An autonomous drone called Smellicopter uses a live antenna from a moth to navigate toward smells.

It can also sense and avoid obstacles as it travels through the air.

One huge advantage of drones is that these little robots can go places where people can’t, including areas deemed too dangerous, such as unstable structures after a natural disaster or a region with unexploded devices.

Researchers are interested in developing devices that can navigate these situations by sniffing out chemicals in the air to locate disaster survivors, gas leaks, explosives, and more. But most sensors aren’t sensitive or fast enough to find and process specific smells while flying through the patchy odor plumes these sources create.

“Nature really blows our human-made odor sensors out of the water,” says lead author Melanie Anderson, a doctoral student in mechanical engineering at the University of Washington. “By using an actual moth antenna with Smellicopter, we’re able to get the best of both worlds: the sensitivity of a biological organism on a robotic platform where we can control its motion.”

The moth uses its antennae to sense chemicals in its environment and navigate toward sources of food or potential mates.

“Cells in a moth antenna amplify chemical signals,” says coauthor Thomas Daniel, a professor of biology who co-supervises Anderson’s doctoral research. “The moths do it really efficiently—one scent molecule can trigger lots of cellular responses, and that’s the trick. This process is super efficient, specific, and fast.”

The team used antennae from the Manduca sexta hawkmoth for Smellicopter. Researchers placed moths in the fridge to anesthetize them before removing an antenna. Once separated from the live moth, the antenna stays biologically and chemically active for up to four hours. That time span could be extended, the researchers say, by storing antennae in the fridge.

By adding tiny wires into either end of the antenna, the researchers could connect it to an electrical circuit and measure the average signal from all of the cells in the antenna. The team then compared it to a typical human-made sensor, placing both at one end of a wind tunnel and wafting smells that both sensors would respond to: a floral scent and ethanol, a type of alcohol. The antenna reacted more quickly and took less time to recover between puffs.

