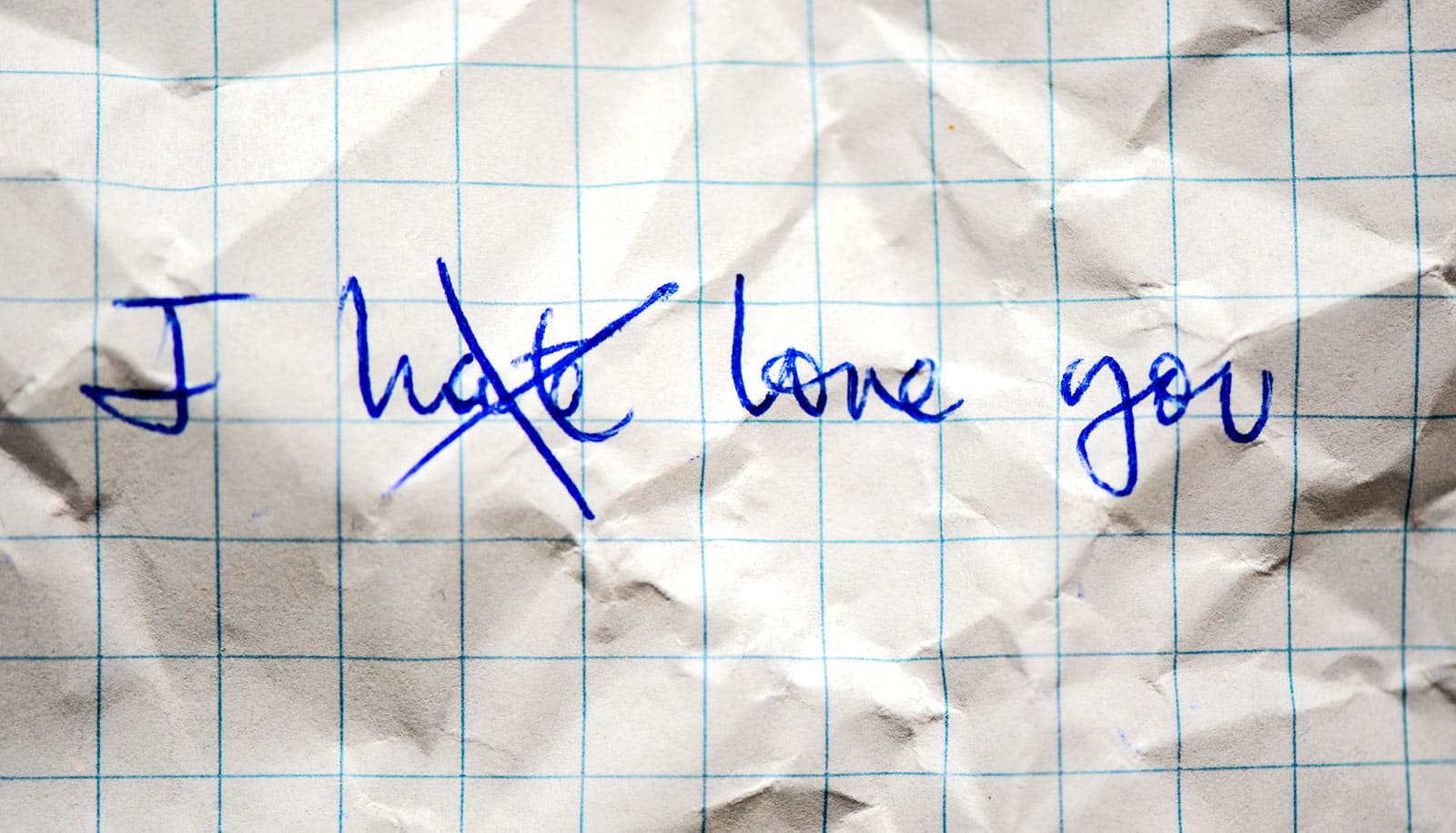

Over time, being in an on-again-off-again relationship can have a lasting negative influence on mental health, research shows.

The negative effects sometimes linger on for more than a year, says researcher Kale Monk, assistant professor at the University of Missouri.

“We’re seeing several consequences associated with remaining in these relationships, such as less relationship satisfaction, poorer communication, less commitment, more intimate partner violence, and in this particular study, finding that it’s associated with depression and anxiety symptoms over time,” Monk says.

Monk and his colleagues surveyed 545 individuals who were in relationships. Approximately 34% of partners reported relationship cycling, which means they had experienced at least one cycle of breakup and reconciliation in their relationship. He used established measures of depression and anxiety symptoms to analyze the mental health of the individuals in the relationship.

Relationship cycling

In an earlier study, Monk found that on-again, off-again relationship cycling was associated with psychological distress and that those who cycled more frequently—in and out of the same relationship—also reported more distress symptoms. However, in this most recent study, he found that these same debilitating effects can last much longer.

“We followed these people over time, and we found that our prior findings ring true over a year out,” Monk says. “Breaking up and getting back together previously in your relationship was associated with more symptoms of psychological distress over a 15-month period.”

While it can be distressing to be in an on-again, off-again relationship, getting out of one could have well-being benefits. In fact, in a related study, Monk surveyed divorcing individuals—in other words, people who were in the “off” phase of their relationships—and found that, for women who had experienced cycling in their prior relationship, they reported fewer distress symptoms than those who did not experience cycling previously. Monk and his team speculate that these women might have experienced a sense of relief derived from exiting the unstable relationship.

Return to a past love?

Monk says these findings put popular media portrayals of relationship cycling in context. As romantic comedies became increasingly popular, so did the trend of narratives display these relationships in an idealized way.

“There can be a lot of popular narratives that make us think that returning to a former partner is a good idea,” Monk says. “We see it quite often in movies and TV shows, where the main characters break up and get back together. It can lead us to believe that it’s an ideal situation that people should want.”

Although this trend may be problematic for many, returning to a relationship that previously ended is not always doomed to fail.

“In some of our other studies, we certainly do hear from partners who report that time apart made them realize how much they valued each other and they were rededicated to making it work,” Monk says.

Monk adds that it depends on the situation and whether or not cycling becomes a repeated pattern.

“If somebody is considering getting back together with a former partner, it’s really important to consider what caused the breakup and work to make improvements so the pattern does not continue,” Monk says. “It’s also important for the couple to have conversations about what is going to change. How is this relationship going to be different moving forward?”

The latest findings appear in Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Sciences.

Source: University of Missouri