In addition to providing practical information, maps can offer insights into history, identity, and power structures, a new book shows.

The stories maps tell—and particularly the way they can show how some troubling aspects of the colonial past continue to affect our present—are primarily what interest Kyle Wanberg, a clinical associate professor in global liberal studies and author of the new book Maps of Empire: A Topography of World Literature (University of Toronto Press, 2020).

“There is a haunting effect of old maps,” says Wanberg, citing one example of how boundaries set down on paper decades ago continue to determine how people live and think now. “A map of Africa in 1885, after European leaders divided up the continent at the Berlin Conference, looks eerily similar to the map of the continent today.

“It is important to understand that the lines drawn at the end of the 19th century split up communities, cut off traditional trading networks, and brought people together in a haphazard way, resulting in new identities and collectivities.”

And maps, with their power to shape narratives, Wanberg argues, have deeply influenced culture, including literature.

“Maps have continued to shape social and cultural ideas of national or imperial affiliation,” he writes in Maps of Empire, adding: “Literature that is tied to a sense of place, recreating and reimagining the cultural and social possibilities of that place, has this very transformative potential.”

Here, Wanberg speaks about maps as a historically underappreciated force—with a big impact on the written word:

You write that the “world map offers its own narratives concerning history.” What story does it tell?

The world map is a composite artifact with some features that are highly calcified, while others are dissolving and transforming. It is an instrument of empire because that is how it has been most saliently used. If you look at the world atlas, as it is commonly printed, you will often find Europe at the top-center position. The historical narratives offered by the world map are the stories of conquest, nationalism, struggles for independence, and continuing military belligerence that formed and continue to sustain the boundaries of the places on the map.

Artists have challenged this orientation, from Joaquín Torres García’s América Invertida, to Cian Dayrit’s works of counter-geography, including the work, Et Hoc Quod Nos Nescimus, which is on the cover of my book. Considering the stories bound up within these differing spatial representations is especially important for those of us who attempt to write and think about history against the grain.

