The genetic basis of air-breathing and limb movement was established in our fish ancestor 50 million years before vertebrates transitioned from water to land, report researchers.

There is nothing new about humans and all other vertebrates having evolved from fish. The conventional understanding has been that certain fish shimmied landwards roughly 370 million years ago as primitive, lizard-like animals known as tetrapods. According to this understanding, our fish ancestors came out from water to land by converting their fins to limbs and breathing under water to air-breathing.

However, limbs and lungs are not innovations that appeared as recent as once believed. Our common fish ancestor that lived 50 million years before the tetrapod first came ashore already carried the genetic codes for limb-like forms and air breathing needed for landing. These genetic codes are still present in humans and a group of primitive fishes, according to the new research.

“The water-to-land transition is a major milestone in our evolutionary history. The key to understanding how this transition happened is to reveal when and how the lungs and limbs evolved. We are now able to demonstrate that biological functions occurred much earlier before the first animals came ashore,” says professor Guojie Zhang from the Villum Centre for Biodiversity Genomics at the University of Copenhagen’s biology department, who is the lead author of the study in Cell.

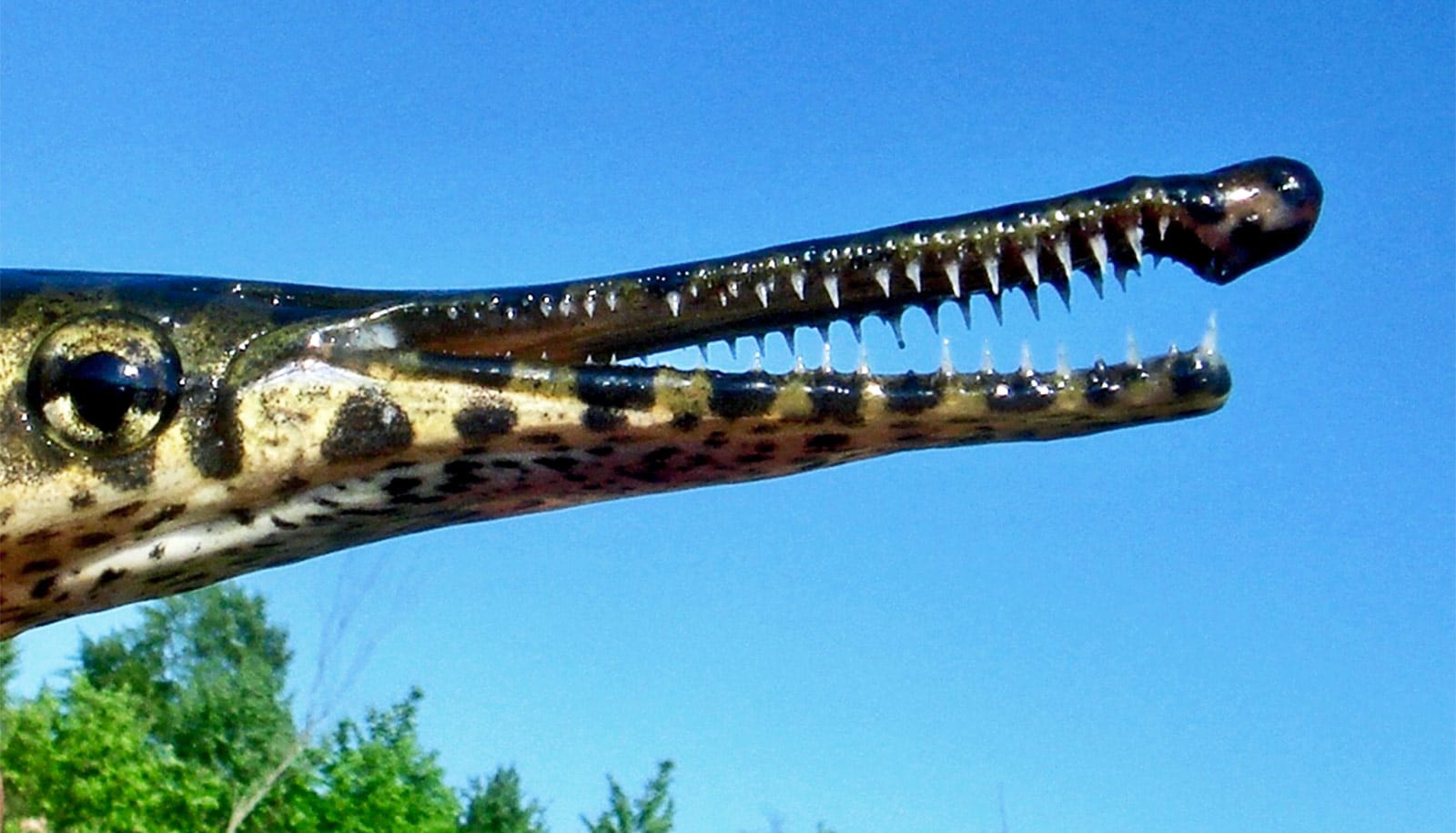

Using pectoral fins with a locomotor function like limbs, the bichir can move about on land in a similar way to the tetrapod. Researchers have for some years believed that pectoral fins in bichir represent the fins that our early fish ancestors had.

The new genome mapping shows that the joint which connects the so-called metapterygium bone with the radial bones in the pectoral fin in the bichir is homologous to the synovial joints in humans—the joints that connect upper arm and forearm bones. The DNA sequence that controls the formation of our synovial joints already existed in the common ancestors of bonefish and is still present in these primitive fishes and in terrestrial vertebrates. At some point, this DNA sequence and the synovial joint was lost in all of the common bony fishes—the teleosts.

“This genetic code and the joint allows our bones move freely, which explains why the bichir can move around on land,” says Zhang.

Moreover, the bichir and a few other primitive fishes have a pair of lungs that anatomically resembles ours. The new study in reveals that the lungs in both bichir and alligator gar also function in a similar manner and express same set of genes as human lungs.

The study also demonstrates that the tissue of the lung and swim bladder of most extant fishes are very similar in gene expression, confirming they are homologous organs as Charles Darwin predicted. But while Darwin suggested that swim bladders converted to lungs, the study suggests it is more likely that swim bladders evolved from lungs.

The research suggests that our early bony fish ancestors had primitive functional lungs. Through evolution, one branch of fish preserved the lung functions that are more adapted to air breathing and ultimately led to the evolution of tetrapods. The other branch of fishes modified the lung structure and evolved with swim bladders, leading the evolution of teleosts. The swim bladders allow these fishes to maintain buoyancy and perceive pressure, thus better survive under water.

“The study enlightens us with regards to where our body organs came from and how their functions are decoded in the genome,” explains Zhang. “Thus, some of the functions related to lung and limbs did not evolve at the time when the water-to-land transition occurred but are encoded by some ancient gene regulatory mechanisms that were already present in our fish ancestor far before landing. It is interesting that these genetic codes are still present in these ‘living-fossil’ fishes, which offer us the opportunity to trace back the root of these genes.”

The Villum Foundation, among others, supported the research.

Source: University of Copenhagen