American judges still cite property cases of enslaved Black people as good law 160 years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

When Justin Simard was conducting research for his dissertation, he came across a case predating the Civil War related to slavery that was cited as precedent in 2012. He started looking for other slavery citations from the past 30 years, thinking he’d find one or two. Instead, he found more than 300.

“What I thought would be a footnote in my dissertation highlighting the odd decisions of a few judges turned into a broader examination of the legal profession’s treatment of slave cases,” says Simard, assistant professor of law at Michigan State University. “Not only are we ratifying their treatment as property in the past but also continuing to treat them as property in the present.”

Simard started the Citing Slavery Project to document the history and continued legacy of the law of slavery in the United States.

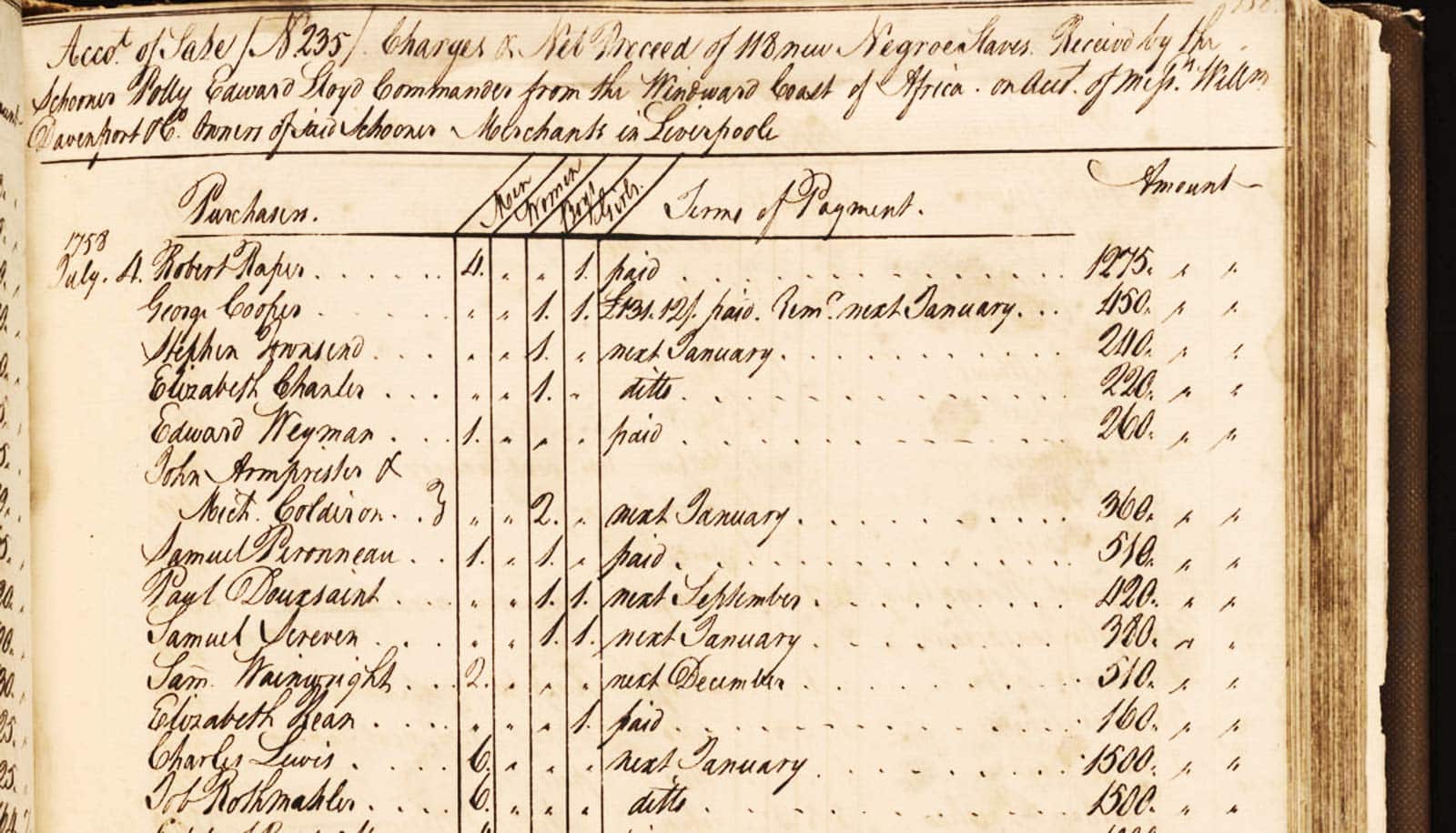

To date, Simard and his team of law students have found more than 7,000 cases involving enslaved people and have created a database of cases from the 20th and 21st centuries that continue to cite them as precedent.

“One of the most surprising things I’ve found is how extensively these cases are cited for so many different reasons,” Simard says. “There’s just so many areas of law—criminal law, property law, criminal procedure—all because in the 19th century, there were so many slave cases. And this is such an important formative era in making American law that just basic ground rules are established in that time. In just about any legal issue you can think of, cases of enslaved people are cited.”

Simard explains that the American legal system is a common law system, meaning that decisions made today are built on decisions of the past. So, when a judge or lawyer has a question, they look back to find comparable questions that have been answered in the past. When they find cases, judges “cite” a case as a way of presenting a similar example.

However, Simard says that in 80% of the cases his team identified, there’s no reference that the citations involve enslaved people.