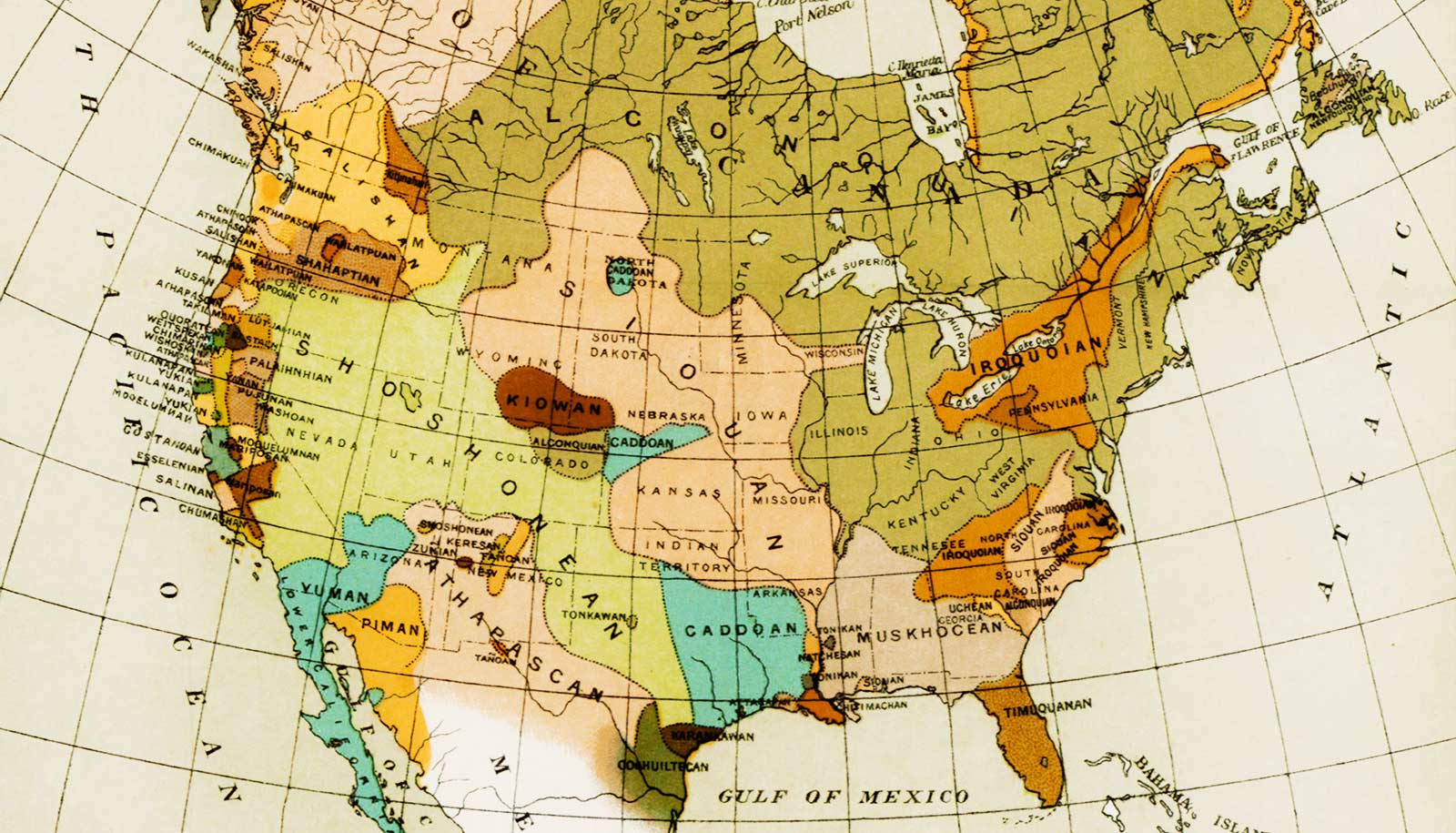

What does the map of the United States tell us—or not tell us—about American history?

The map of the US entails the erasure of the independent Indigenous nations that have been displaced in the course of remaking the world in a particular way through imperialism and cartography. My research suggests that Indigenous groups in the United States have a radically different view of space and geography. In their Ant Songs, for example, the Pima people of what is now central and southern Arizona, as well as northwestern Mexico, use a performative medium to convey the way history and mythic experiences are integral to the landscape and environment.

The richer, more complex view of native topography involves lived forms of knowledge that do not fit so neatly into the settler-colonial map of the US.

You refer to “national hierarchies” that Goethe and other writers established to evaluate literature, privileging works stemming from Europe’s Enlightenment over those from other parts of the world. Is that kind of thinking still a factor in how books are valued today?

Absolutely. In Goethe’s time, this looked different than it does today. Yet national hierarchies still continue to haunt the way works of world literature are judged and interpreted.

Who has access to publishing networks, and who does not? Structures of access and recognition that are distributed through prizes and publishing houses have that way of thinking built into them. Think of the Man Booker prize, which is awarded to works by authors from around the world, but they must be written in English and be published in the UK. It is also an unevenness that maps onto the areas of European and American imperial spheres of influence and interest.

While there may be a growing interest in diverse and international literary voices, the circuits of recognition and distribution may still have roots in uneven structures set up during colonialism. At the same time, there is a common but false assumption that the fruits of this Enlightenment project were derived from and isolated in works of European making. Non-European literary works are often met with certain demands and expectations of authenticity, effectively creating a double standard in the reception of these works.

Your book focuses on colonial maps and how they influenced even post-colonial literature. As we move further away from earlier imperialist eras, will literary works, and our appreciation of them, change?

I would think so. The meaning of these maps is in flux as much as the maps themselves.

Although the way we respond to literature is not necessarily a response to the conditions of imperialism, these conditions do tend to have an influence on our readings, especially when we are least aware of this influence. During the mid-20th century, literary representations and their reception were changing because multiple liberation movements were struggling against political colonialism and transforming the world in the process. It was a moment of great expectation and possibility. What followed in many places was the disenchantment in response to continuing forms of colonialism in spite of the political gains of independence, giving rise to new directions in postcolonial literature. But my book argues that these earlier works and genres remain relevant, because they address the very structures that were supposed to have been abolished by now.

Maps of Empire is anchored in topography, which is characterized by both natural and human-drawn boundaries. But today, we are quite familiar with topography of a different sort—one engineered by technology, which, as you note, creates “echo chambers rebroadcasting and amplifying politicized hatreds and racializations.” Is technology supplanting maps as a force that affects our understanding and appreciation of literature?

It is not that the map is going away; it is only becoming ubiquitous. Maps, as instruments, are already a kind of technology. Yet more sophisticated forms of geo-spatial maps are certainly supplanting the older paper map. I think we are becoming maps ourselves in the sense that we are entering into the map as points of data. The places we visit, the things we like on social media, the purchases we make, are contributing to new maps that chart predictable behaviors and anticipated responses. This kind of surveillance creates new understandings and experiences of space and the dynamics of power that shape and organize it.

Literature becomes just one more dataset, pairing audiences with commodities. Cartographic elements are being remade in these spatial-temporal maps, and much like the paper maps which served imperial desires so faithfully for a time, the biases of those creating and maintaining them remain. But it is important to counter the order of the day with an insurgent literacy that creates other possibilities than the ones we currently face and that the algorithms forecast.

Source: NYU