Smellicopter homes in on odors

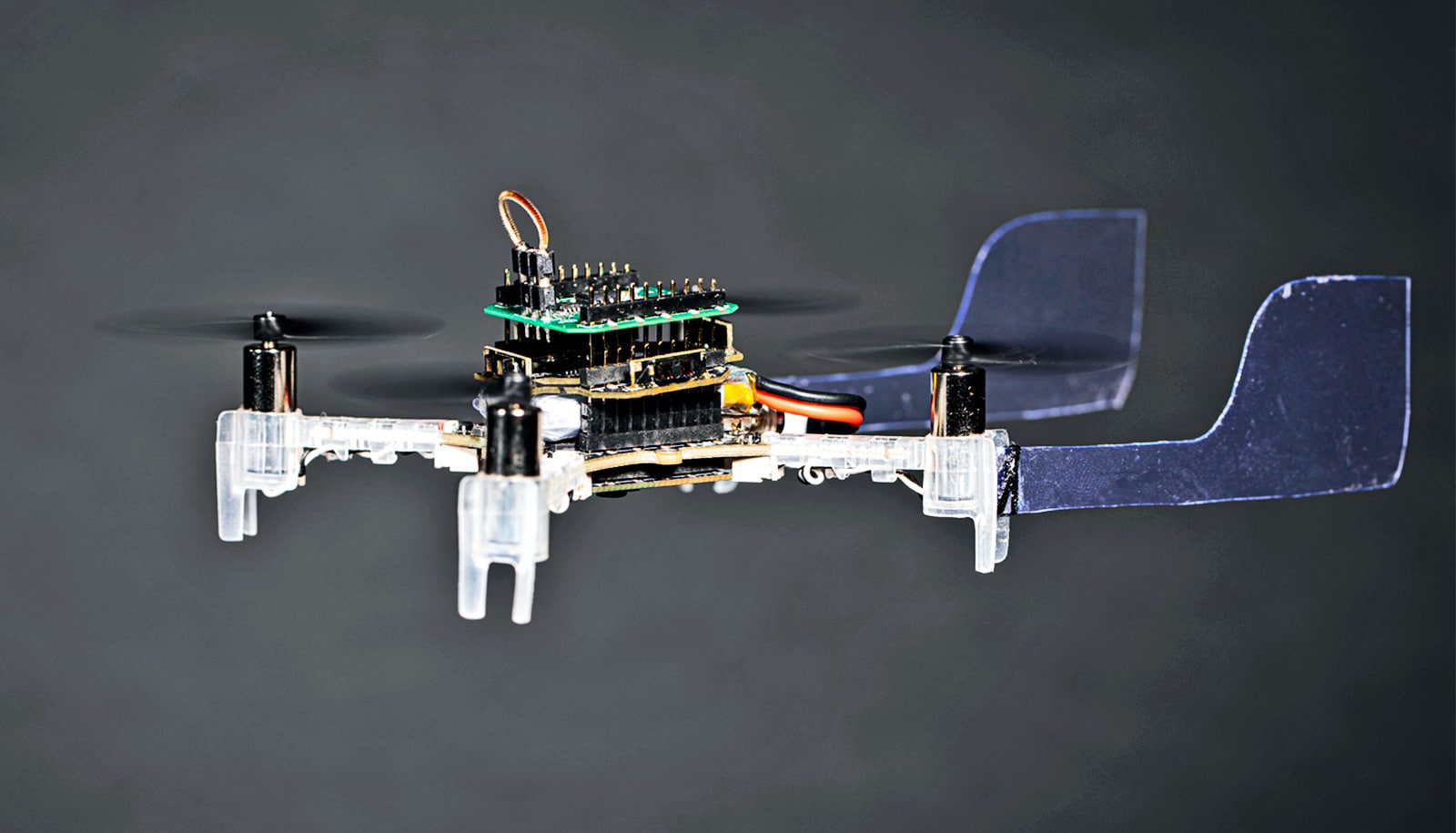

To create Smellicopter, the team added the antenna sensor to an open-source hand-held commercially available quadcopter drone platform that allows users to add special features. The researchers added two plastic fins on the back of the drone to create drag to help it be constantly oriented upwind.

“From a robotics perspective, this is genius,” says coauthor and co-advisor Sawyer Fuller, assistant professor of mechanical engineering. “The classic approach in robotics is to add more sensors, and maybe build a fancy algorithm or use machine learning to estimate wind direction. It turns out, all you need is to add a fin.”

Smellicopter doesn’t need any help from the researchers to search for odors. The team created a “cast and surge” protocol for the drone that mimics how moths search for smells. Smellicopter begins its search by moving to the left for a specific distance. If nothing passes a specific smell threshold, Smellicopter then moves to the right for the same distance. Once it detects an odor, it changes its flying pattern to surge toward it.

Smellicopter can also avoid obstacles with the help of four infrared sensors that let it measure what’s around it 10 times each second. When something comes within about eight inches (20 centimeters) of the drone, it changes direction by going to the next stage of its cast-and-surge protocol.

“So if Smellicopter was casting left and now there’s an obstacle on the left, it’ll switch to casting right,” Anderson says. “And if Smellicopter smells an odor but there’s an obstacle in front of it, it’s going to continue casting left or right until it’s able to surge forward when there’s not an obstacle in its path.”

No GPS needed

Another advantage to Smellicopter is that it doesn’t need GPS, the team says. Instead it uses a camera to survey its surroundings, similar to how insects use their eyes. This makes Smellicopter well-suited for exploring indoor or underground spaces like mines or pipes.

During tests, Smellicopter was naturally tuned to fly toward smells that moths find interesting, such as floral scents. But researchers hope that future work could have the moth antenna sense other smells, such as the exhaling of carbon dioxide from someone trapped under rubble or the chemical signature of an unexploded device.

“Finding plume sources is a perfect task for little robots like the Smellicopter and the Robofly,” Fuller says. “Larger robots are capable of carrying an array of different sensors around and using them to build a map of their world. We can’t really do that at the small scale.

“But to find the source of a plume, all a robot really needs to do is avoid obstacles and stay in the plume while it moves upwind. It doesn’t need a sophisticated sensor suite for that—it just needs to be able to smell well. And that’s what the Smellicopter is really good at.”

Additional coauthors are from the University of Maryland and the University of Washington. The National Defense and Engineering Graduate Fellowship, the Washington Research Foundation, the Joan and Richard Komen Endowed Chair, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research with The Air Force Center of Excellence on Nature-Inspired Flight Technologies and Ideas funded the work.

Source: University of Washington