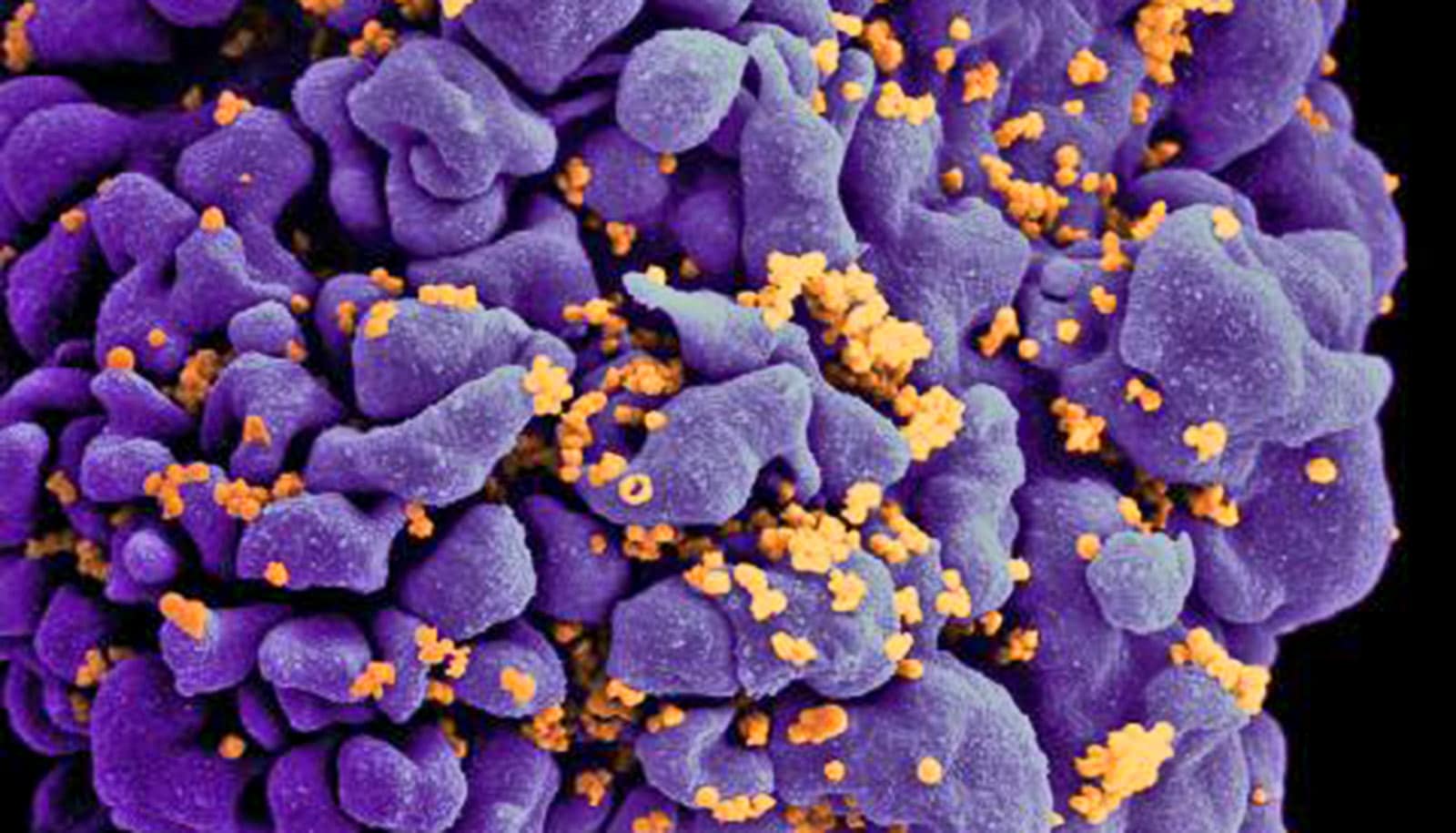

Researchers have taken a critical first step to creating a successful HIV vaccine.

The researchers activated specific immune cells that induce broadly neutralizing antibodies in monkeys. The next phase of the work will now move to testing in humans.

“This study confirms that the antibodies are, at the structural and genetic levels, similar to the human antibody that we need as the foundation for a protective HIV vaccine,” says Kevin O. Saunders, associate professor in the departments of surgery, molecular genetics and microbiology, and integrative immunobiology at Duke University and first author of the study published in the journal Cell.

“We are on the right track,” he says. “From here, we just need to begin putting together the additional components of a vaccine.”

In earlier work, the research team had isolated naturally occurring broadly neutralizing antibodies from an individual, and then backtracked through all the changes the antibody and the virus underwent to reach a point of origin for the native antibody and its binding site on the HIV envelope.

With that knowledge, they engineered a molecule that elicits antibodies that mimic the native antibody and its binding site on the HIV envelope.

Four years ago, Saunders and colleagues published a study in Science in which they established that monkeys made neutralizing antibodies when vaccinated with the engineered immunogen, but it was uncertain if those antibodies were like the broadly neutralizing antibody that is needed for a human vaccine.

In the current study, the researchers made a new, more potent formulation of the vaccine and delivered it to monkeys. This time, their goal was to determine whether the neutralizing antibodies generated in the animals were structurally and genetically similar to the antibodies needed in humans. They were.

“We thought we were on the right track in 2019 and we now have atomic-level detail that confirms those findings,” Saunders says. “It’s an important step forward.”

The National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of AIDS funded the work.

Source: Duke University