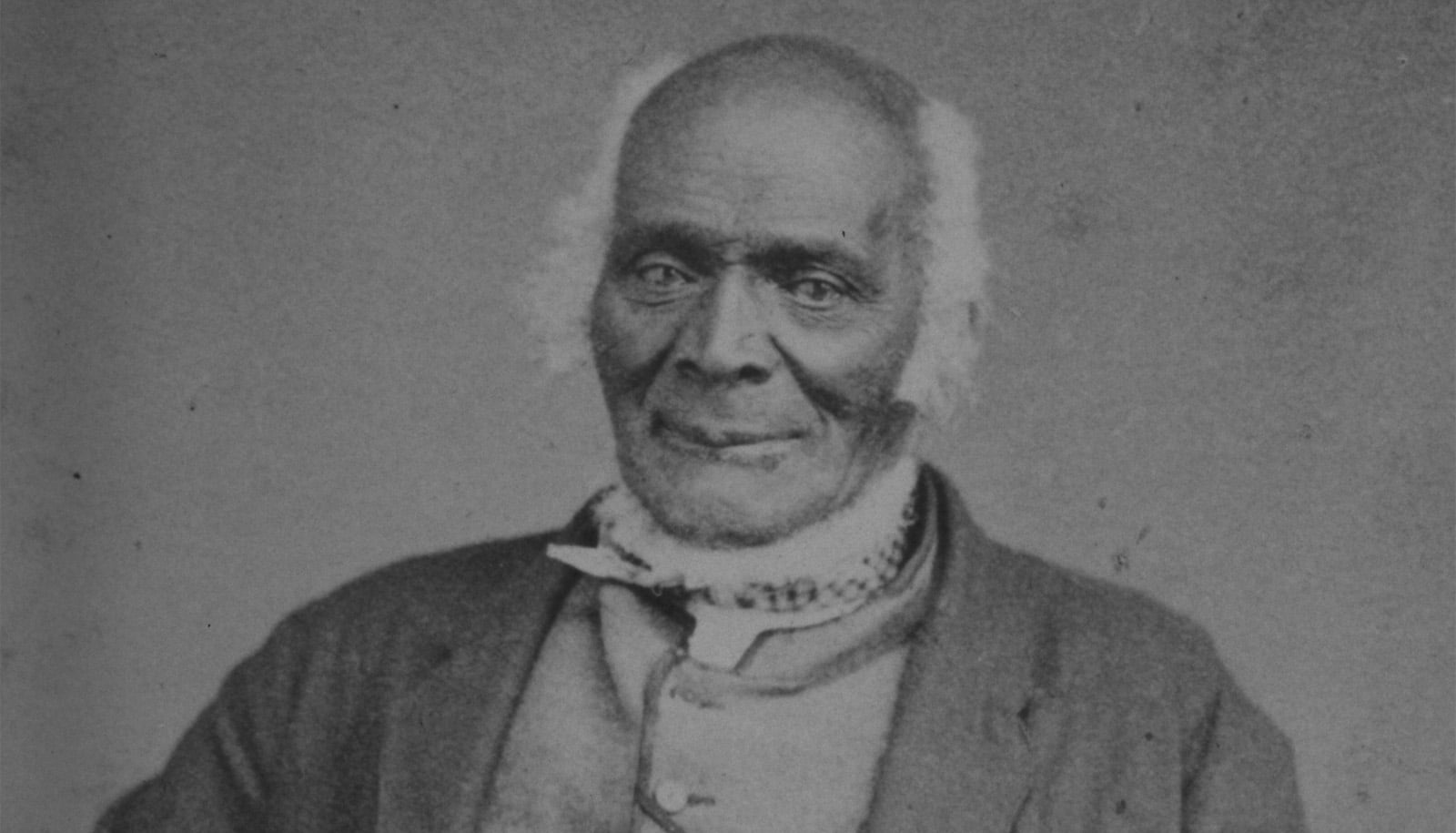

“This was a tragic era in our country’s history, and if lawyers and judges today are continuing to cite slavery cases without acknowledging them as cases concerning enslaved people, they are papering over that era,” Simard says. “It’s a big blind spot. They want to treat these cases as ordinary law.”

Simard says citing slavery cases without acknowledging it “blurs the boundary between people and property.”

For example, a citation about damage to a car or damage to a dump truck that uses precedent about damage to an enslaved person dehumanizes the enslaved person—they’re all basically treated the same.

“Judges today must understand that many judges of the pre-Civil War era were slave owners themselves and made decisions within this context,” Simard says. “And, all of these cases were abrogated, at least in part, by the 13th Amendment, but judges fail to recognize the relevance of emancipation to their decisions.”

Simard and his research team of law students recently found that of all published legal cases throughout American history, 18% are what he calls “two-step” cases—those that cited a case that in turn cited a slavery case to support its argument. And beyond that, he estimates between 30% and 40% of all American legal cases are three-step cases. Simard’s article, “The Precedential Weight of Slavery,” will appear in the journal NYU Review of Law and Social Change.

Compelled to create awareness of enslaved citations, Simard’s team successfully lobbied the editors of “The Bluebook,” the legal profession’s citation bible, to change its rules in its 2021 edition, requiring cases involving enslaved people to be identified with the notation “(enslaved party)” or “(enslaved person at issue).”

“To stop citing these cases without acknowledgement is the first step, but to actually address the underlying issues is a much broader problem,” Simard says.

The legal profession must confront its role in slavery, Simard says.

“American slavery generated thousands of legal disputes,” he says. “Lawyers legitimized slavery by fitting cases involving enslaved people into standard legal categories. Even after emancipation, lawyers continued to treat slave cases as good law. And, today, American judges and lawyers continue to cite slave cases for fundamental legal propositions. It’s likely no coincidence that the legal system continues to create and enforce racial disparities.”

Simard says the law profession loves to pat itself on the back for the role it played in the civil rights movement, but what about the decades before that?

“The pervasive influence of the law of slavery on contemporary American law raises hard questions about what it means to acknowledge and redress the terrible damage that slavery inflicted,” Simard says. “It also raises questions about the law these decisions helped create. Scholars and judges have mostly avoided these questions by treating slave cases, especially those involving routine legal matters, as ordinary law.

“Slave cases are too deeply entwined in American law to completely excise their influence, but ignoring that influence should no longer be an option.”

Source: Michigan State University