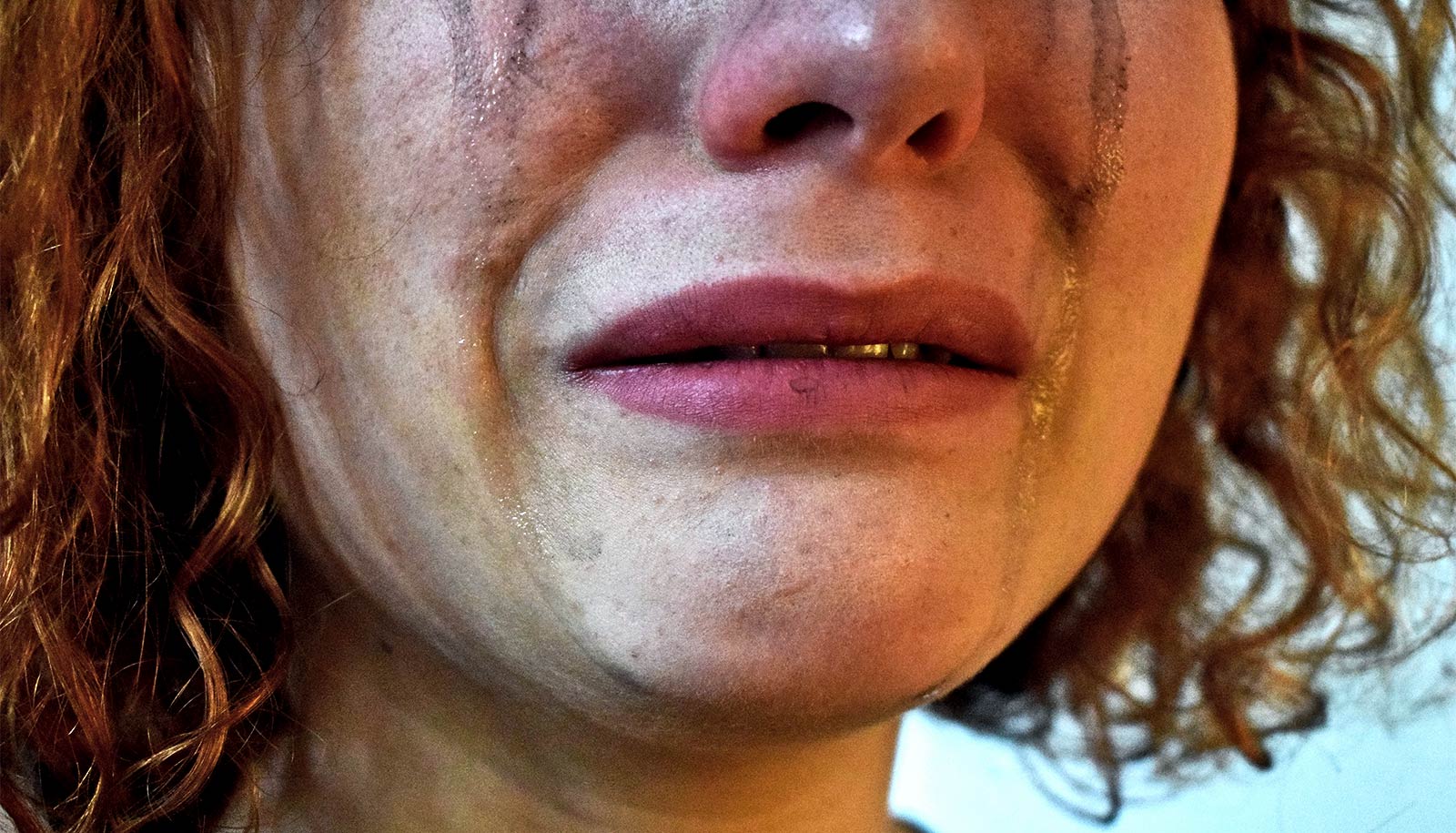

Losing a spouse can be a devastating experience for anyone, but the death of a spouse from COVID-19 may be worse for mental health than deaths from other causes, a new study shows.

While there were strong associations between the recent death of a spouse and poorer mental health both before and during the pandemic, people who lost a spouse to COVID-19 were more likely to report symptoms of depression and loneliness than comparable people whose spouses died just before the pandemic began.

The findings underscore the ongoing health risks posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, even to those who have not been infected by the virus, says Ashton Verdery, a professor of sociology, demography, and social data analytics at Penn State.

“These risks apply to millions of people across the globe who have lost their wives, husbands, and partners,” Verdery says. “Along with evidence that suggests those who experience the highest rates of mental health problems after the death of a spouse also face the largest risks of subsequent physical health problems, our study underscores the potentially significant health ramifications to those losing loved ones to the pandemic.”

The findings, published in the Journals of Gerontology-Series B, could help inform policy and suggest a need for extra clinical attention to those who have recently lost loved ones to COVID-19, Verdery says.

Previous research from Verdery and his team estimated that 8.8 million individuals lost close family members to COVID-19 by April 2022. Additionally, “bereavement“—the experience of recently losing a friend or family member—has been shown to have poor effects on health.

But while losing a spouse, in particular, has been linked with an increased risk for mental health problems and declines in physical health, Verdery says less was known about whether losing a spouse in a traumatic event such as a pandemic posed higher risks than usual.

“Other studies have found that when a person experiences a sudden or traumatic ‘bad death’—characterized by such factors as greater pain, social isolation, and psychological distress—it can be harder on their loved ones, who then go on to face elevated health risks of their own,” Verdery says. “Given the enormity of the impact of the pandemic, we wanted to see whether this effect applied to those who lost a spouse to COVID-19.”

For the study, the researchers analyzed data from 27 countries during two different time periods: before the pandemic, from October 2019 to March 2020; and early in the pandemic, from June to August 2020.

Data included information on mental health, including the participants reporting their feelings of depression, loneliness, and trouble sleeping. Data was also gathered about whether participants had recently lost a spouse, when the death occurred, and whether the death was due to COVID-19.

While the study specifically explored the effects of losing a spouse, the researchers say they believe the findings could extend to other deaths experienced during the pandemic, even if they were not as a result of COVID-19.

“Many deaths during the pandemic likely became more traumatic for their loved ones due to fear of seeking medical care and hospitals restricting friends and family from visiting patients, all which likely made it difficult for people to process deaths regardless of its specific cause,” Verdery says.

“Grieving and mourning were also complicated during the pandemic due to social isolation, along with other stressors such as financial insecurity and lack of practical and emotional support, all of which could further aggravate emotional distress.”

The researchers say in the future, additional research could explore whether other types of bereavement during the pandemic—such as children losing their parents—carry similar additional risks.

Additional coauthors are from Purdue University, the University of Southern California, the University of Western Ontario, and Penn State.

The National Institute on Aging and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development helped support this research.

Source: Penn State