Getting vaccinated against measles is not only religiously acceptable, but also a religious obligation, according to an expert on health law, ethics, and Jewish studies.

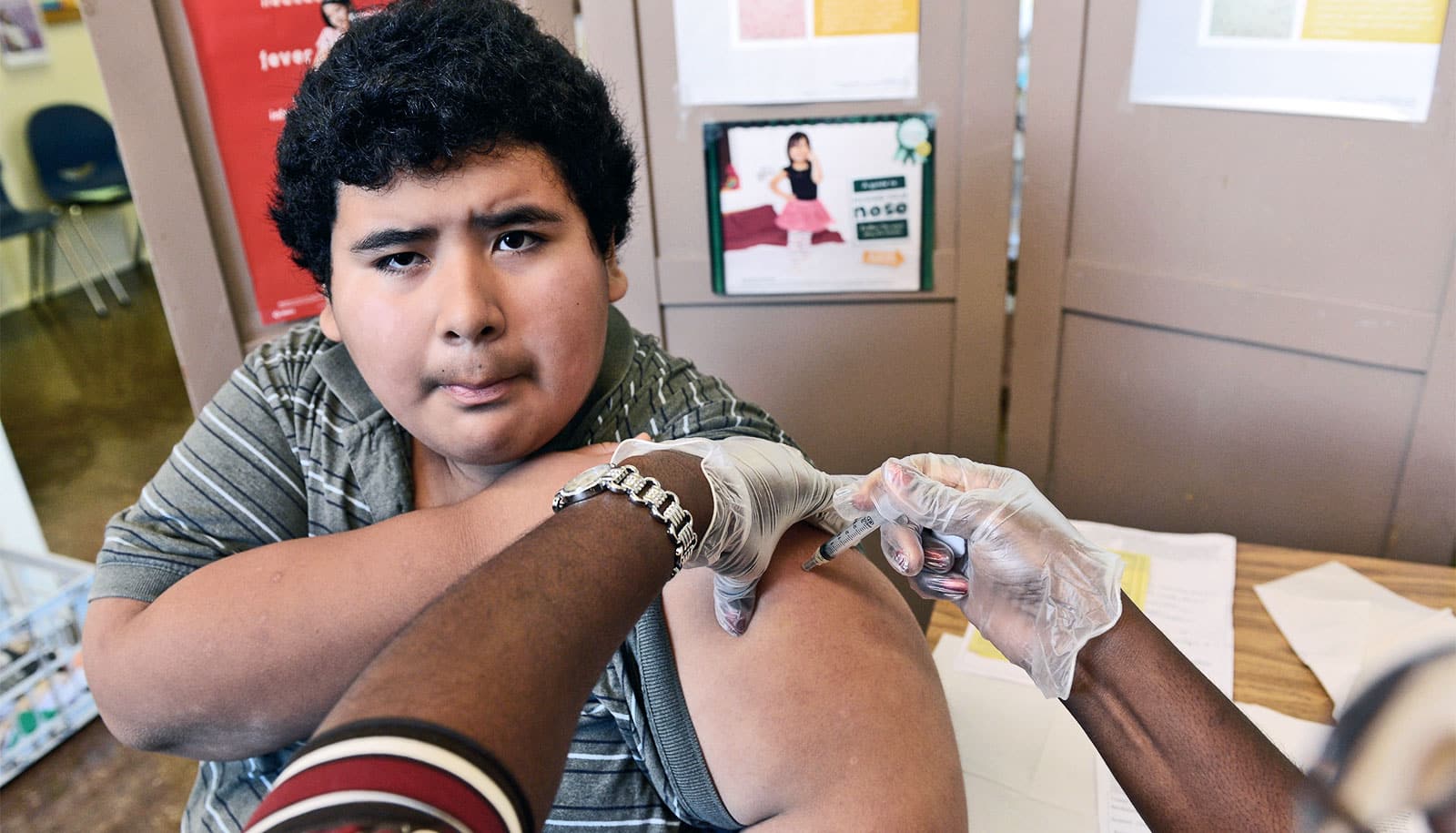

The measles vaccine (which is typically combined with mumps and rubella—known as the MMR vaccine) is 97 percent effective at preventing measles after two doses. But with 764 confirmed cases and rising, the United States is experiencing the largest outbreak of measles since 2000, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had declared the highly contagious disease eliminated thanks to vaccination.

