In a new study, researchers examined how pairs of freely moving macaques interacting in a naturalistic setting use visual cues to guide complex, goal-oriented cooperative behavior.

Eye contact and body language are critical in social interaction, but exactly how the brain uses this information in order to inform behavior in real time is not well understood.

The study in Nature offers first evidence that the part of the brain that processes visual information—the visual cortex—plays an active role in social behavior by providing an executive area—the prefrontal cortex—with the signals necessary to generate the decision to cooperate.

The researchers used a combination of behavioral and wireless eye tracking and neural monitoring to study the macaques.

“We are the first to use telemetric devices to record neural activity from multiple cortical populations in the visual and prefrontal cortex while animals explore their environment and interact with one another,” says Valentin Dragoi, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Rice University and the distinguished chair in neuroprosthetics at Houston Methodist. “When primates, including humans, interact, we make eye contact and use body language to indicate to conspecifics what we want to do.

“Until now, we didn’t know how what we are looking at guides our decision to cooperate or not, because of our inability to measure oculomotor events and correlate them with what neurons are doing in that instant. Because the technology was not there, that knowledge was just unattainable.”

Most of what neuroscience has learned about the neural underpinnings of cognition originated from studies in which animals were restrained and performing a task in isolation in response to artificial stimuli on a computer screen rather than during actual interaction with peers in a more naturalistic environment. The ability to track neural activity as animals move and behave freely represents a significant step forward in neuroscience research and promises to shed new light on the inner workings of the brain.

“This has been the golden dream of neuroscientists for a long time—to record from neurons on the fly while the animal is free-moving,” says Dragoi, who also serves as scientific director of the Center for Neural Systems Restoration, a joint Houston Methodist-Rice venture dedicated to neuroscience research and treatment innovation. “We tracked populations of neurons in the visual cortex ⎯ the part of the brain that extracts information about vision—and the prefrontal cortex—an executive area that encodes our decision to carry out certain actions.”

In the experiment, the researchers observed two pairs of macaques over the course of several weeks as they learned to work together for food reward. Each trial had the monkeys moving freely about an enclosure, separated by a clear divider. The monkeys had previously learned that pressing a button causes a snack tray to come within reach, but during trials, this only happened if the animals pressed the button simultaneously. As the macaques’ cooperation skills improved, the frequency with which they scoped out socially relevant cues—their partner, the snack tray—was found to increase prior to their acting in concert.

“This technology allows us to differentiate between active and passive vision,” Dragoi says. “Active vision is when we act on a stimulus we’re looking at with a purpose in mind. When I’m engaged in social interaction, I’m acting in some way, extracting visual information and using that information to cooperate. Our main finding is getting to see how sensory neuron populations extract information, transmit it to an executive area, and how they synchronize in real time to underlie the decision to cooperate.”

Both Dragoi and Behnaam Aazhang, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, emphasize the critical contributions of Melissa Franch, lead author on the study, a former PhD student in Dragoi’s lab and now a postdoctoral researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, and Sudha Yellapantula, a Rice doctoral alumna of Aazhang’s group who is now working as a research professional in the health care industry.

“They deserve a lot of credit,” says Aazhang, who also serves as director of the Rice Neuroengineering Initiative and codirector of the Center for Neural Systems Restoration.

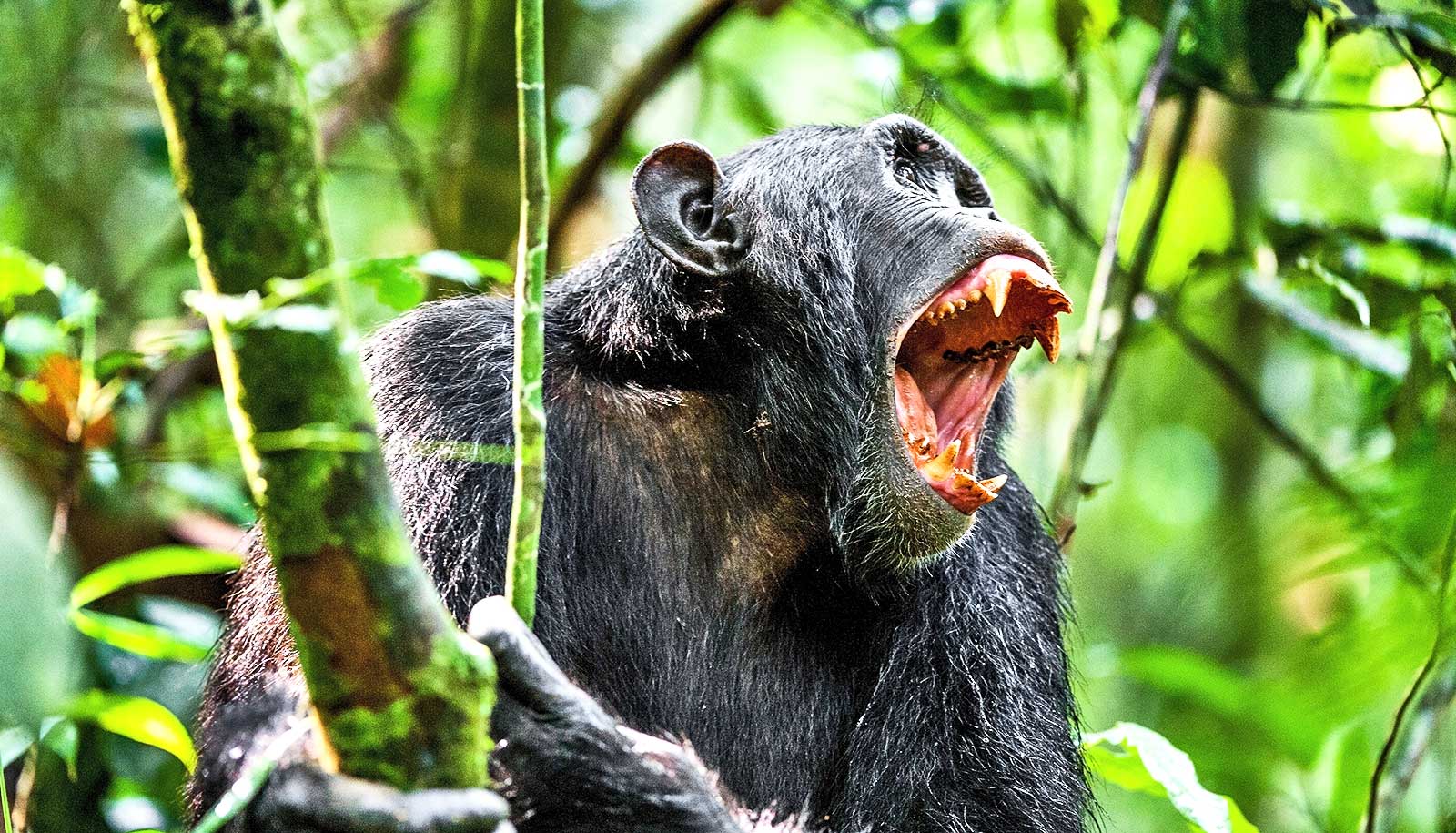

“This work is very interdisciplinary and involves a complex experimental design intended to test the hypothesis that the visual frontal cortex has an important role in social behavior,” Aazhang adds. “Many animals are not very social, but primates are, which was an important factor in the research, given the nature of the hypothesis.”

It turns out that expressions like “staring daggers” and “seeing eye-to-eye” are more than just a quirk of the English language: We now have evidence that the visual cortex and the prefrontal cortex work in concert to achieve complex behaviors like cooperation.

Support for the research came from the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Rice University