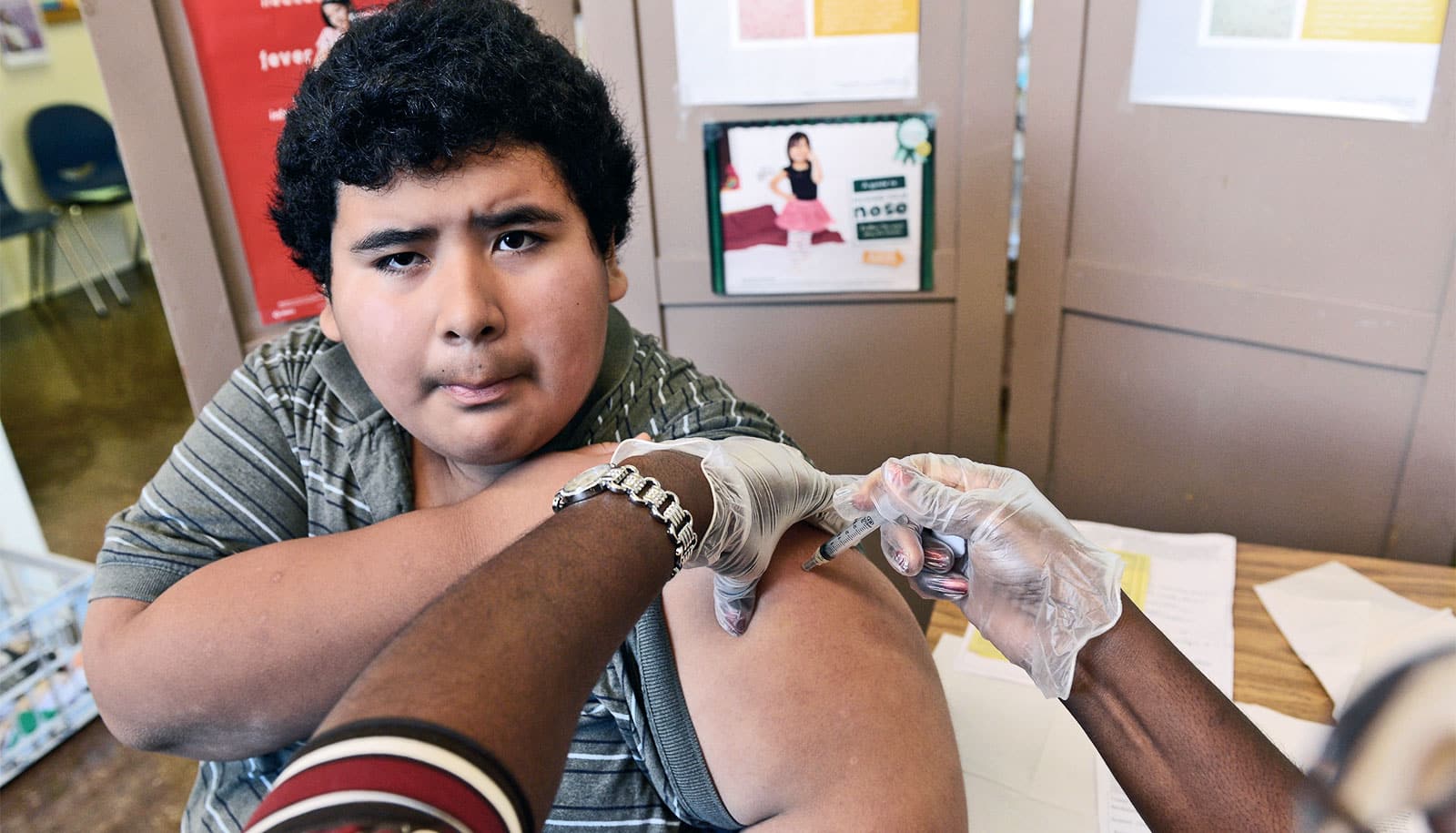

The measles outbreak in the US continues to grow, with more than 100 cases reported across the country—most involving young children who have not received immunizations.

