The 1905 story about the Chicago meatpacking industry that inspired Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle also shows the power of photojournalism, a study argues.

The research looks back at a series of early 20th-century articles in The Lancet, which British scientists, sanitarians, and physicians were reading. Journalist Adolphe Smith wrote the articles, which offered a shocking look at Chicago’s meatpacking industry. His articles laid a foundation for the better-known revelations of The Jungle, which followed a couple of years later.

Emily Kathryn Morgan, a photography historian and an assistant professor of art and visual culture at Iowa State University, looked at how Smith used both photos and text to prove his point “that animal health and worker health deeply affect public health.”

“The meat industry was much more inclined to allow photographers into their facilities well into the 20th century to help further their cause,” Morgan says. “People used to tour these packing companies and they weren’t upset by what they saw. It was really only when Smith, and then Sinclair, pointed out that they were eating adulterated products that people got grossed out.

“The same things happen today. People can see a lot of really horrifying images … but the biggest scandal is always the public health scandal.”

Smith’s series was one of the first uses of both text and photographs to serve as evidence “to expose a problematic situation to the light of general knowledge,” writes Morgan in the journal Food & History.

Chicago meatpacking

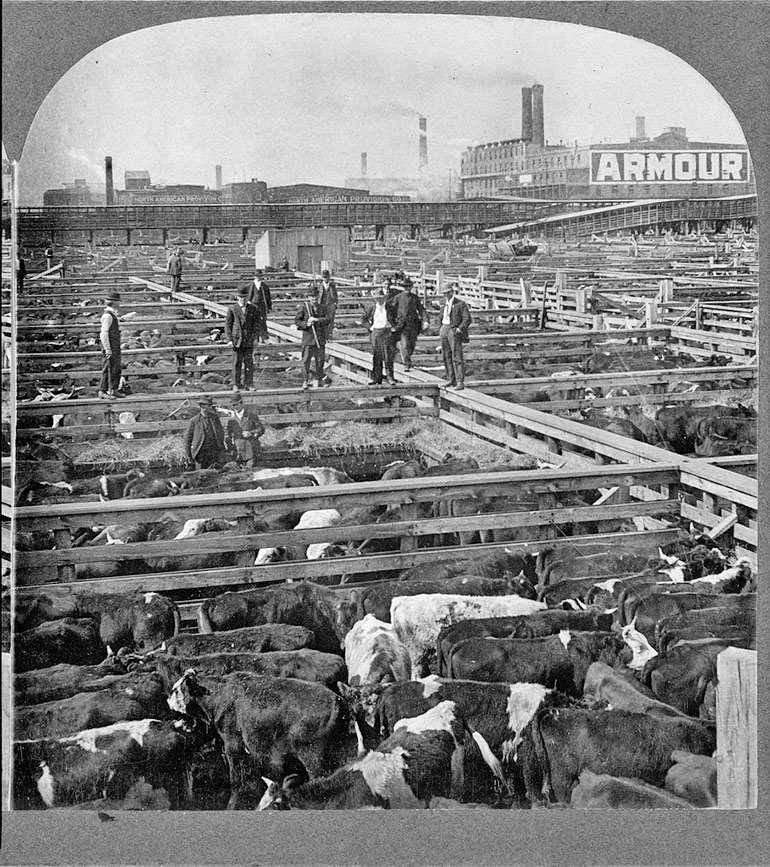

Chicago’s meatpacking district opened in 1865. With the innovation of refrigerated railroad cars, Chicago became a hub of meat processing as packing companies popped up around the stockyards. The area became known as Packingtown.

By the mid-1880s, Chicago was exporting meat overseas, primarily to British markets—which is how Smith became interested in Chicago’s meat industry and related public health issues.

Smith traveled to the US in 1904, heading to Chicago to explore how both animals and humans fared in Packingtown.

He found unsanitary conditions, inhumane treatment of hogs and cattle, and poor worker safety. Smith used photos to bring data and his descriptions to life: “Photos, printed alongside his articles, made his textual claims about public health more believable.”

Controversy and tinned meat

Smith’s Chicago articles, published in early 1905, had immediate effects. Morgan notes in her study that Chicago’s tinned meat exports dropped by 50% in the months following. American news media caught wind of the controversy, and by August 1905, new food-inspection protocols were in place in Packingtown.

Smith walked author Upton Sinclair through the packinghouses. That tour, combined with Smith’s articles, provided inspiration for The Jungle, Sinclair’s novel about the meat industry and working conditions at the time.

By 1906, The Jungle had further amplified the issue, leading to a government investigation, revamped food and public health policies, and then-President Theodore Roosevelt signing the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act—which led to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration.

In 1909, Smith returned to Chicago and reported that the packinghouses had improved.

He realized that photography could serve as both evidence and as a powerful tool of persuasion. The meatpacking companies recognized this, too, sending him photos of improved conditions.

This lightbulb moment led to an increased use of photography by companies to shape their public image, promote themselves, and celebrate industrialization—as well as by critics, who used photography to shed light on problems that should concern the public and enact change.

“We have a greater recognition today that photography creates a sense of immediacy, that it can convey impact,” Morgan says. “It can involve people more than just a written text, and photography in conjunction with text is much more powerful than either one on its own.”

Source: Iowa State University