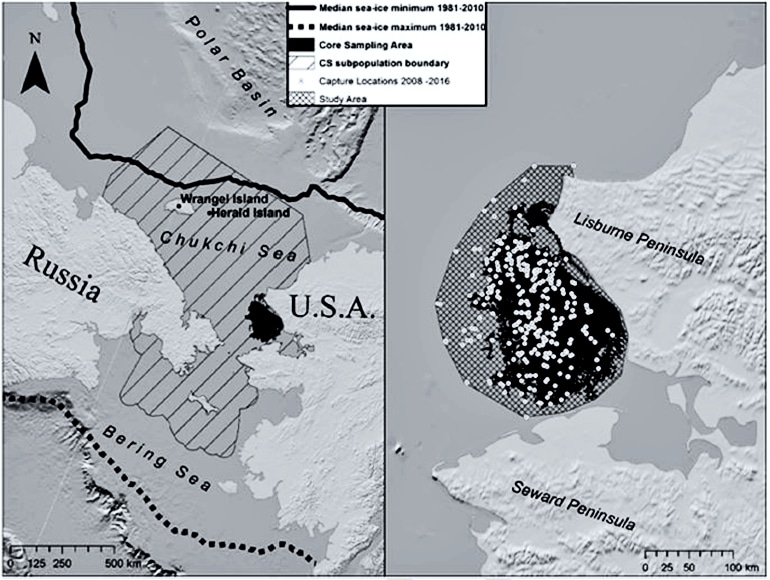

Not all polar bears are in the same dire situation as they face retreating sea ice, at least not right now, a new study shows. Those that hang out in the Chukchi Sea off the western coast of Alaska are doing well. But they’ve never been counted. Until now.

The first formal study of this population, which appears in Scientific Reports, suggests it’s been healthy and relatively abundant in recent years, numbering about 3,000 animals.

“This work represents a decade of research that gives us a first estimate of the abundance and status of the Chukchi Sea subpopulation,” says first author Eric Regehr, a researcher with the Polar Science Center at the University of Washington.

“Despite having about one month less time on preferred sea ice habitats to hunt compared with 25 years ago, we found that the Chukchi Sea subpopulation was doing well from 2008 to 2016,” Regehr says.

“Sea-ice loss due to climate change remains the primary threat to the species but, as this study shows, there is variation in when and where the effects of sea-ice loss appear. Some subpopulations are already declining while others are still doing OK.”

Stressed bears

Of the world’s 19 subpopulations of polar bears, the US shares two with neighboring countries. The other US subpopulation—the southern Beaufort Sea polar bears, whose territory overlaps with Canada—is showing signs of stress.

“The southern Beaufort Sea subpopulation is well-studied, and a growing body of evidence suggests it’s doing poorly due to sea-ice loss,” Regehr says.

The US Endangered Species Act in 2008 listed polar bears as threatened due to declining sea ice, which the animals depend on for hunting, breeding, and traveling. But the new study suggests that such effects are not yet visible for bears in the remote waters that separate Alaska from Chukotka, Russia.

“It’s a very rich area. Most of the Chukchi Sea is shallow, with nutrient-rich waters coming up from the Pacific. This translates into high biological productivity and, importantly for the polar bears, a lot of seals,” Regehr says.

Previous studies by the State of Alaska show that ringed and bearded seals have maintained good nutritional condition and reproduction in the Chukchi Sea region, Regehr says.

“Just flying around, it’s night and day in terms of how many seals and other animals you see. The Chukchi Sea is super productive and the Beaufort Sea is less so,” he says.

The area also has an abundance of whale traffic, and when carcasses wash up on shore the polar bears can feed on them in summer, when the sea ice melts and a portion of the Chukchi Sea subpopulation waits on land for the ocean to refreeze.

Recent ecological observations had suggested that Chukchi Sea bears are doing well. A study led by coauthor Karyn Rode, at the US Geological Survey, showed the top predators have similar amounts of body fat as 25 years ago, a good indicator of their overall health.

GPS tracking

The study is the first assessment of the subpopulation size using modern methods. It estimates just under 3,000 animals, with generally good reproductive rates and cub survival.

As a federal wildlife biologist based in Alaska until 2017, Regehr and colleagues gathered the data by tagging roughly 60 polar bears in most years from 2008 to 2016. He flew by helicopter over the area just north of Alaska’s Seward Peninsula, looking for tracks on the sea ice.

The helicopter then would follow tracks in the snow to locate the bear and use a tranquilizer dart to sedate the animal. Over about an hour, researchers would weigh the bear, collect biological samples, apply individual tags and, in some cases, attach a GPS transmitter.

All the data were incorporated into a new model designed to estimate population size for large carnivores that are highly mobile and whose territory spans a large region. The authors made the model publicly available in the hope that it will be used on other populations or species.

“Polar bears can travel thousands of miles in a year. But with the GPS tags, we can see when a bear leaves our study area but is still alive, because it’s moving. This information is key because there are bears that we see once and never see again, and to get a good population estimate you need to know if these animals died or just moved to a new area,” Regehr says.

Native hunters

For the first time, the model also considered local and traditional ecological knowledge that the North Slope Borough of Alaska collected from Native hunters and community members who have generations of experience with polar bears.

“It was important to bring our science together with the observations and expertise of people who live in polar bear country year-round and understand the animals in different ways,” Regehr says.

A joint US-Russia commission is responsible for management and conservation of the Chukchi Sea subpopulation. In response to the new assessment, the commission raised the sustainable level of subsistence harvest, which is nutritionally and culturally important to Native people in Alaska and Chukotka.

“These polar bears move back and forth between the US and Russia, so it’s very much a shared resource,” says Regehr.

“These findings are good news for now, but it doesn’t mean that bears in the Chukchi Sea won’t be affected by ice loss eventually,” Regehr says. “Polar bears need ice to hunt seals, and the ice is projected to decline until the underlying problem of climate change is addressed.”

Additional coauthors are from the University of Washington, the US Geological Survey, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service in Alaska.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service, the US Geological Survey, the University of Washington, the US Air Force, the State of Alaska, the Bureau of Ocean and Energy Management, the Bureau of Land Management, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation funded the work.

Source: University of Washington