Worldwide, the World Health Organization reports a 300 percent increase in the number of measles cases since the beginning of 2019. The cause? The number of unvaccinated people has been growing, causing a global spike in measles.

A deadly outbreak

It’s a worrisome turn of events. Despite how easily vaccination can prevent measles, Rachel Fearns, an associate professor of microbiology at Boston University and an investigator at the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories, wants us to remember that “it is not a benign infection, at all. One in 1,000 cases can cause brain swelling and one in 1,000 cases can result in death,” she says.

WHO officials say the root cause for this global increase is poverty, preventing many medical systems around the world from being able to vaccinate enough of the population to quash the measles virus.

The current US outbreak has its roots in Ukraine, where almost 70,000 people have contracted the virus since 2017. The link? Each year, on Rosh Hashanah, many Orthodox Jewish men make an international pilgrimage to a religiously significant site in Ukraine.

Last year, the Rosh Hashanah pilgrimage occurred in early September. By October, nearly 1,000 measles cases had popped up in Israel. The first known US patient, a child from Brooklyn, was diagnosed that same month after a trip to Israel. Now, the outbreak has hit unvaccinated people living in Brooklyn and Rockland County, New York, the hardest.

Vaccines and religion

Michael Grodin says that Jewish schools called yeshivas have been an epicenter for the virus to spread in New York because a high percentage of ultra-Orthodox Jewish parents don’t vaccinate their children for a multitude of reasons. This is putting everyone else at risk, says Grodin, a professor of health law, ethics, and human rights at the Boston University School of Public Health and a professor of Jewish studies at the Elie Wiesel Center.

Grodin says that these New York communities are outliers, caused in part by rabbis who have misunderstood or have refused to believe facts about vaccine safety. Overall, the vast majority of Jewish Americans have been vaccinated, and many prominent rabbis have encouraged people to get themselves and their children vaccinated.

“It should be an absolute duty to protect children,” Grodin says. “This should not be a complicated issue. Rabbinic leaders should say, not only [are vaccines] acceptable, but [they are] required and mandatory.”

While training in the mid-1970s and practicing as a pediatrician at the former Boston City Hospital (which later joined with Boston University Medical Center Hospital to become the Boston Medical Center of today), Grodin frequently saw children infected with the measles virus. He says that vaccine exemptions should only be made for medical reasons.

“Life takes precedence over any religious precept.”

“The problem with measles is that you are contagious before you have the symptoms,” says Grodin, who teaches Jewish bioethics, which largely focuses on applying Jewish texts and values to address contemporary medical issues, including vaccinations.

Religious or philosophical vaccine exemptions, which many states including Massachusetts permit, should be allowed only on a case-by-case basis, provided that such an exemption does not put others at risk, he says.

“I would argue, and most rabbis would argue, that it’s not only acceptable to get the MMR vaccine, but a religious obligation,” Grodin says. “Life takes precedence over any religious precept.”

In the meantime, public officials are working to contain the outbreaks. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio declared a public health emergency in early April 2019 that would require unvaccinated individuals to receive the MMR vaccine, with possible fines of up to $1,000 for those who do not comply.

MMR vaccine history

For the measles component of the MMR vaccine, we have a 13-year-old boy from Boston to thank, explains Fearns. In 1954, scientists started developing the measles vaccine by taking the virus from the young Bostonian and growing it over and over again in chicken embryos. This caused the virus to genetically mutate so it could no longer infect cells in the human body, but could still create enough antibodies to protect against the communicable version of the virus.

Between 1954 and 1968, scientists continued to grow and mutate the virus until a more effective measles vaccine was created. The 1968 version of the vaccine is still in use today and the CDC is recommending people who were vaccinated prior to 1968 get revaccinated with at least one dose of MMR.

Experts also suggest people born during or after 1957 who do not have evidence of immunity get the MMR vaccine. Fearns recommends consulting your doctor if you are fearful of exposure or if you are concerned about your vaccination history.

“The vaccine stimulates a very natural process,” Fearns says. “You are basically stimulating your body to do what it has evolved to do and what it’s supposed to do.”

Source: Jessica Colarossi for Boston University