Machine learning lets researchers accurately identify signs of Parkinson’s disease by analyzing facial muscles.

Every day, millions of people take selfies with their smartphones or webcams to share online. And they almost invariably smile when they do so.

“What if, with people’s permission, we could analyze those selfies and give them a referral in case they are showing early signs?”

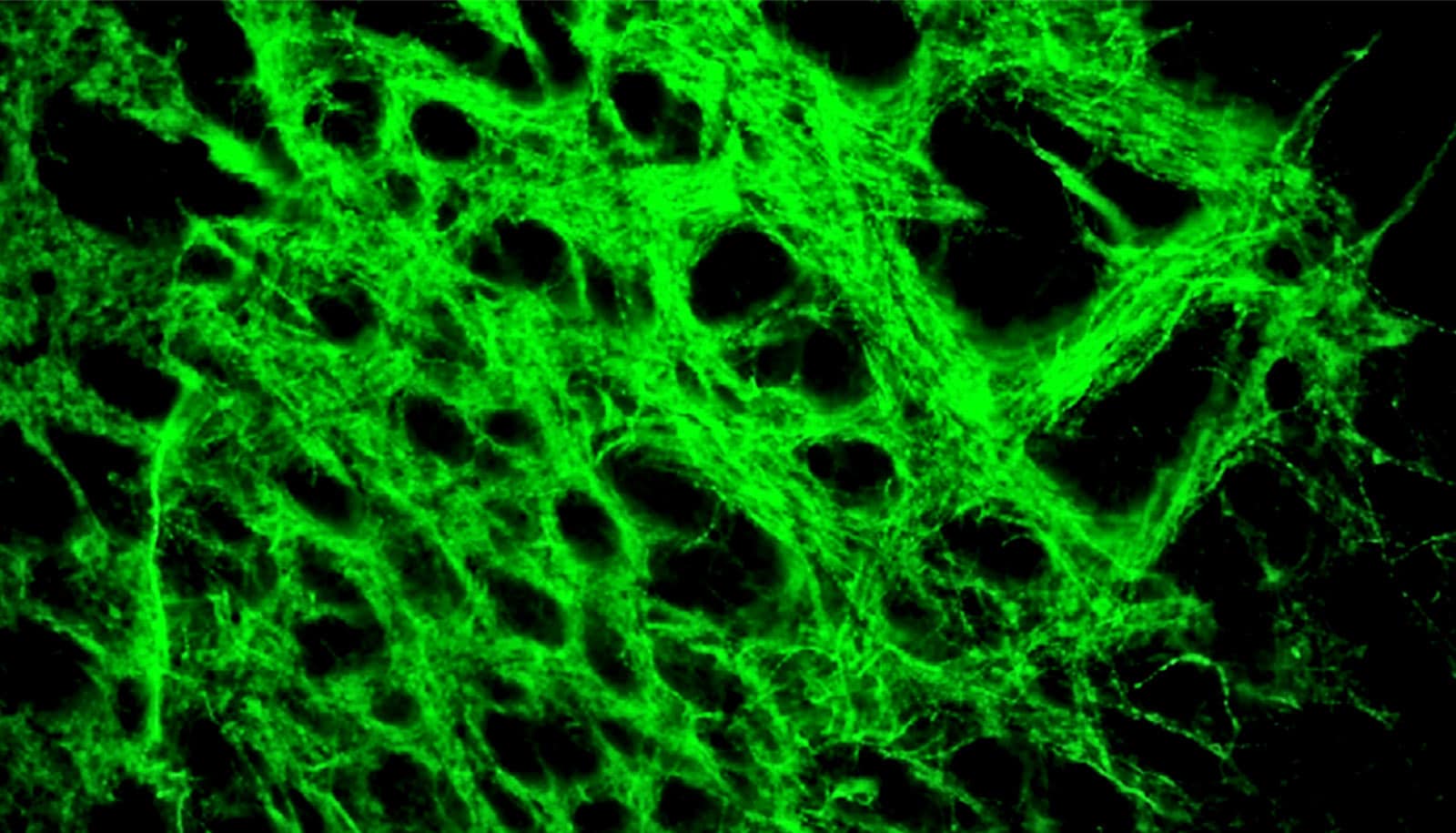

Computer vision software—based on algorithms that the researchers have developed—can analyze the brief videos, including the short clips created while taking selfies, detecting subtle movements of facial muscles that are invisible to the naked eye.

The software can then predict with remarkable accuracy whether a person who takes a selfie is likely to develop Parkinson’s disease—as reliably as expensive, wearable digital biomarkers that monitor motor symptoms.

The researchers’ describe the technology in Nature Digital Medicine.

Checking selfies for Parkinson’s disease risk

“Parkinson’s is the fastest growing neurological disorder,” says Ehsan Hoque, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Rochester. “What if, with people’s permission, we could analyze those selfies and give them a referral in case they are showing early signs?”

