A team of researchers propose using the James Webb Space Telescope to look at five planets in the Venus Zone, a search that could reveal valuable insights into Earth’s future.

Venus floats in a nest of sulfuric acid clouds, has no water, and its surface temperatures are hot enough to melt lead. Despite being such a scorching wasteland, however, the planet is often referred to as Earth’s sister because of similarities in size, mass, density, and volume.

Earth and Venus, which both formed about 4.5 billion years ago, now sit on opposite ends of habitability. This leaves astronomers with a giant question: Is Venus Earth’s past or Earth’s future?

“It’s all about trying to understand why Earth and Venus are so different now,” says Jim Head, a professor of geological sciences at Brown University. “We have Venus to look at here, but there are solar systems out there in which we can actually compare all these different things that we want to know. It’s a whole new parameter of space to explore.”

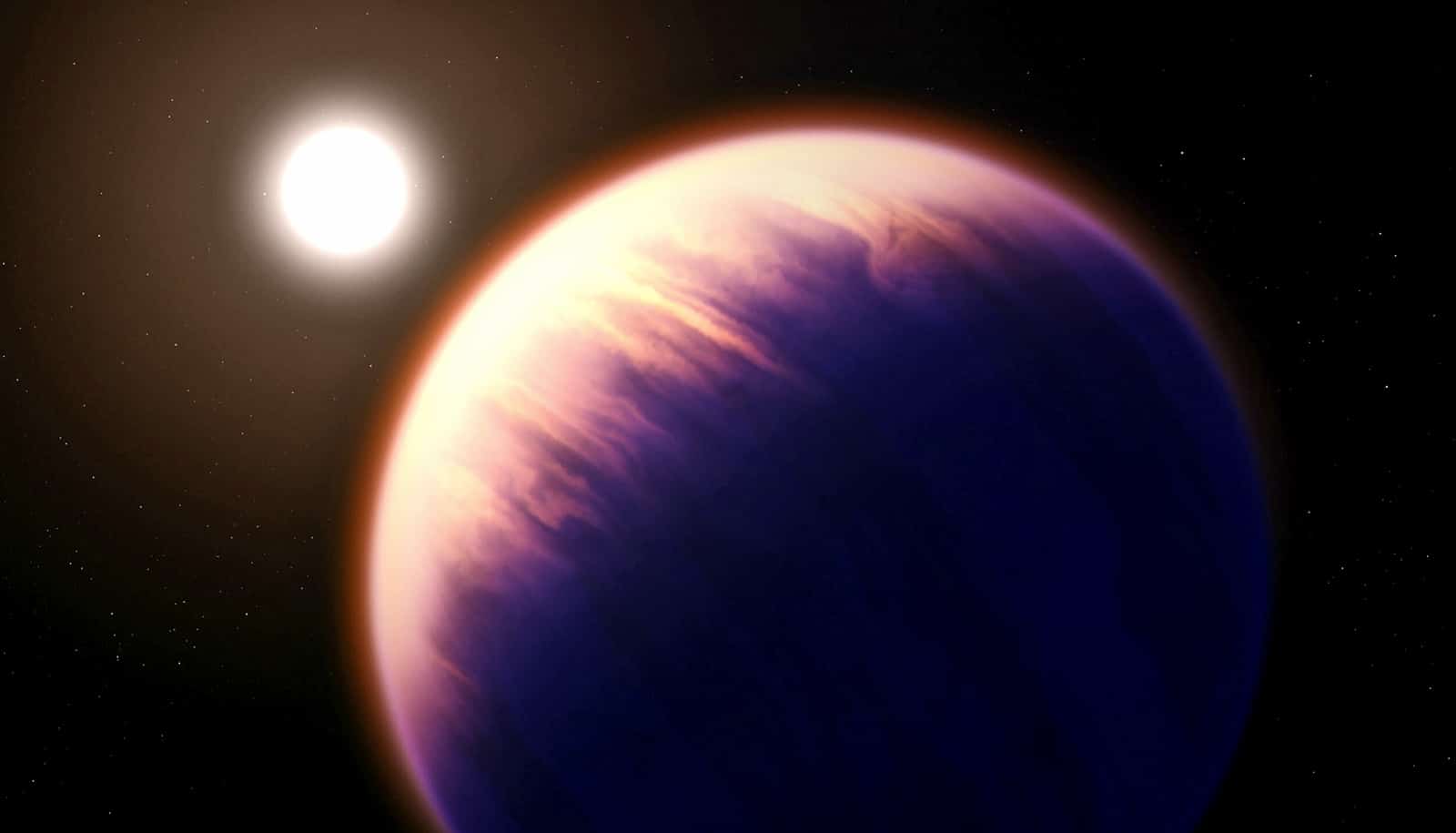

In the study in the Astronomical Journal, Held and colleagues identify five Venus-like planets from a list of more than 300. The researchers selected these terrestrial planets orbiting other stars, called exoplanets, because they were the most likely to resemble Venus in terms of their radii, masses, densities, the shapes of their orbits, and distances from their stars.

The researchers rank the Venus-like planets depending on the brightness of the stars they orbit to increase the odds that the Webb Telescope gets the clearest view of them, enabling researchers to pull key signals from them regarding the composition of their atmospheres.

The five planets all orbit regions called the Venus Zone, which was coined by astrophysicist and study coauthor Stephen Kane from the University of California, Riverside.

