Earth’s ancient oceans likely contained much more salt than they do today, scientists say.

The finding may clarify how its life, atmosphere, and climate evolved.

In a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers suggest that for the first 500 million years of Earth’s existence, its oceans may have contained a salt level as high as 7.5%. Today’s oceans, by comparison, are about 2.5% salt.

Previous estimates for salinity of the early oceans, all based on indirect data, ranged from the current level to 10 times higher.

“This is just the beginning of deciphering the chemistry of the early ocean, as there are many other unknowns, but now we have a solid foundation to build upon,” says Jun Korenaga, professor of earth & planetary sciences at Yale University.

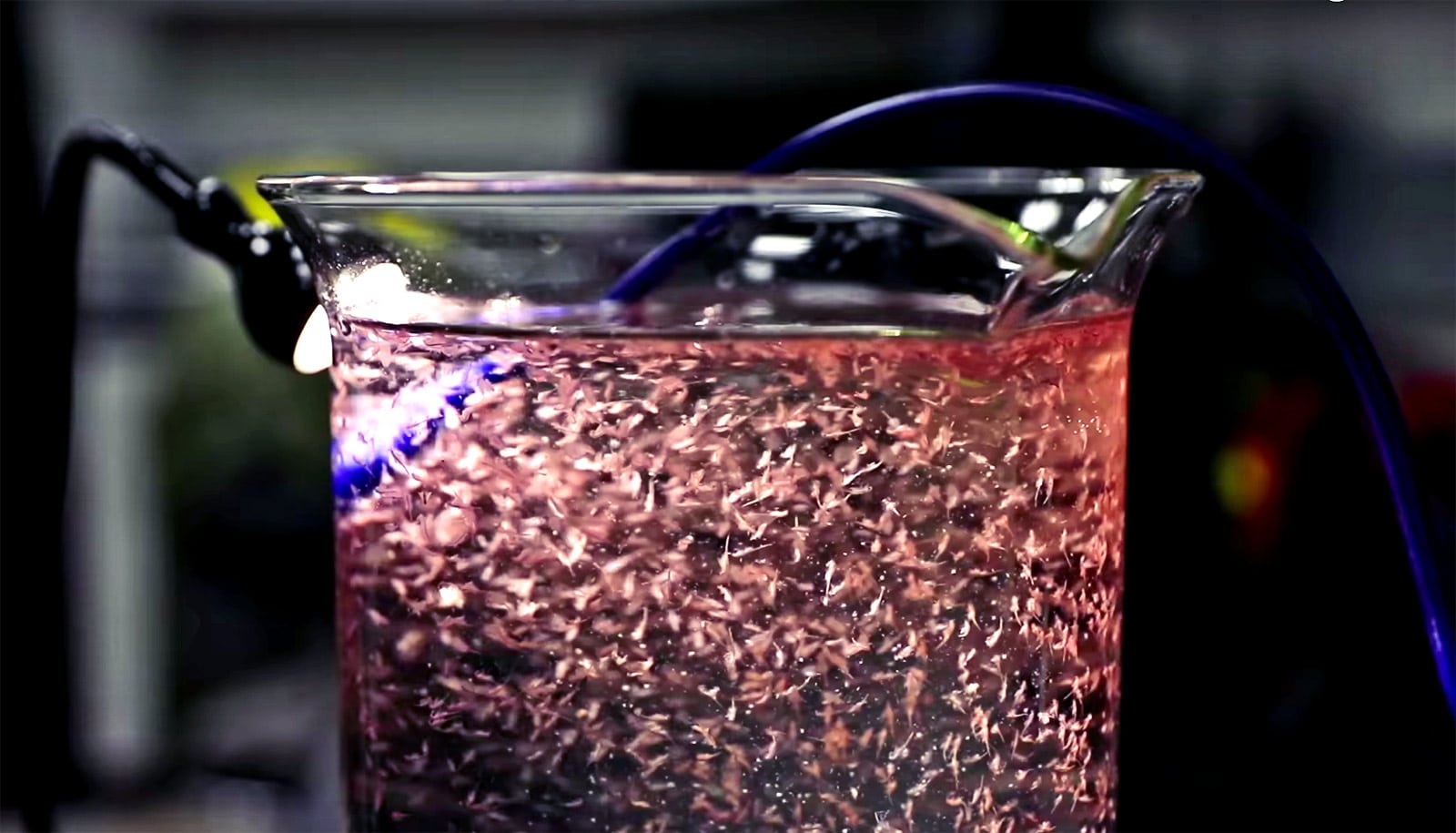

Korenaga and graduate student Meng Guo began their research with a broader, more fundamental question in mind. They wanted to know how much stable halogen material—elements such as fluorine, chlorine (found in salt), bromine, and iodine that, when they react with metals, produce a range of salts—exists on Earth.

Halogens play a critical role in some of the most basic processes related to the planet’s formation and evolution, including the way Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, and rocky mantle interact. The presence of halogens in seawater is particularly important, due to the essential nature of oceans in making life on Earth possible.

“Seawater chemistry dictates not only the acidity of the ocean, but also the way carbon dioxide is partitioned between the atmosphere and the ocean,” Guo says.

Until now, estimates for the global abundance of halogens have been based on an assumption that the ratio of certain elements in the crust and the mantle—Earth’s 3,000-kilometer-thick rocky layer—has remained constant throughout melting and crystallization, and these estimates have suggested that most halogens exist close to the surface.

Korenaga and Guo say that isn’t the case. They created a new method to estimate the global levels of halogens, based on a new algorithmic tool and the latest science about how other elements cycle through the Earth’s surface and interior layers.

Their new finding suggests that chloride and other halogens had largely been expelled from the planet’s interior during Earth’s first 500 million years—bringing them closer to Earth’s crusty surface and oceans—and then cycled most of them back into the mantle afterwards.

“Our finding is entirely opposite to the conventional wisdom,” Korenaga says.

The National Science Foundation and NASA supported the research.

Source: Yale University