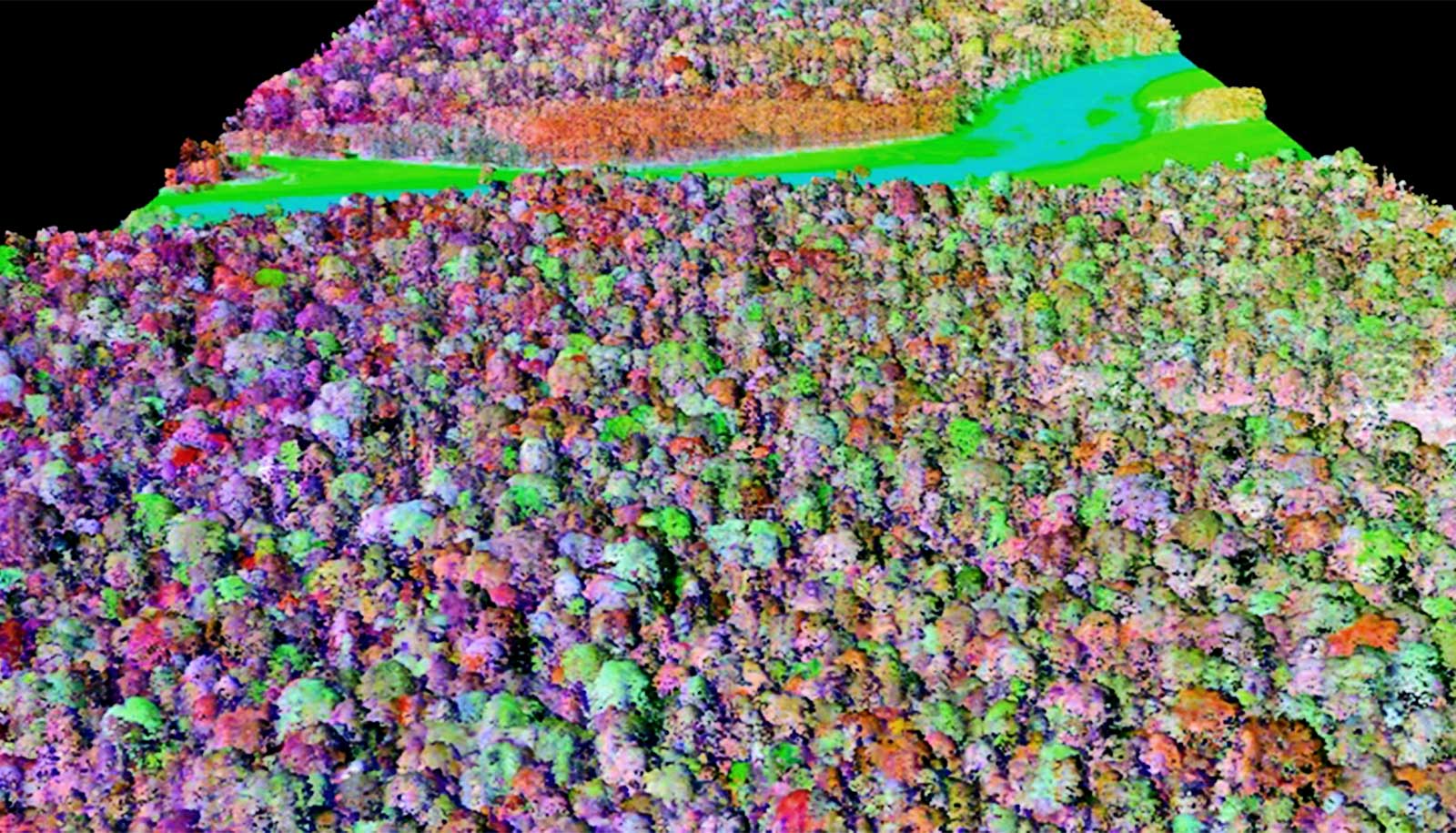

Researchers have used remote sensing to measure plant biodiversity from the Amazon basin to the Andes Mountains in Peru to better understand how tropical forests will respond to climate change.

The researchers used Arizona State University’s Global Airborne Observatory, or GAO, to show that combining traditional on-the-ground field measurements of carbon with aerial measurements of plant chemistry can improve the ability to model and predict the role that tropical forests play in the global carbon cycle.

“This work is important because it can be difficult to obtain measurements in some of these remote places,” says Sandra Durán, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Arizona.

“Climate scientists are interested in predicting how much carbon is able to be captured by specific forests. We’re showing that these measurements of plant chemistry taken from airplanes have potential to make predictions of carbon gain in one of the most biodiverse forests in the world for the first time.”

Traits such as nutrient concentrations and defense compounds in its leaves affects a tree’s ability to grow and survive. While researchers have measured these traits in trees located around the globe, incomplete data from the Andes’ highly diverse forests has made it difficult to understand how trees impact the functioning of tropical forests.

Durán and her collaborators utilized GAO maps of plant chemistry to quantify the diversity of plant chemistry that is not visible to the naked eye. The measurements allowed them to see how diversity can predict rates of carbon capture in tropical forests that contain a large range of temperatures and elevations.

“New technology is enabling us to see the functioning of the forest in a new light,” says coauthor Brian Enquist, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

“This technology creates a continuous map of the variation in plant chemistry, even in highly remote areas of the Earth that would be almost impossible to gather from ground surveys. This will improve our ability to model tree responses to environmental changes, from small plots to large regions.”

“Our plant canopy chemistry maps have been used for many purposes over the past 10 years, but this new application—to assess drivers of forest carbon cycling—is new and opens doors for the use of our mapping approach throughout the world’s tropical forests,” says coauthor Greg Asner, principal investigator of GAO.

The paper appears in Science Advances. Additional coauthors are from Oxford University; Arizona State University; Wake Forest University; Universidad Católica del Perú; Universidad Nacional de Córdoba; and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Funding for the came from the National Science Foundation.

Source: University of Arizona