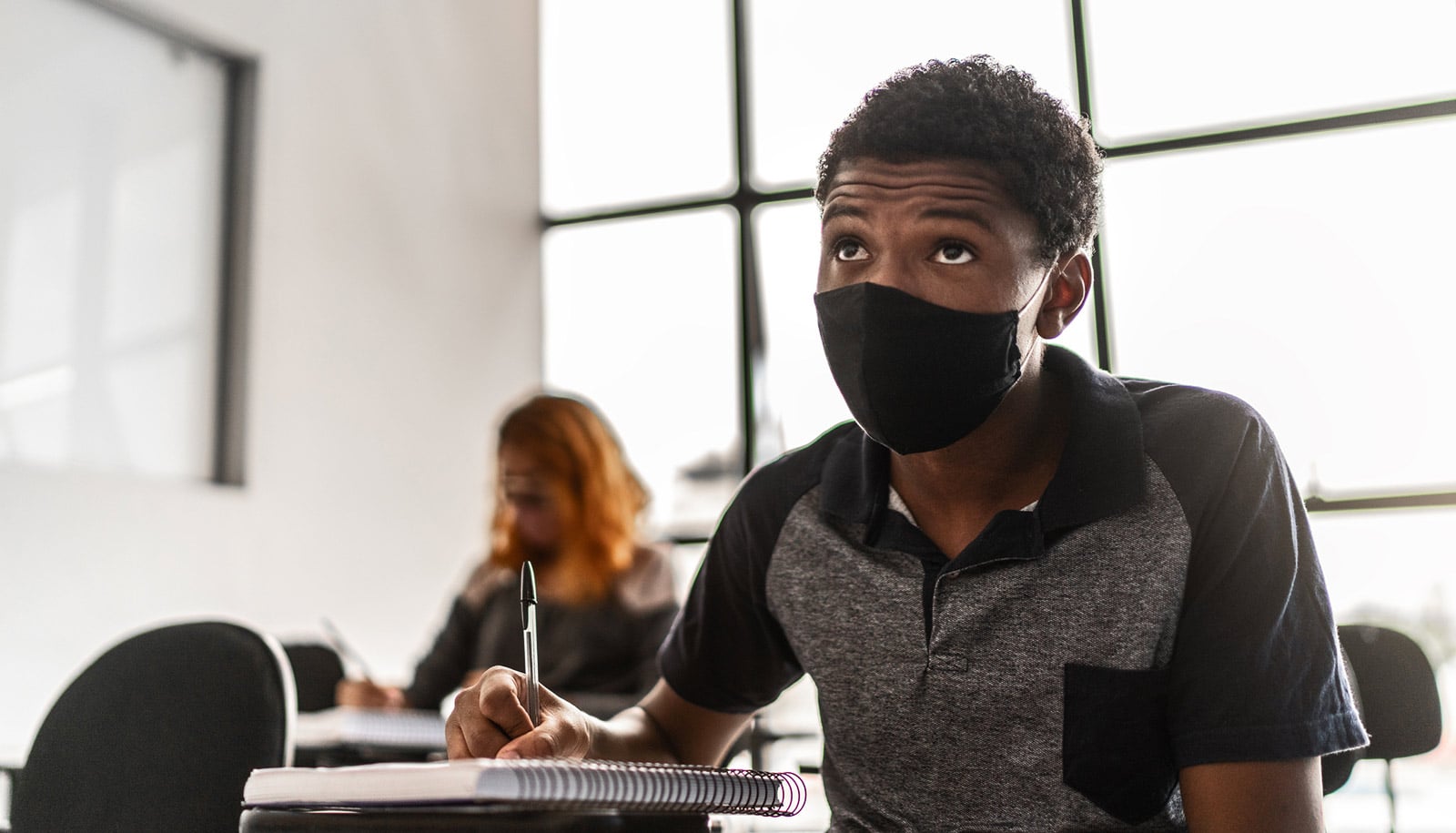

Learning about historical events, especially the roots of racist politics and practices in America, can affect people’s beliefs about systematic racial inequality, research finds.

The researchers—Steven White, assistant professor at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, and Albert Fang, an independent scholar based in New York City—analyzed data from two key studies that surveyed adults who were randomly assigned to learn about the effects of systematic housing, education, and job discrimination that has negatively affected Black communities throughout the United States.

According to Fang and White, they “find compelling evidence that such arguments can increase beliefs in the existence of Black-white racial inequality and increase beliefs in structural causes of racial inequality, particularly among white Republicans and Independents.” They also find evidence that such information can reduce racial resentment among these groups.

The researchers say this demonstrates that exposure to historical information can induce more nuanced thinking about contemporary racial inequalities in the United States.

The researchers conclude that more study is needed for more questions arising from the research. First, they did not observe consistent effects, especially among white Republicans, of historical information on both beliefs about racial inequality’s existence and beliefs in various structural causes of racial inequality.

“We suspect this reflects differences between acknowledging a problem, acknowledging the causes of a problem, and agreeing on the solution. This suggests that even if more Americans acknowledge that racial inequality exists, agreeing on solutions to meaningfully redress it may be more difficult,” the researchers write in the paper.

The findings appear in the journal Politics, Groups, and Identities.

Source: Syracuse University