Here, Michael Wald, a professor at the Stanford University Law School and an expert on legal policy related to children, discusses the legal rights of children to receive vaccinations and how the law varies from state to state:

What authority do states have to require that children receive vaccinations?

States clearly have the authority to require that all children receive vaccinations. Vaccinations serve two purposes. One is to protect the health of the child, the other to protect the health of the general public.

As early as 1905, the US Supreme Court ruled that parents do not have a constitutional right not to vaccinate their children, regardless of the reason, since these laws are justified in order to protect the general public health. Under most state laws, failure to provide vaccinations might also be considered “medical neglect” if the vaccination is needed to protect the child from serious physical harm.

All states have mandatory vaccination laws. These are generally enforced through making vaccinations a requirement for school enrollment, including preschool and daycare. Enforcement through child welfare laws is not very common, since child protection laws generally require the threat of serious harm to the child, which may be hard to establish.

Can you talk about how and why vaccination regulations for children attending school vary from state to state, with religious and other exemptions? Why isn’t this handled at the federal level?

Virtually all states provide religious exemptions to mandatory vaccination laws; many also provide a “philosophical” exemption. While the federal government might be able to require universal vaccination for the protection of the general public, issues related to the protection of public health and to child protection generally have been seen as the province of the states and best regulated at the state level.

There are some federal guidelines regarding what constitutes the provision of adequate medical care for purposes of child maltreatment laws; the federal government makes adherence to these guidelines a condition for receiving federal grants, but the federal government has not established direct regulatory power.

In states that have fairly tight regulation we can still see a measles outbreak in communities where a significant number of children are home schooled. Why not require vaccination for all children?

Parents who object to vaccinations, for either religious or philosophical reasons, have strong lobbies in many states. They receive support from legislators who see decisions regarding health care, like decisions regarding schooling, as an aspect of parental rights. However, in most states, exemptions from vaccination laws can be overridden if the failure to vaccinate creates a substantial risk of serious harm to public health. For example, in the event of an outbreak of a communicable disease a state may order that a child be vaccinated.

When does the law consider a child to be an adult? Is there a federal definition?

In general, the age is 18, but the age varies for different purposes. There is no general federal definition.

There have been reports of a number of teenagers across the country questioning their parents’ decisions not to vaccinate them. I understand that in some states, children younger than 18 can seek medical attention without parental notification. Is there a general federal rule about this? Or is it state-by-state regulation?

There is no general federal rule. Many states give children, usually over the age of 12, the right to get some types of health care, including access to contraception and abortion without parental permission. These laws are based on the judgment that requiring parental consent, or even informing parents, can cause serious harm to some children. These laws generally have not covered a right to receive vaccinations, although in some states a “mature” minor may have the right to object to vaccination on religious grounds.

How might lawmakers across the country address this challenge of parental rights vs. the health concerns and rights of their children? How is the law developing in this area?

In recent years, three states, including California, have repealed exemption laws. It appears that the number of parents objecting to vaccinations is growing. If this leads to more outbreaks of serious diseases, the politics in other states may change.

Is there a comparison here to parents who have withheld medical intervention from their dying children for religious beliefs? What does the law say about the rights of children to protect their own health—and the medical community’s obligation to intervene when parents refuse medical help for their children?

Parents do not have the right to withhold medical care from their children if there is a substantial threat of serious harm. Courts regularly require care in cases where there is a threat of death, at least if the need for, and value of, the medical care is clear.

Is it possible that a parent might be charged with a crime if a child was not vaccinated and dies?

It would be very, very unusual circumstances where the parent would have had to know that there was a high likelihood of death or serious physical injury. I do not know which vaccines might fall in this category.

Source: Sharon Driscoll for Stanford University