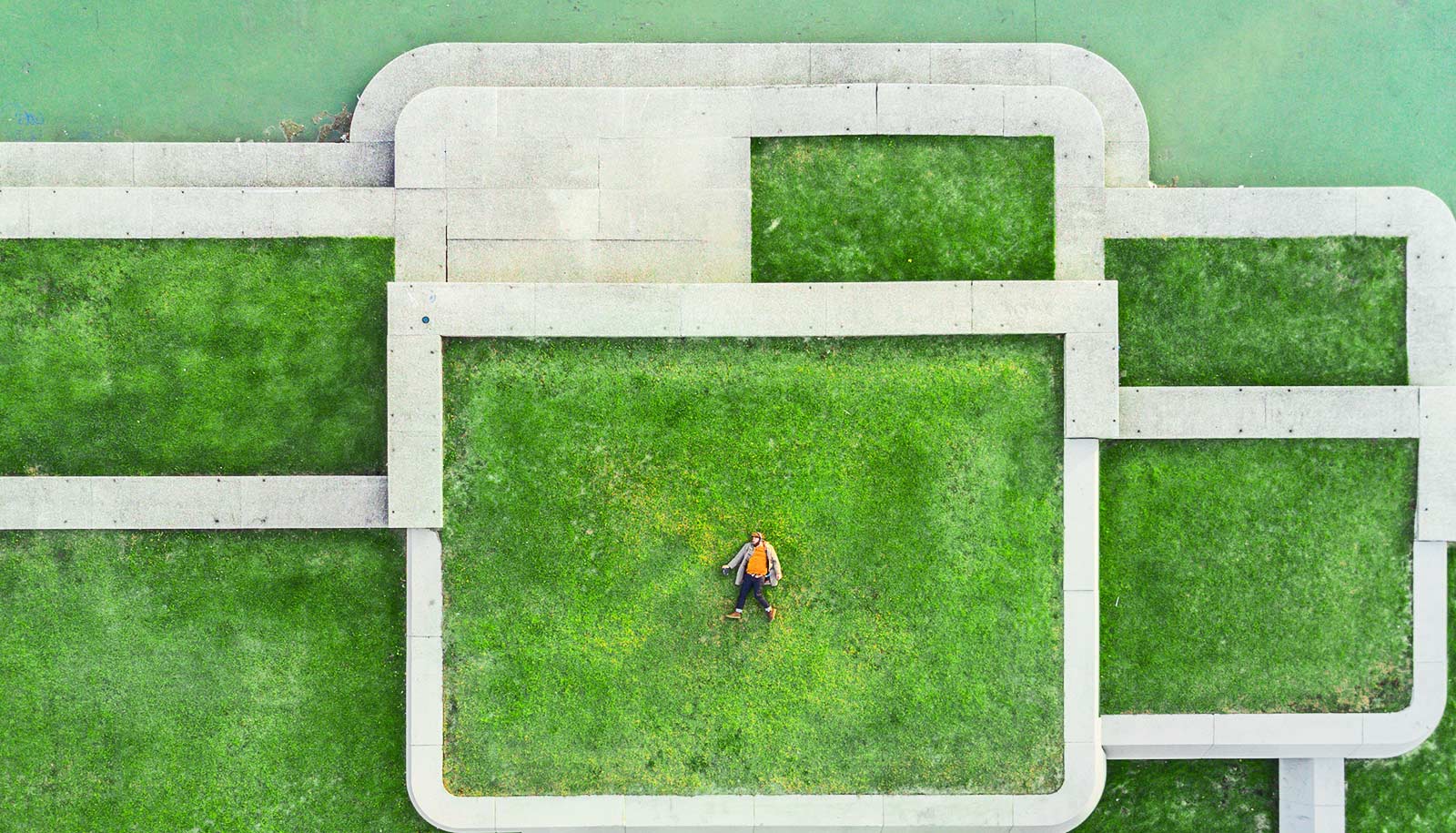

If city planners want more people to visit community greenspaces, they should focus on “putting humans in the equation,” according to the new study in Landscape and Urban Planning.

Adriana Zuniga-Teran, assistant research scientist at the University of Arizona College of Architecture, Planning, and Landscape Architecture and the Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy, studies greenspace in cities. She says walkability—or how easy and safe it is for someone to walk from home to a greenspace—is a deciding factor in how often people visit parks.

The path to the park

Researchers gathered data from people in Tuscon, Arizona parks as well as from people in their homes, which Zuniga-Teran says is significant, as most similar previous efforts she could find focused exclusively on one group or the other.

“We might think we are designing walkable neighborhoods, but people might not feel like that.”

The data from those surveyed in their homes show that several factors that play into a neighborhood’s walkability can significantly increase how often people visit greenspaces. For example, higher levels of perceived traffic safety and surveillance—or how well people inside nearby buildings can see pedestrians outside—corresponded with more frequent visits.

The research also suggests that people who travel to greenspaces by walking or biking are three-and-a-half times more likely to visit daily than those who get there by other means. Residents who have to drive are more likely to go only monthly.

Proximity to a park, though, played no significant role in how often people visited a park, Zuniga-Teran says. “This was surprising because oftentimes we assume that people living close to a park are more likely to visit the park and benefit from this use.”

Different levels of walkability may explain this result. “Let’s say you live in front of a huge park, but there’s this huge freeway in the middle,” Zuniga-Teran explains. “You’re very close, but just crossing the major street, you might need to take the car and spend a long time in that intersection.”

In situations like that, she says, a person probably won’t visit that park frequently despite living close to it.

Public greenspaces

The team of researchers gathered data from more than 100 people visiting Rillito River Park and found only one walkability factor was significantly linked to more frequent visits: traffic safety. Those in the park who indicated their neighborhoods have fewer traffic-related safety concerns were one-and-a-half times more likely to visit greenspaces daily than those who reported concerns about traffic-related safety.

Unlike the people surveyed in their homes, those surveyed at greenspaces indicated that proximity is a major factor in how often they visit, with those who live close to greenspaces being six times more likely to go daily.

It’s important to gather and use this kind of information for the sake of human and environmental health, Zuniga-Teran says. Greenspaces clean the air and water, which benefits every resident of a community, she says. And when people use parks, that greenspace is more likely to be preserved.

It’s up to community planners to use the research to shape policy, so that neighborhoods are developed in ways that connect residents more easily and safely with public greenspaces. For example, she says, the continuing emergence of gated communities can interrupt the flow to greenspaces. Cul-de-sac-heavy neighborhoods can do the same thing. Developers of those types of neighborhoods, Zuniga-Teran suggests, could work with city planners to “open a door to the park” by creating pathways that enhance connectivity.

Developers also could use the findings as a springboard into looking into whether their perceptions of walkability match those of the residents living in their communities, she says.

“We might think we are designing walkable neighborhoods,” Zuniga-Teran says, “but people might not feel like that.”

The next step, she hopes, is that researchers will take a deeper dive into what amenities or design features can draw new people into parks. Those could range from additional lighting and separate bike lanes to more accessibility for people with disabilities. Her team is continuing the effort with more detailed surveys in Tucson this summer.

Source: Andy Ober for University of Arizona