Tyrannosaurus rex, one of the largest meat-eating dinosaurs on the planet, had an “air conditioner” in its head, according to new research.

In the past, scientists believed two large holes in the roof of a T. rex’s skull—called the dorsotemporal fenestra—were filled with muscles that assist with jaw movements.

But that assertion puzzled lead researcher Casey Holliday, a professor of anatomy in the School of Medicine at the University of Missouri.

“It’s really weird for a muscle to come up from the jaw, make a 90-degree turn, and go along the roof of the skull,” Holliday says. “Yet, we now have a lot of compelling evidence for blood vessels in this area, based on our work with alligators and other reptiles.”

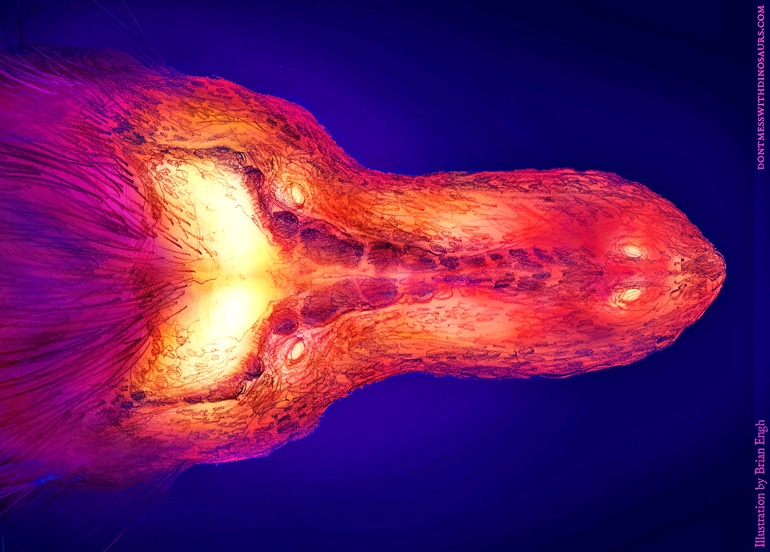

Using thermal imaging—devices that translate heat into visible light—researchers examined alligators at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park in Florida. They believe their evidence offers a new theory and insight into the anatomy of a T. rex head.

An alligator’s body heat depends on its environment. The researchers found when alligators are trying to cool off, the holes in the roof of their skulls were dark, like they were turned off.

“An alligator’s body heat depends on its environment,” says Kent Vliet, coordinator of laboratories at biology department at the University of Florida. “Therefore, we noticed when it was cooler and the alligators are trying to warm up, our thermal imaging showed big hot spots in these holes in the roof of their skull, indicating a rise in temperature. Yet, later in the day when it’s warmer, the holes appear dark, like they were turned off to keep cool. This is consistent with prior evidence that alligators have a cross-current circulatory system—or an internal thermostat, so to speak.”

Thermal imaging—devices that translate heat into visible light—allowed researchers to capture the body heat of alligators at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park in Florida.

Holliday and his team took their thermal imaging data and examined fossilized remains of dinosaurs and crocodiles to see how this hole in the skull changed over time.

“We know that, similarly to the T. rex, alligators have holes on the roof of their skulls, and they are filled with blood vessels,” says Larry Witmer, professor of anatomy at the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine at Ohio University.

“Yet, for over 100 years we’ve been putting muscles into a similar space with dinosaurs. By using some anatomy and physiology of current animals, we can show that we can overturn those early hypotheses about the anatomy of this part of the T. rex’s skull.”

The study appears in The Anatomical Record. Additional coauthors on the study are from Ohio University.

Funding for the research came from the Jurassic Foundation, the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Richard Estes Memorial Grant, Ohio University, an SEC Visiting Faculty Travel Grant, a Richard Wallace Faculty Incentive Grant, the National Science Foundation, and the University of Missouri. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Source: University of Missouri