A new metal structure is so water repellent that it refuses to sink—no matter how often it’s forced into water or how much it’s damaged or punctured.

Could this lead to an unsinkable ship? A wearable flotation device that will still float after a puncture? Electronic monitoring devices that can survive in long term in the ocean?

All of the above, says Chunlei Guo, professor of optics and physics at the University of Rochester.

Spider ‘bells’ and ant ‘rafts’

The structure, inspired by diving bell spiders and rafts of fire ants, uses a groundbreaking technique the lab developed for using femtosecond bursts of lasers to “etch” the surfaces of metals with intricate micro- and nanoscale patterns that trap air and make the surfaces superhydrophobic, or water repellent.

Enter the spiders and fire ants, which can survive long periods under or on the surface of water. How? By trapping air in an enclosed area.

Argyroneta aquatic spiders, for example, create an underwater dome-shaped web—a so-called diving bell— that they fill with air carried from the surface between their super-hydrophobic legs and abdomens. Similarly, fire ants can form a raft by trapping air among their superhydrophobic bodies.

“That was a very interesting inspiration,” Guo says. As the researchers note in the paper: “The key insight is that multifaceted superhydrophobic (SH) surfaces can trap a large air volume, which points towards the possibility of using SH surfaces to create buoyant devices.”

Unsinkable metal structure

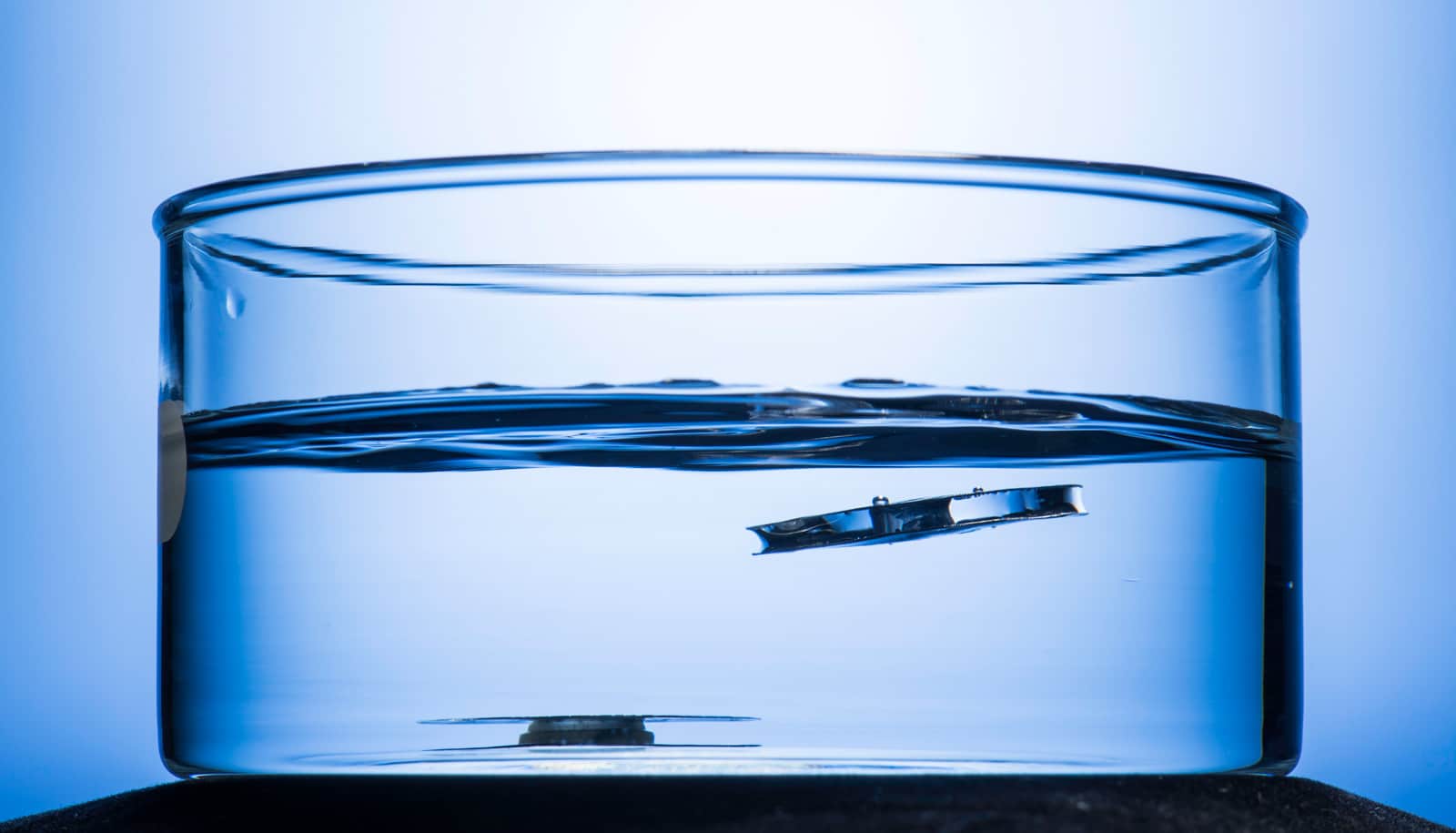

Guo’s lab created a structure in which the treated surfaces on two parallel aluminum plates face inward, not outward, so they are enclosed and free from external wear and abrasion. Just the right distance to trap and hold enough air separate the surfaces to keep the structure floating—in essence creating a waterproof compartment.

Even after researchers forced the structures to submerge for two months, they immediately bounced back to the surface after the load released, Guo says. The structures also retained this ability even researchers punctured them multiple times, because air remains trapped in remaining parts of the compartment or adjoining structures.

Etch other metals

Though the team used aluminum for this project, the “etching process “could be used for literally any metals, or other materials,” Guo says.

When the Guo lab first demonstrated the etching technique, it took an hour to pattern a one-inch-by-one-inch area of surface. Now, using lasers seven times as powerful, and faster scanning, the lab has sped up the process, making it more feasible for scaling up for commercial applications.

The paper appears in ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces. Additional coauthors are from the University of Rochester and the Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics, and Physics in China.

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the US Army Research Office, and National Science Foundation funded the work.

Source: University of Rochester