Sociologist David Cunningham advocates for the arrest and prosecution those who engaged in violence or other criminal action during the January 6 insurrection at the United States Capitol—even though there could be unintended consequences.

In his inauguration speech, President Joe Biden said his administration would confront and defeat the rise of political extremism, white supremacy, and domestic terrorism. Cunningham, professor and chair of sociology at Washington University in St. Louis and author of There’s Something Happening Here: The New Left, the Klan, and FBI Counterintelligence (University of California Press, 2004), supports the president’s tough approach.

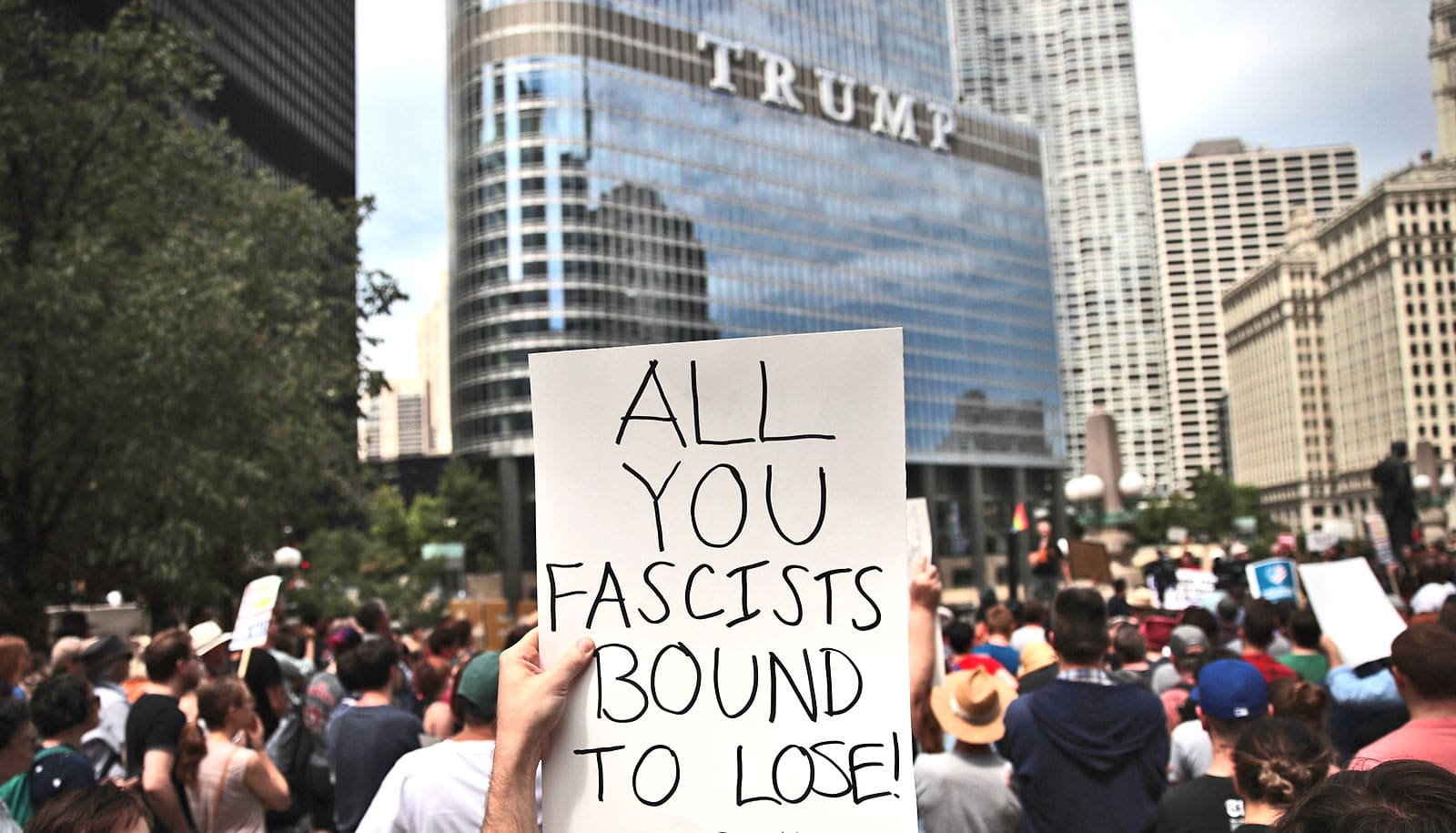

Under Trump’s watch, white supremacist groups got bolder. With the implicit, and sometimes explicit, support of the former president, they rallied publicly, circulated conspiracy theories online, and openly participated in the storming of the Capitol in an attempt to overturn the election. Hate crimes—including fatal ones like the 2017 car attack at the Charlottesville counterprotest—also increased.

“…police ultimately deployed their expanded powers not primarily toward the KKK, but instead against the Black and brown targets.”

What many people may not realize is that these groups could see an increase in interest and growth now that Trump has been defeated, Cunningham says.

“Right-wing extremist groups tend to most successfully organize in times when their potential followers feel threatened—that their way of life is under siege. So, we saw significant bumps in the number of active militia and hate groups following the 2000 Census, which spawned the big news that white citizens would be in the minority in the US by the 2030s, as well as around Barack Obama’s election in 2008,” Cunningham says.

“Trump’s defeat signals a similar closing of a window that openly equates ‘greatness’ with white advantage, and white nationalist and extremist groups play on that with calls to defend ‘their’ country and way of life.”

A similar scenario occurred in 1965 after President Lyndon Johnson defeated arch conservative Barry Goldwater, who had the backing of the Ku Klux Klan. Following the election, the KKK experienced a wave of new followers who were energized in their aggrieved alienation from national politics, Cunningham says.

With bipartisan support, the government began to investigate the Klan in March 1965, and formal hearings took place that June. This led police to, for the first time, challenge KKK rally permit requests and aggressively investigate cross burnings and other intimidation tactics they had previously dismissed. By 1969, the KKK had all but ceased to operate as a mass membership organization in North Carolina and throughout the South.

The aggressive moves to dismantle the Klan’s organizational capacity had unintended consequences, though.

“The Klan’s militant core was pushed underground, where it metastasized into lone-wolf or cell-based violence. As a result, the threat posed by adherents became even more volatile,” Cunningham says.

“Meanwhile, though the Klan’s rank-and-file melted away from membership rolls, former members continued to rend the social and political fabric of their respective communities. Research I’ve conducted with sociologists Rory McVeigh and Justin Farrell shows that, after controlling for a wide range of competing explanations, areas where the KKK was active in the 1960s continue to display—even 50 years later—significantly higher levels of violent crime and political polarization.

“Finally, and perhaps most importantly, police ultimately deployed their expanded powers not primarily toward the KKK, but instead against the Black and brown targets—including civil rights and Black nationalist movements—that have always borne the brunt of the state’s repressive apparatus,” Cunningham says.

With this history in mind, Cunningham says Biden and his administration can and should make every effort to defeat the rise of political extremism and white supremacy.

“Doing so, however, shouldn’t require expanding police powers in ways that inevitably will be turned on those who have been seeking justice all along,” he says.