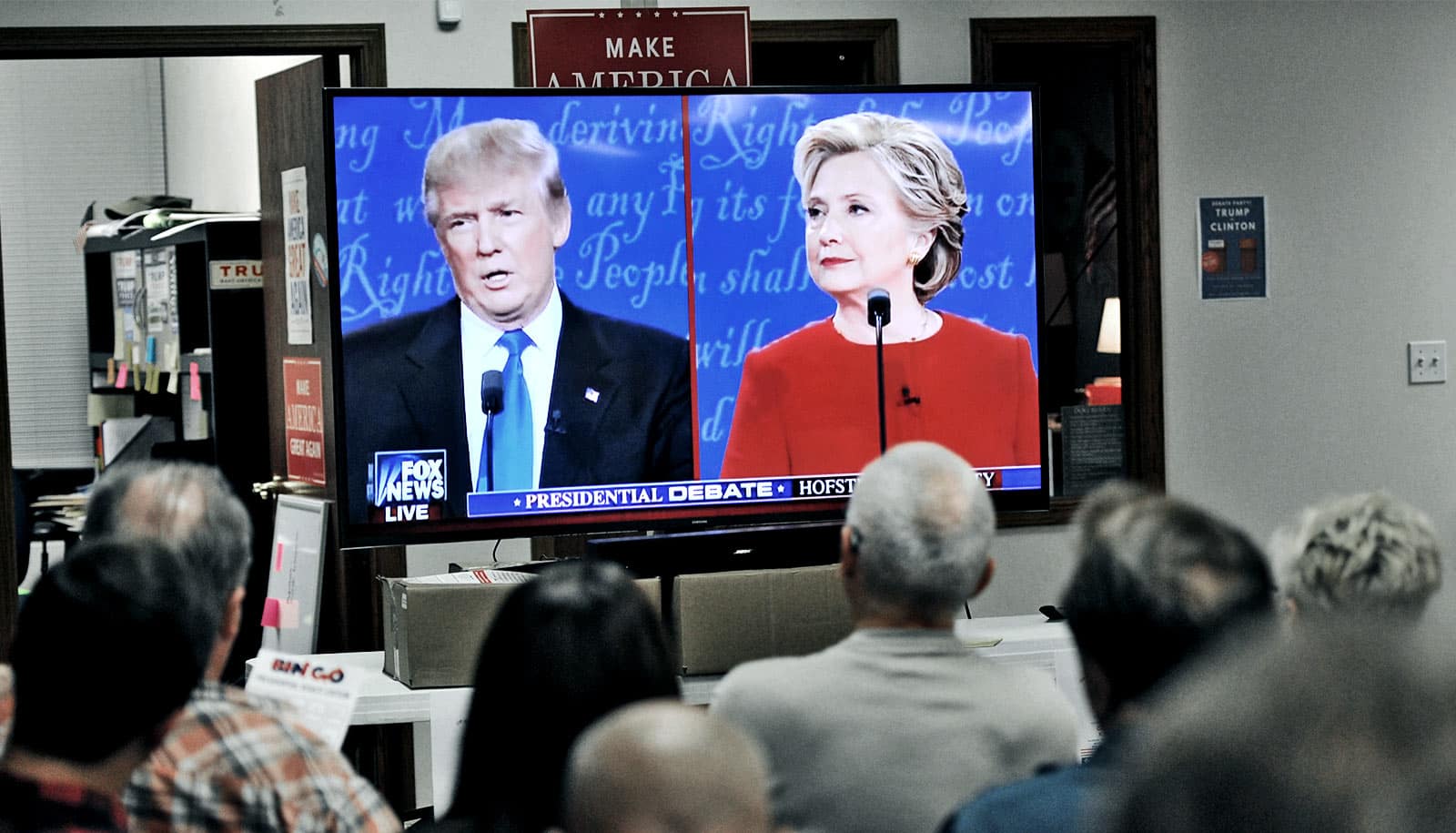

Men and woman had significantly different emotional responses to the first presidential election debate in 2016 between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, according to research using facial-recognition software.

Unlike traditional political science debate assessment that relies on post-debate interviews or real-time self-reporting, the researchers recorded viewers with webcams as they watched the debate on desktop computers. They then used facial-recognition software for a frame-by-frame analysis of emotional expression.

The technology features a facial expression coding system that tracked 20 unique movements such as furrowing the brow, wrinkling the nose, or frowning—markers of particular emotions like surprise, sadness, anger or disgust, says Sarah Allen Gershon, an associate professor of political science at Georgia State University, and corresponding author of the paper.

The impact of emotions was stronger for women viewers and gender issues were more important for them as well, the researchers found.

“Women expressed internalizing emotions like sadness twice as often as men,” says Gershon.

“…women’s expressions of sadness and men’s expressions of anger increased during periods when Clinton spoke more.”

“Men expressed externalizing emotions like anger and disgust more often. There were also differences in when men and women expressed these emotions. Our data indicated that women’s expressions of sadness and men’s expressions of anger increased during periods when Clinton spoke more.”

Gershon stresses that gender was uniquely at the fore of the event, which had the largest audience of any US presidential debate in history with 84 million viewers. Clinton was the first woman to be nominated for President of the United States by a major political party.

There had also been prominent discussions of gender during the campaign, including Trump’s high-profile comments about women’s appearances, and Clinton highlighting her glass-ceiling-breaking nomination.

“We found that the impact of emotional expressions was more powerful for women than men in predicting post-debate evaluations of the candidates’ debate performance, particularly in their evaluations of Trump’s performance,” Gershon says.

“For example, as women showed more expressions of fear, their ratings of Trump’s performance decreased significantly. However, as men expressed more fear, their evaluations of the candidates’ performance barely budged.”

Though marketing research has used facial recognition software for years, Gershon says it is a relatively new tool for political scientists. “Now that we have the software, it would be interesting to look at how people are looking at different types of stimuli like speeches or ads or website messaging,” she says.

“The broad question that we are concerned with for this study is, do debates matter? Are they educators for the population? The answer from our paper is that debates do matter in distinct and different ways for people watching them.”

The research appears in the journal Political Behavior. Additional coauthors are from Georgia State and Arizona State universities.

Source: Georgia State University