Thanks to a new 3D cell culture technique, it may be possible to personalize treatment by understanding the contributions of different cell types in a tumor to the cancer’s behavior.

Each cancer patient’s tumors have cells that look and act differently, making it difficult for scientists to determine treatments based on tumors grown from generic cell cultures in the lab.

“Creating specific treatments that can address an individual patient’s cancer is the Holy Grail of personalized therapy, and now we’re one step closer.”

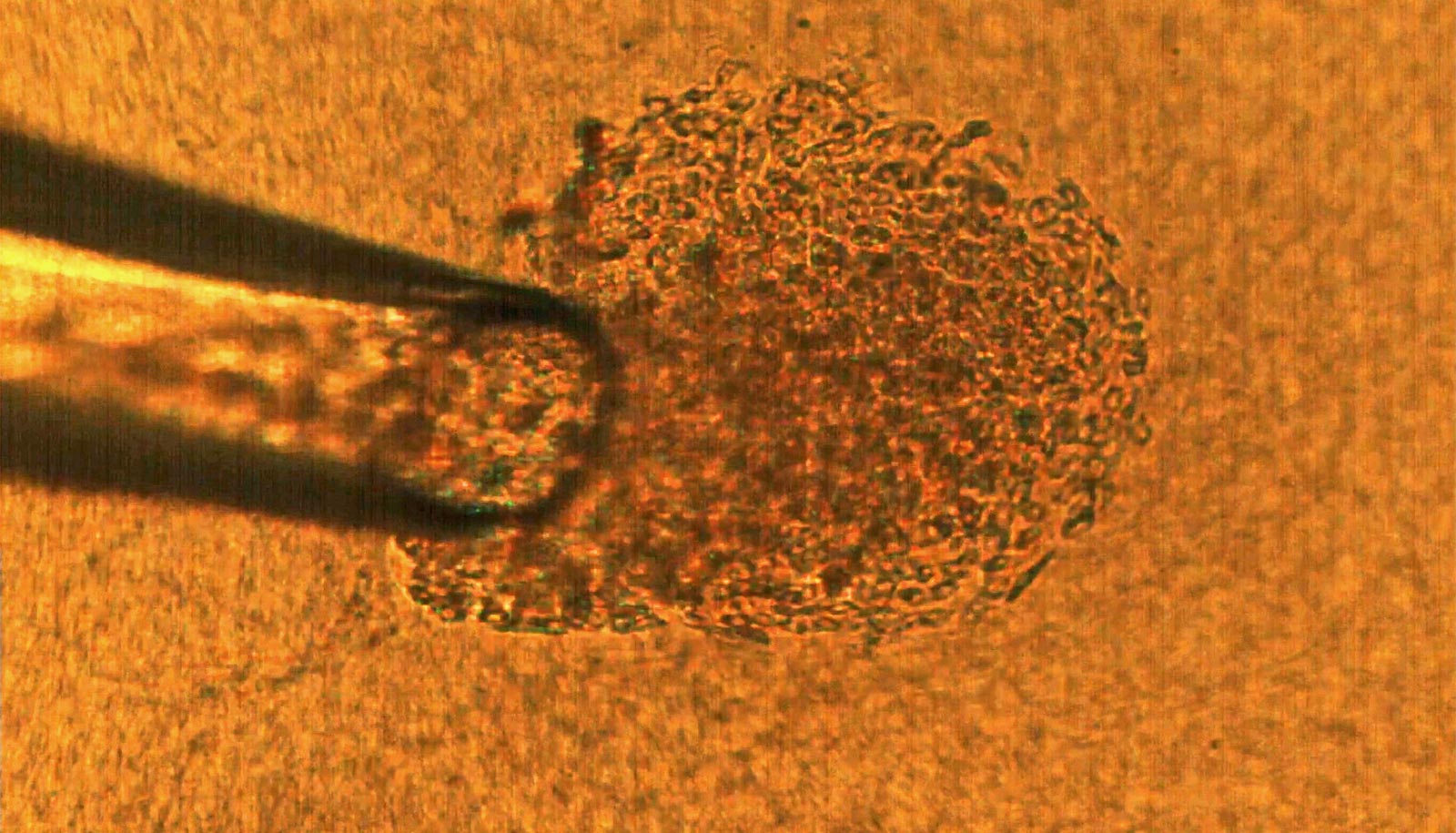

The new technique recreates tumors in the lab from single cells.

