The federal response to hurricanes Harvey and Irma was faster and more generous than the help sent to Puerto Rico in preparation for and in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, a new study shows.

For example, within nine days of the landfall of both Harvey and Irma, survivors had received nearly $100 million in FEMA dollars, while María survivors had received just slightly over $6 million.

“What we found is that there was a very significant difference in not only the timing of the responses but also in the volume of resources distributed in terms of money and staffing,” says lead author Charley Willison, a doctoral candidate in the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health.

“Overall, Hurricane Maria had a delayed and lower response across those measures compared to hurricanes Harvey and Irma. It raises concern for growth in health disparities as well as potential increases in adverse health outcomes.”

Staffing efforts also fell short, the report notes. At its peak, federal personnel on-site for Hurricane Harvey in Texas reached 31,000 people and 40,000 responded to Irma in Florida during the first 180 days post-hurricane. By comparison, at its peak during the same period, there were 19,000 federal personnel on-site helping with Hurricane Maria recovery.

Further, it took four months for disaster appropriation funding to Puerto Rico to reach the same levels that Texas and Florida received in two months.

“The analysis shows that the disaster response to the three hurricanes did not align with storm severity and may affect deaths and recovery rates,” Willison says.

The findings are important because “not only was the lack of emergency response a likely contributor to thousands of avoidable deaths, it was also a reminder of the penalties of not being fully represented in federal politics,” says Scott Greer, professor of health management and policy and of global public health. “Democracy is a public health policy.”

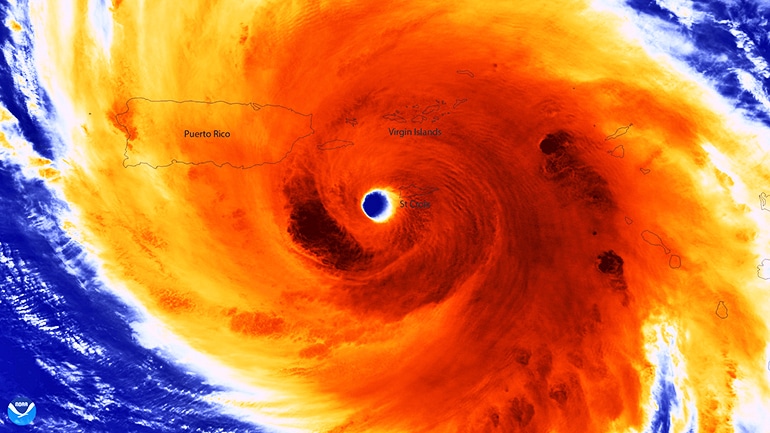

For the study, which appears in BMJ Global Health, researchers used publicly available data from the Federal Emergency Management Authority, National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, the Puerto Rican government, and George Washington University.

Additional authors are from the University of Michigan and the University of Utah.

Source: University of Michigan