A new study links defective epithelial barriers to a rise in almost two billion allergic, autoimmune, neurodegenerative, and psychiatric diseases.

Epithelial cells form the covering of most internal and external surfaces of the human body. This protective layer acts as a defense against invaders—including bacteria, viruses, environmental toxins, pollutants and allergens.

If the skin and mucosal barriers are damaged or leaky, foreign agents such as bacteria can enter into the tissue and cause local, often chronic inflammation with both direct and indirect consequences.

“The epithelial barrier hypothesis proposes that damages to the epithelial barrier are responsible for up to two billion chronic, non-infectious diseases,” says Cezmi Akdis, director of the Swiss Institute of Allergy and Asthma Research (SIAF), which is associated with the University of Zurich.

In the past 20 years, researchers at the SIAF alone have published more than 60 articles on how various substances damage the epithelial cells of a number of organs.

The epithelial barrier hypothesis provides an explanation as to why allergies and autoimmune diseases have been increasing for decades—they are linked to industrialization, urbanization, and westernized lifestyle.

Today many people are exposed to a wide range of toxins, such as ozone, nanoparticles, microplastics, household cleaning agents, pesticides, enzymes, emulsifiers, fine dust, exhaust fumes, cigarette smoke, and countless chemicals in the air, food, and water.

“Next to global warming and viral pandemics such as COVID-19, these harmful substances represent one of the greatest threats to humankind,” Akdis says.

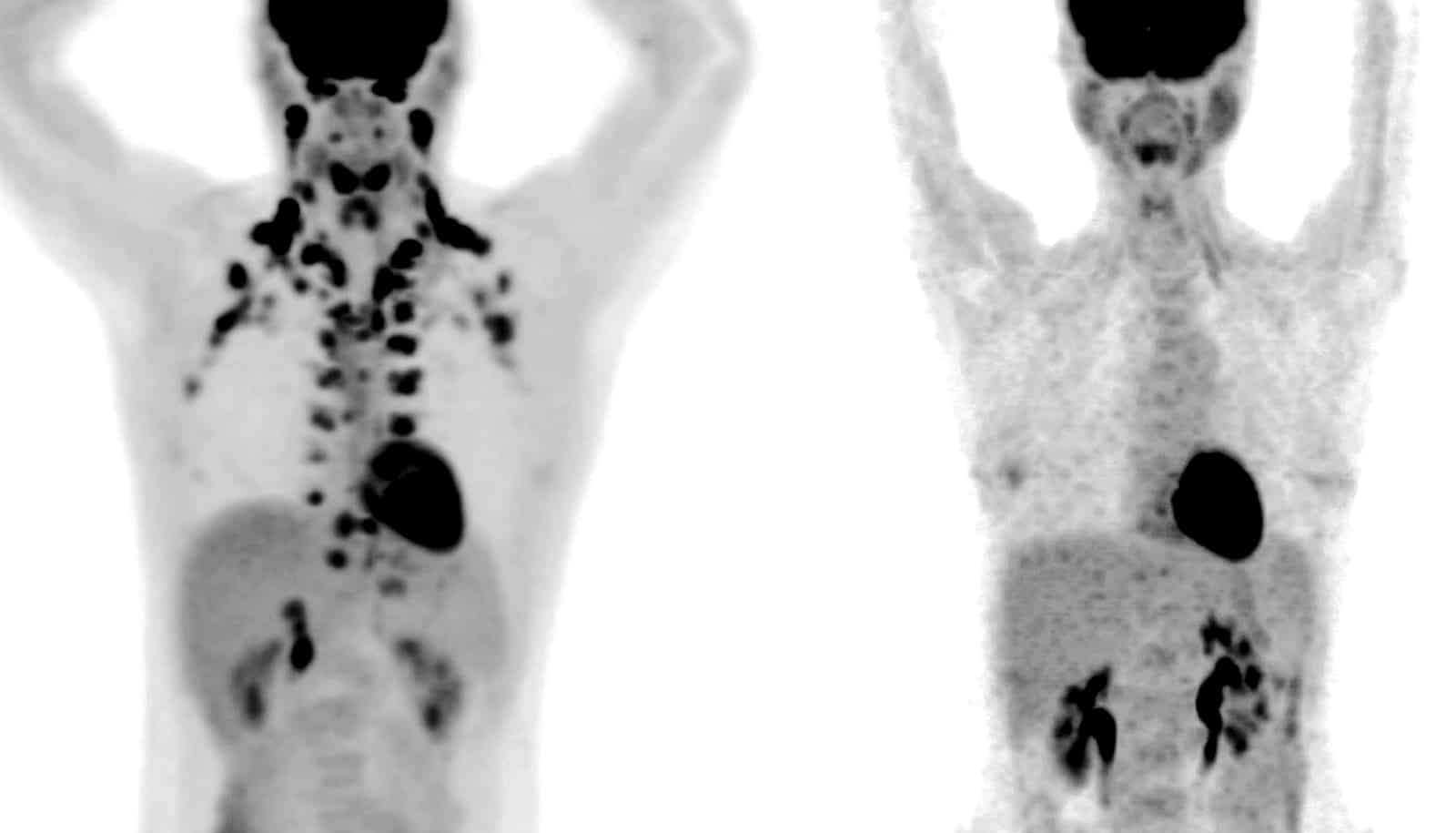

Local epithelial damage to the skin and mucosal barriers lead to allergic conditions, inflammatory bowel disorders, and celiac disease. But disruptions to the epithelial barrier can also be linked to many other diseases that are characterized by changes in the microbiome.

Either the immune system erroneously attacks “good” bacteria in healthy bodies or it targets pathogenic—i.e., “bad”—invaders.

In the gut, leaky epithelial barriers and microbial imbalance contribute to the onset or development of chronic autoimmune and metabolic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, or ankylosing spondylitis.

Moreover, defective epithelial barriers have also been linked to neurodegenerative and psychiatric diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, autism spectrum disorders, and chronic depression, which may be triggered or aggravated by distant inflammatory responses and changes in the gut’s microbiome.

“There is a great need to continue research into the epithelial barrier to advance our understanding of molecular mechanisms and develop new approaches for prevention, early intervention and therapy,” says Akdis.

Novel therapeutic approaches could focus on strengthening tissue-specific barriers, blocking bacteria or avoiding colonization by pathogens. Other strategies to reduce diseases may involve the microbiome, for example through targeted dietary measures. Last but not least, the focus must also be on avoiding and reducing exposure to harmful substances and developing fewer toxic products.

The paper appears in Nature Reviews Immunology.

Source: University of Zurich