“I see a future where a cancer patient gives a blood sample, we retrieve individual tumor cells from that blood sample, and from those cells create tumors in the lab and test drugs on them,” says Cagri Savran, professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University. “These cells are particularly dangerous since they were able to leave the tumor site and resist the immune system.”

Cell culture is a technique that biologists use to conduct research on normal tissue growth as well as on specific diseases. A 3D cell culture permits the formation of tumors from cancer cells that grow in three dimensions, meaning that the tumor is more like a three-dimensional potato than a two-dimensional leaf.

Cancer cell heterogeneity

The team is the first to demonstrate a 3D cell culture from individually selected cells. This feat, described in a paper in Scientific Reports, will allow scientists to more accurately know the impact of each cell on a tumor’s formation and behavior.

“To produce tissue samples that are close to what we have in the body, which allows us to do high-fidelity research in the laboratory, we need to place cells in an environment that mimics their natural milieu, allowing the cells to organize into recognizable structures like tissues in vivo,” says Sophie Lelièvre, a professor of cancer pharmacology in the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Current 3D cell culture techniques have their limits, says Lelièvre, who studies 3D cell culture and helps design new cell culture methods as scientific director of the 3D Cell Culture Core (3D3C) Facility at the Birck Nanotechnology Center of Purdue’s Discovery Park.

Real tumors, for example, are made up of cells of various phenotypes, or behaviors. How different these cells are from each other is described by the term “heterogeneity.” Researchers say they don’t yet fully understand the cellular heterogeneity of real tumors.

“Within a tumor, most cells are cancerous, but they do not have the same phenotype,” Lelièvre says. “It has been proposed that some tumors respond to chemotherapy, and some are resistant depending on the degree of heterogeneity of these phenotypes. It’s difficult to pinpoint treatments based on tumors grown in the lab because every patient’s tumors have different levels of heterogeneity.”

Individual tumor cells

A typical cell culture dish or device also has a large number of cells. Scientists have no control over which cells develop into tumors. To understand how the heterogeneity inside a tumor develops and drives resistance to treatment, scientists need to study the contribution of each cell phenotype to the tumor by selecting individual cells and studying their impact.

Savran had previously demonstrated a microfluidic device capable of isolating single cancer cells from a blood sample.

“These cells are extremely rare,” Savran says. “With a sample with billions of cells, we may find just one or two tumor cells. But since we’ve figured out how to find them, we can now hand them off to people like Sophie to help study their heterogeneity.”

Savran’s team created a mechanical device that successfully extracted single tumor cells from existing cell lines of breast and colon cancers. They deposited each single cell onto a matrix gel island following Lelièvre’s advice.

After several days, the team observed that many of the selected single cells had developed into tumors that displayed degrees of aggressiveness corresponding to the cancer subtype of origin. The cells also recreated phenotypic heterogeneity, as shown with an imaging-based quantitative approach used previously by the Lelièvre lab.

“What Cagri’s technique did is really priceless,” Lelièvre says. “By simply analyzing the morphology of the tumors developed from individual cells, we could confirm that the degree of heterogeneity among tumors of the same cancer subtype increases with time without any other pressure or stimuli than those exerted by the growth of the tumor itself.”

The researchers also demonstrated that the degree of phenotypic heterogeneity inside a tumor depends on the cell of origin and could be related to fast-growing tumors for a specific breast cancer subtype, bringing new directions of research to understand the underlying mechanisms of aggressiveness in cancers.

“Creating specific treatments that can address an individual patient’s cancer is the Holy Grail of personalized therapy, and now we’re one step closer,” Savran says.

Source: Purdue University

“I see a future where a cancer patient gives a blood sample, we retrieve individual tumor cells from that blood sample, and from those cells create tumors in the lab and test drugs on them,” says Cagri Savran. (Credit: