For the first time, tissue donors in a pilot program will be able to anonymously track how scientists use their samples.

When a doctor took Henrietta Lacks’ cancer cells in 1951, it was without her knowledge. Neither she nor her family were informed about the subsequent use of her “immortal” cells in medical research around the world. Today, researchers cannot use patients’ tissues without permission, but patients never know what becomes of their samples.

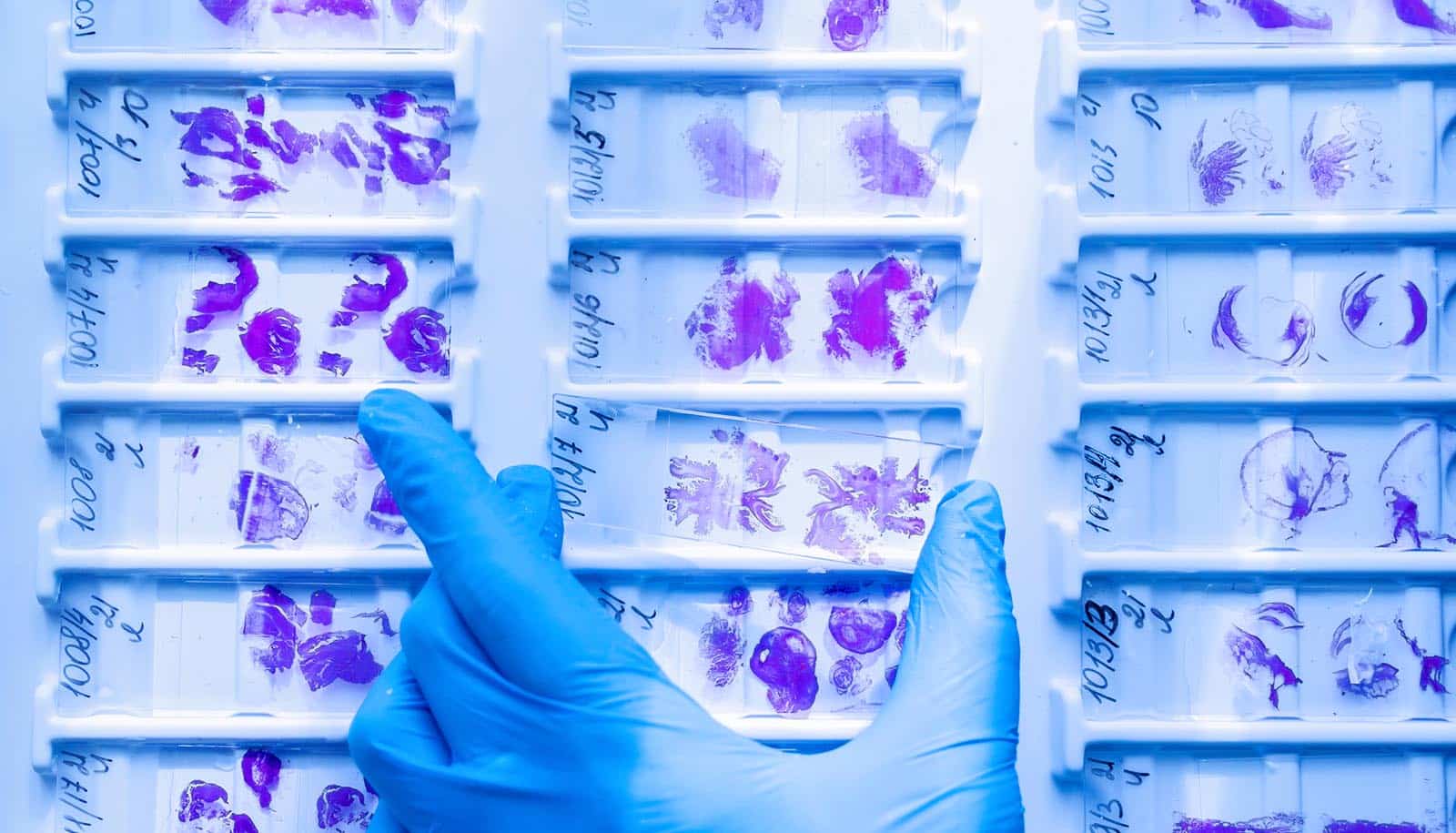

The pilot program will use blockchain technology to give every patient who consents to the use of their tissue samples for research at the University of Pittsburgh’s Breast Disease Research Repository the opportunity to track their use in perpetuity, while keeping their identities anonymous to the researchers.

“A healthcare system built on de-identification emphasizes privacy but sacrifices our duties of clinical care to patients,” says Jeffrey Kahn, director of the Berman Institute of Bioethics at Johns Hopkins University. “It limits the effectiveness of science and prevents any attempt to share the broader benefits of research discoveries with those who contribute to its success.”

Today’s standard of informed consent assures patients that their tissues cannot be used in medical research without a signed agreement and must be stripped of identifying details such as names and birth dates. But because of these well-intended privacy measures, individuals never know how their tissues are used, or by whom, nor do they know if they led to any discoveries.

The program will provide participants with a non-fungible token (NFT) that will allow them to follow their samples. NFTs are digital assets on a blockchain with unique identification codes and metadata that distinguish them from each other, while their owners’ identities remain encrypted. A blockchain is a shared, tamper-proof ledger that facilitates the decentralized recording of information that can be audited by computer code to prove ownership and permissions.

