Climate change triggered by massive volcanic eruptions may have ultimately set the stage for the dinosaur extinction, a new study suggests.

The findings challenge the traditional narrative that a meteorite plummeting to Earth alone delivered the final blow to the ancient giants.

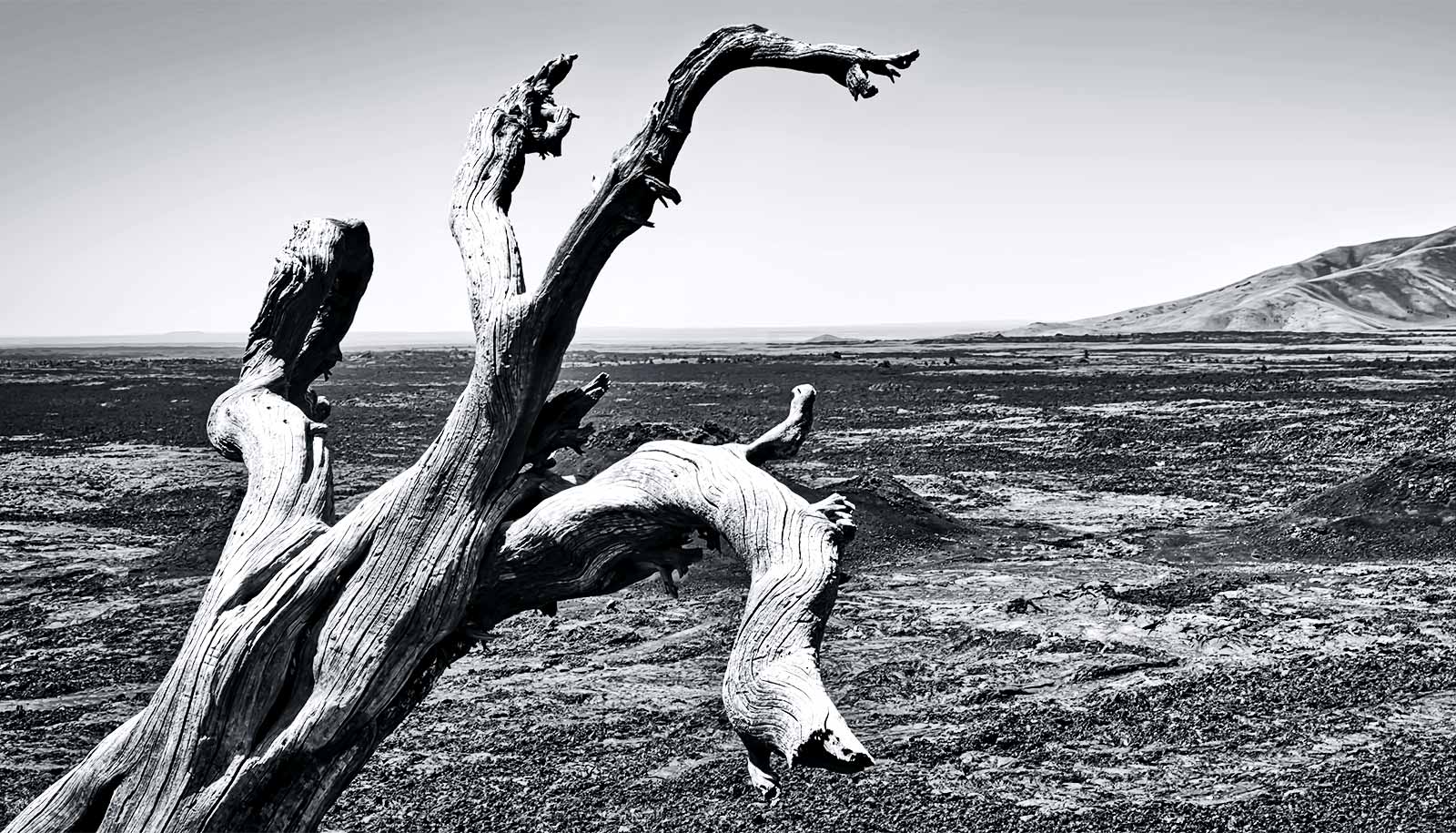

For the study in Science Advances, researchers from McGill University delved into volcanic eruptions of the Deccan Traps—a vast and rugged plateau in Western India formed by molten lava. Erupting a staggering one million cubic kilometers of rock, it may have played a key role in cooling the global climate around 65 million years ago.

The work took researchers around the world, from hammering out rocks in the Deccan Traps to analyzing the samples in England and Sweden.

In the lab, the scientists estimated how much sulfur and fluorine was injected into the atmosphere by massive volcanic eruptions in the 200,000 years before the dinosaur extinction.

Remarkably, they found the sulfur release could have triggered a global drop in temperature around the world—a phenomenon known as a volcanic winter.

“Our research demonstrates that climatic conditions were almost certainly unstable, with repeated volcanic winters that could have lasted decades, prior to the extinction of the dinosaurs,” says Don Baker, a professor in McGill University’s Earth and planetary sciences department.

“This instability would have made life difficult for all plants and animals and set the stage for the dinosaur extinction event. Thus our work helps explain this significant extinction event that led to the rise of mammals and the evolution of our species.”

Uncovering clues within ancient rock samples was no small feat. In fact, a new technique developed at McGill helped decode the volcanic history.

The technique for estimating sulfur and fluorine releases—a complex combination of chemistry and experiments—is a bit like cooking pasta.

“Imagine making pasta at home. You boil the water, add salt, and then the pasta. Some of the salt from the water goes into the pasta, but not much of it,” Baker says.

Similarly, some elements become trapped in minerals as they cool following a volcanic eruption. Just as you could calculate salt concentrations in the water that cooked the pasta from analyzing salt in the pasta itself, the new technique allowed scientists to measure sulfur and fluorine in rock samples. With this information, the scientists could calculate the amount of these gases released during the eruptions.

The findings mark a step forward in piecing together Earth’s ancient secrets and pave the way for a more informed approach to our own changing climate.

Source: McGill University