Smiles are not the only behaviors that Hoque and his lab can analyze for early symptoms of Parkinson’s disease or related disorders.

The researchers have developed a five-pronged test that neurologists could administer to patients sitting in front of their computer webcams hundreds of miles away.

This could be transformative for patients who are quarantined, immobile, or living in underdeveloped areas where access to a neurologist is limited, Hoque says.

In addition to making the biggest smile, and alternating it with a neutral expression three times, patients taking the test are also asked to:

- Read aloud a complex written sentence

- Touch their index finger to their thumb 10 times as quickly as possible

- Make the most disgusted look possible, alternating with a neutral expression, three times

- Raise their eyebrows as high as possible, then lower them as far as they can, three times slowly

Using machine learning algorithms, the computer program shows—within minutes—a percentage likelihood from each of the tests whether the patient is showing symptoms of Parkinson’s disease or related disorders.

What exactly does the program look for? When patients are making a smile, the software can detect whether they show less control over their facial muscles while doing so, a symptom of Parkinson’s that clinicians refer to as “modularity.”

“One thing about Parkinson’s is that you don’t show all the symptoms all the time, and not every symptom is shown in every part of your body,” says Rafayet Ali, lead author of the paper. “For example, you may not have hand tremors, but you may show a significant level of deviation in your smile.”

Hence the importance of testing other expressions and movements, according to Ali, a former postdoctoral associate in Hoque’s lab who now is an associate data scientist at Sysco.

Updating assessments

Both Hoque and Ali have personal stakes in helping people with Parkinson’s. Their mothers both have had the disorder. Hoque’s late mother in Bangladesh, for example, was put on leovodopa, a leading medication for the disorder, after finally finding one of the country’s few neurologists. The tremors went away. “We were so happy,” Hoque says. Unfortunately, it was difficult to make follow-up appointments, and the tremors eventually returned.

That prompted Hoque to email Ray Dorsey, a professor of neurology, “just to casually chat.” When they finally met in 2016, Hoque recalls, Dorsey “took a big document and just threw it on the table.” The pamphlet contained forms physicians need to fill out as part of the Movement Disorders Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS).

“That’s the gold standard for measuring Parkinson’s,” Dorsey told him. “Everything we do is pen and paper. Any automation, any data analytics that you can bring into this would be a contribution. And he immediately helped us see how we could do that,” Hoque says.

“Objective, digital assessments of Parkinson’s disease can help us diagnose people with the condition and evaluate new therapies for the condition faster,” says Dorsey, an author of Ending Parkinson’s Disease (Public Affairs, 2020).

It will be a while yet, however, before Hoque and his researchers can start seeking permission to analyze people’s selfies, or even before neurologists can deploy the five-pronged test that the researchers have developed.

“An algorithm will never be 100% accurate,” Hoque says. “What if it makes a mistake? We want to be very careful and follow guidance from the FDA if we want anybody from any part of the world to try this and get an assessment.”

Moreover, there is a whole family of movement disorders that are closely related to Parkinson’s disease, including ataxia, Huntington’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and multiple dystrophy.

“They all share similar symptoms of tremor, but the tremors are very different in nature,” Hoque says. “However, even expert neurologists find it very, very difficult to distinguish among them.”

The researchers have made great progress in detecting Parkinson’s disease by automatically analyzing expressions, voice, and motor movements. Yet further work is needed to develop algorithms to differentiate how these involuntary tremors differ across other movement disorders, including ataxia and Huntington’s.

“We can’t tell that just yet,” Hoque says. “But we are in a pursuit of differentiating those tremors using AI to prevent the potential harm of misdiagnosis while maximizing benefit.”

Though ethical and technological considerations still need to be addressed, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation has agreed to fund the research. “The foundation wants us to validate the feedback that we would give people if they did, indeed, show early signs of Parkinson’s—especially if they are performing the test at home,” Hoque says.

“The challenge is not only validating the accuracy of our algorithms but also translating the raw machine-generated output in a language that is humane, assuring, understandable, and empowering to the patients.”

What about speech?

Turns out it’s not just selfies and videos that can help with diagnosing Parkinson’s disease.

More and more, people are using speech-activated smart devices, such as Alexa, Apple Watch, and Google Voice Assistant, to accomplish everyday tasks. Could these devices analyze our speech and voices to alert us if we show early warning signs of Parkinson’s disease?

Recent work by Rochester researchers suggests it’s entirely possible. Wasifur Rahman, Sangwu Lee, Md. Saiful Islam, and other students in Hoque’s lab published findings in the Journal of Medical Internet Research that show how an online tool can be used to help screen almost anyone anywhere for Parkinson’s disease remotely using video- or audio-enabled speech tasks.

Taken together, the researchers’ efforts are contributing to a future in which equity and access to neurological care is as ubiquitous as owning a smart phone or other internet-enabled device.

Source: University of Rochester