Researchers have come up with a missing math formula to measure the viscosity of the droplets like those that aircraft spray over farm fields.

Drones and other aircraft effectively spray pesticides over miles of crops, but the method also can pollute the environment if wind carries the mist off-target.

The discovery ends a decades-long race by researchers around the world to make surface viscosity measurable

One of the problems is that tiny droplets are hard for aerial crop sprayers, inkjet printers, and a wide range of other machines to control.

The researchers are the first to come up with the math formula that could change that.

“There are many properties that affect how a droplet forms. One of those important properties is surface viscosity, which people have had a heck of a time trying to measure because they just didn’t have the tools to do it,” says Osman Basaran, a professor of chemical engineering at Purdue University.

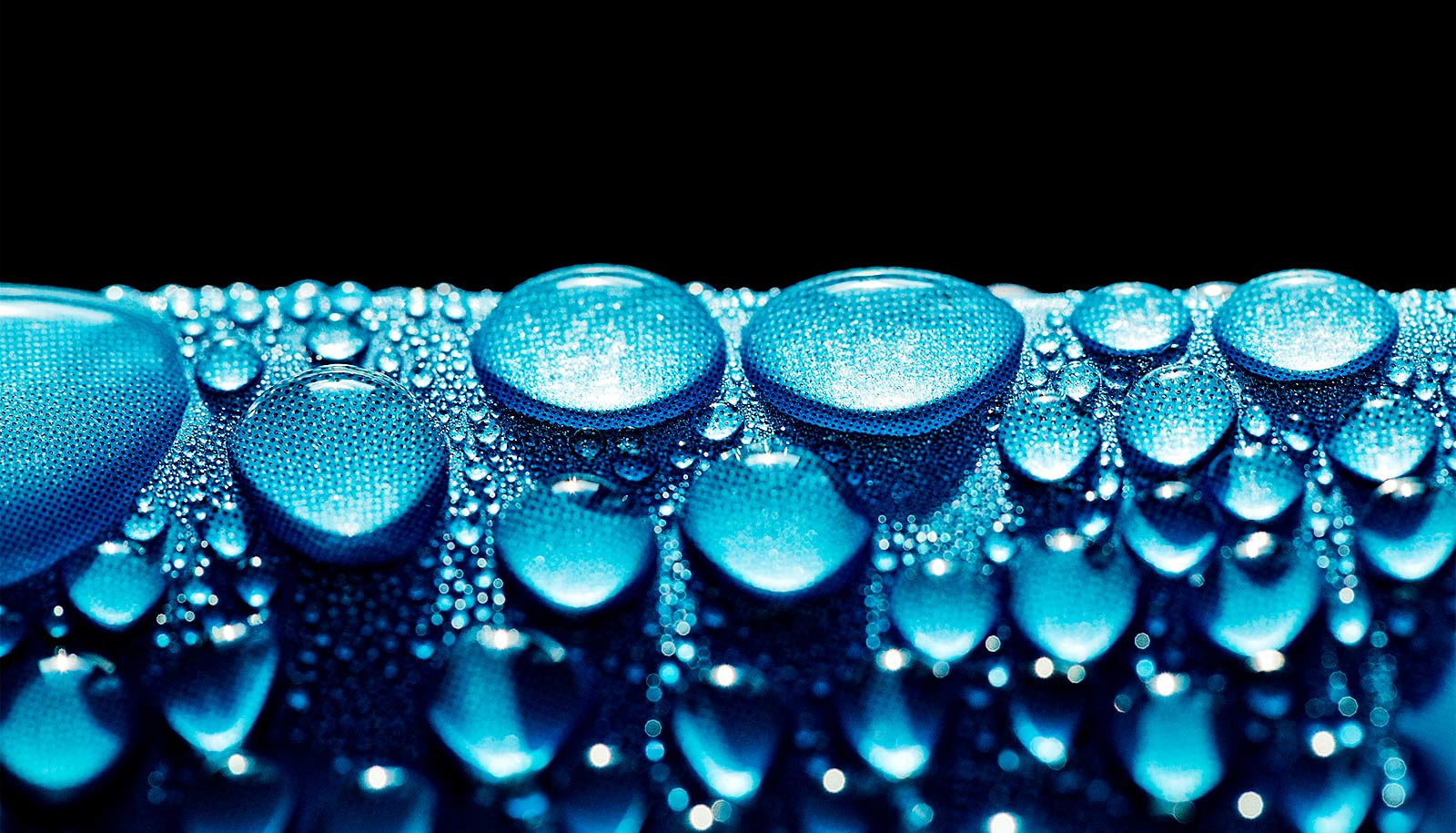

Pesticides and other chemicals contain additives called surfactants. These surfactant molecules resist each other at a liquid’s surface, giving rise to a sticky force called surface viscosity that can make the droplet smaller. The higher the surface viscosity, the more compact a droplet’s shape.

The researchers have figured out a way to calculate surface viscosity just by looking at how a droplet stretches. A picture taken of the stretched droplet as it starts to break gives the values to put into a simple math formula that provides the surface viscosity measurement.

The discovery ends a decades-long race by researchers around the world to make surface viscosity measurable.

Not being able to measure exactly how much surface viscosity affects drop formation has put limits on making machines safer and more precise, says Basaran, who directs a center that works to resolve the science behind problems in manufacturing machinery.

A better understanding of droplets and how to control them affects industries such as agriculture, health care, and energy. Like crop spraying, inkjet printing in a factory produces tiny droplets that can get into the air and cause breathing problems.

More precise control of a liquid-like substance also could enhance a machine’s performance, such as giving a 3D printer the ability to produce more reliable or detailed objects.

“A material with too high or too low surface viscosity can lead to bad outcomes in the manufacturing process. Knowing those measurements allows you to use different chemistries to make a material that doesn’t lead to a surface viscosity that’s going to result in a bad outcome,” Basaran says.

Next, Basaran’s team plans to incorporate this math formula into experiments for recommending new machine designs. The formula could also become a commercial instrument in the future, such as a smartphone app.

“This discovery opens up a lot of avenues for basic research that just weren’t possible before,” Basaran says.

The research appears in Physical Review Letters.

Source: Purdue University