A new paper outlines steps that could alleviate the burnout and fatigue that doctors and nurses are feeling in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the recent article in the journal Anesthesia & Analgesia, researchers outline the effects of fatigue and burnout on intensive care unit (ICU) workers.

“The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated an already existing problem within our health care systems and is exposing the pernicious implications of provider burnout,” says coauthor Farzan Sasangohar, assistant professor in the department of industrial and systems engineering at Texas A&M University.

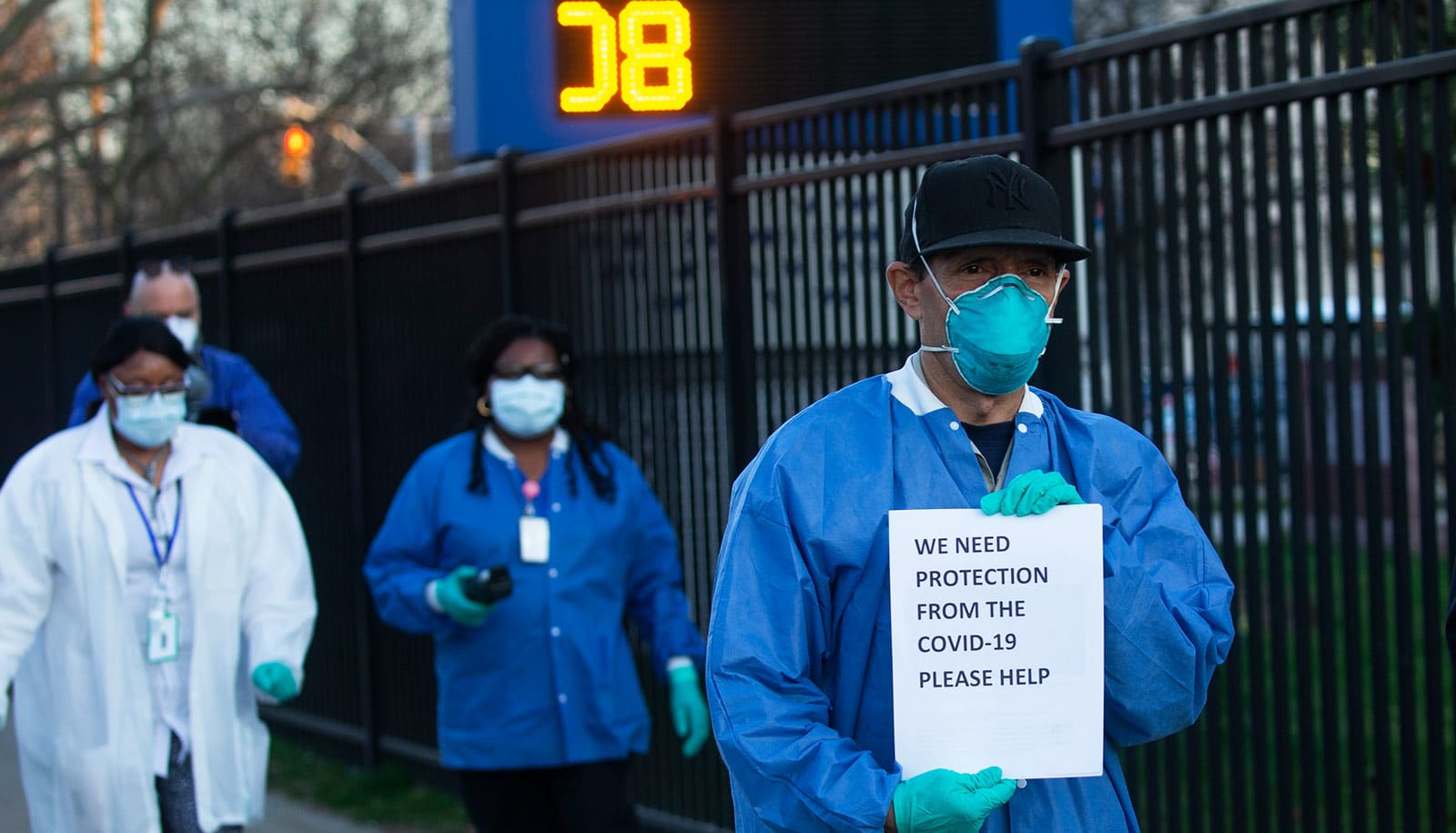

Health care workers are experiencing added stress from multiple areas. Many of them are working longer shifts and experiencing more deaths. The lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) and training on how to use new equipment causes many professionals to question if they have been exposed. This leads to fear that they could infect their family and loved ones.

In addition to those fears, there is anxiety surrounding job security. To reduce the spread of infection, many states have stopped elective procedures and consequently, employers have laid off many health care professionals or reduced their hours.

Four areas of stress

Sasangohar and the research team documented four major areas of stress with the goal of identifying mitigation strategies to reduce burnout among these life-saving workers. The four areas identified by the researchers include occupational hazards, national versus locally scaled responses, process inefficiencies, and financial instability.

Health care workers need effective PPE readily accessible and available to ensure their safety and that of their patients. Getting the necessary equipment has been challenging due to the low numbers of PPE and ventilators in the US Strategic National Stockpile and delays getting equipment into local areas. This slow response, which has caused some providers to reuse PPE past the point of safety and warranty protections, can contribute to anxiety in providers.

“Minimizing occupational hazard is the most important criteria to assure that our health care workforce is fully equipped and assured to be safe in order to face the battle against this virus,” says Bita Kash, professor of health policy and management in the Texas A&M School of Public Health and director of the Joint Center for Outcomes Research at Houston Methodist Hospital.

The process to secure assistance from federal authorities has been cumbersome and slow for providers. Many requests for additional ventilators and PPE are not being met. These uncertainties about when assistance will arrive has resulted in widespread anxiety among providers.

Process inefficiencies have also contributed to fatigue and burnout due to misinformation or conflicting information given between different specialties. While one subspecialty’s professional organization recommends a certain guideline, another specialty could recommend something else, which leads to confusion.

Anxiety and worry about future career prospects and the overall economy can also lead to provider burnout. Elective surgeries have been canceled or delayed, causing financial stress on some physicians. Others not directly affected by financial hardship may be worried about loved ones or their own family and how they will weather a coming economic recession.

What would ease burnout for doctors and nurses?

To reduce provider burnout and fatigue, the researchers recommend:

- Pandemic plans should include guidance for relevant industries to quickly transition into producing needed medical supplies

- National and regional disaster mitigation plans to help shorten the time needed to provide necessary equipment and testing

- Provision of adequate numbers of test kits and PPE

- Training on disaster management and response for medical professionals

- Relaxing licensing restrictions for individuals licensed outside their state of residence

- Creating a medical reserve corps of these licensed individuals

- Using wearable sensors to monitor health care workers’ mental health and provide simple ways to mitigate anxiety and stress.

“There is much to learn from the response to COVID-19,” says Sasangohar. The team was able “to learn not just from failures and shortcomings, but also from successful adaptations and improvised interventions at the individual, team, and system levels to improve our resilience.”

Source: Alexandra H. Salazar for Texas A&M University