The Venus Zone encompasses the region around a star where it’s too hot for a planet to have water but not too hot for it to have no atmosphere. It is similar to the concept of a habitable zone, which is a region around a star where liquid surface water could exist.

The researchers propose the planets identified in the paper as targets for the Webb telescope in 2024. Webb is NASA’s most ambitious telescope to date and is enabling scientists not only to look into the deep past of the universe but to peer into the atmospheres of exoplanets for telltale signs of what the planet is like.

Studying exoplanets in the Venus Zone could give astronomers a better understanding of whether Venus was ever habitable. The Webb observations the researchers propose, for example, may reveal biosignature gases in the atmosphere such as methane, methyl bromide, or nitrous oxide, which could signal the presence of life. The researchers also hope to see through the observations whether Venus’s lack of plate tectonics is common and whether the planet’s volcanic activity is normal.

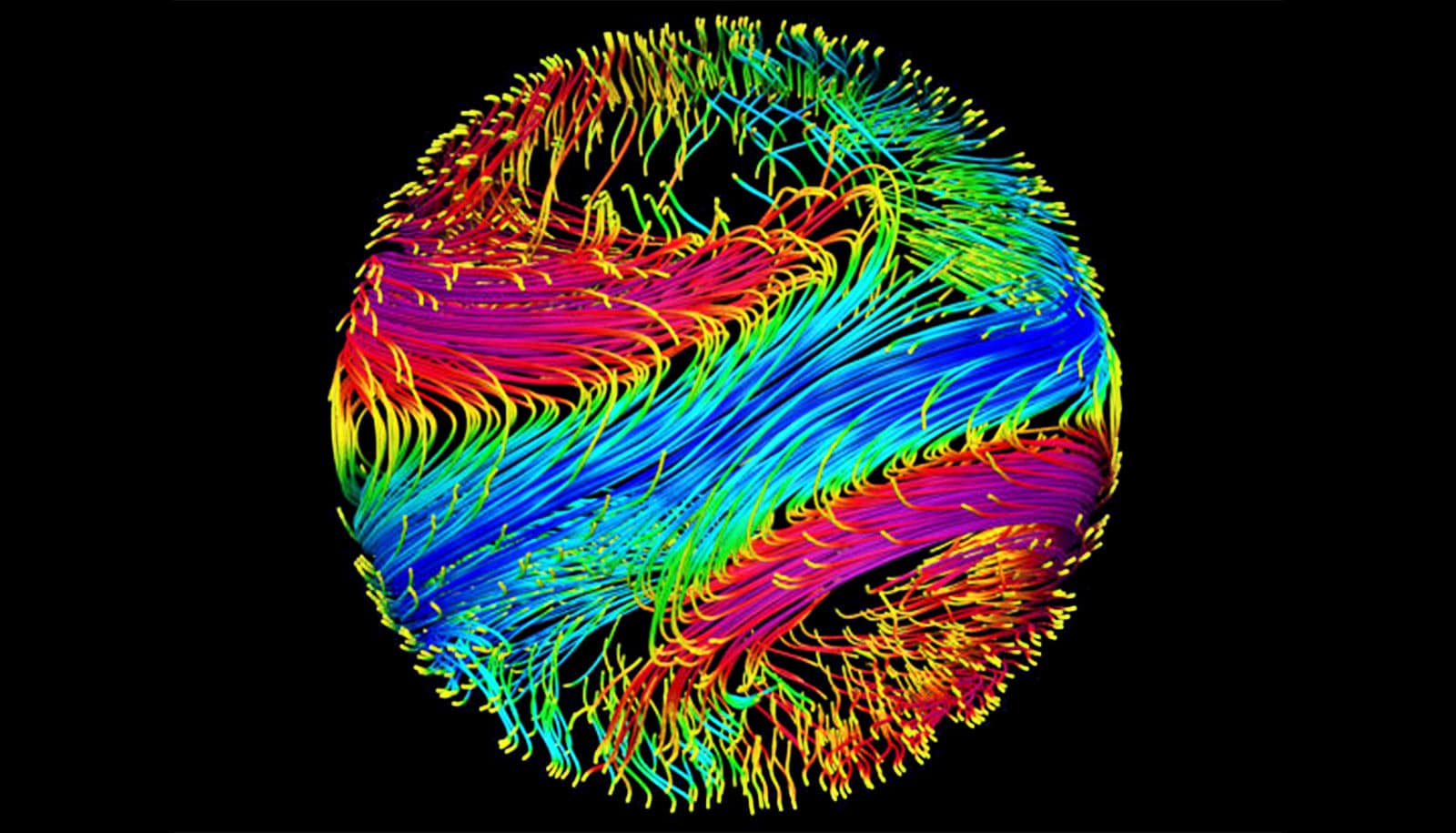

These observations will be complemented by NASA’s two upcoming spacecraft missions to Venus. The DAVINCI mission will measure gases in the Venusian atmosphere. The VERITAS mission will enable 3D reconstructions of the landscape.

Combined, the findings will help lead to a better understanding of the Earth-Venus divergence, which could serve as a dire warning for where Earth is heading, the researchers say.

Colby Ostberg, a UC Riverside PhD student, is the study’s lead author. NASA’s Habitable Worlds Program supported the work.

Source: Brown University