All patients who have consented to participate in the University of Pittsburgh’s Breast Disease Research Repository will be invited to be part of the project, says Marielle Gross, adjunct professor of bioethics at the Berman Institute and a women’s health physician at the University of Pittsburgh, adding that during its pre-pilot phase the first 20 patients contacted signed up within 24 hours.

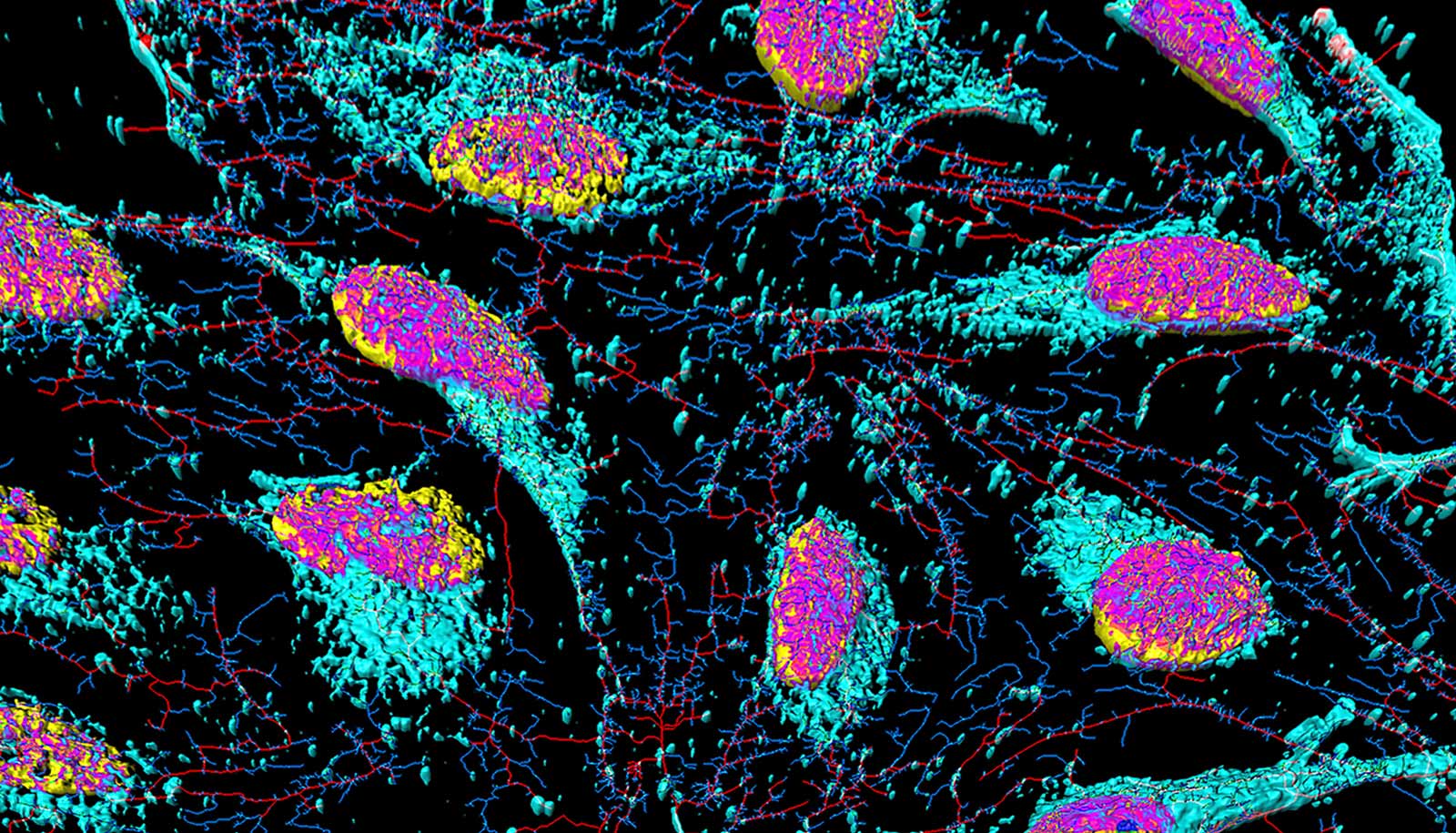

“NFTs and blockchain technology offer an innovative solution to reconnect individuals with their contributions to research, without compromising privacy or provenance. Bringing patients into the fold as true stakeholders in research allows for increased trust, transparency, and participation in biomedical research,” says Gross, adding that the blockchain technology could allow labs from across the country using the same donor’s samples to collaborate and share the results.

“Right now, there are researchers working in labs literally right next door to each other who aren’t aware they’re researching samples from the same individual,” says Gross. “This new approach to privacy-protecting tissue sharing can enable us to maintain patient confidentiality while simultaneously maximizing research benefits and unlocking the future of precision medicine.”

The project arose from work Gross initiated as a postdoctoral fellow at the Berman Institute and had funding from the Emerson Collective.

Gross has created a startup, heny, Inc., with Kahn’s support and ethical oversight, that seeks to use the blockchain technology to extend personalized biobank access to all research participants within and beyond the current pilot population.

Source: Johns Hopkins University