The new coronavirus variant—first detected in South Africa, and named Omicron by the World Health Organization—has stirred up concerns around the world.

It’s sent stock markets on a roller-coaster ride, triggered new air travel bans, and raised a number of questions.

President Joe Biden addressed the American public after Thanksgiving, calling for calm and stating the variant should be a “cause for concern, not a cause for panic.”

“We have more tools today to fight the variant than we’ve ever had before,” he said at a White House press conference. “You have to get your vaccine—you have to get the shot, you have to get the booster.”

Scientists are scrambling to understand how the mutations in Omicron may affect the virus’ transmissibility and mortality rate and whether or not existing COVID-19 vaccines are effective against it.

Infectious disease expert Davidson Hamer is a member of Boston University’s Medical Advisory Group, which has been guiding the university’s COVID-19 response since March 2020. He also chairs a group where clinicians and leaders from Boston University, Harvard University, Tufts University, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology share data and insights on campus coronavirus response efforts.

Here, Hamer talks about what’s different about the Omicron variant, how, or even if, we should change our behavior, and if all the news coverage is just a lot of hype:

It seems like a lot of media coverage is focusing on the potential scary outcomes of Omicron—does it seem too early for that message to be sent? What’s your temperature read on how balanced the reporting has been on this?

I think there’s been a lot of overreaction—[including] governments banning air travel. The [public health] measures that have been in place, if continued to be effectively utilized—such as [preflight] COVID testing, ensuring travelers are vaccinated, doing predeparture testing within 48 to 72 hours of traveling, or quarantining upon arrival, with COVID testing five to seven days later—those kinds of measures should help limit the spread of new variants broadly, meaning all new coronavirus variants, including Omicron.

There’s been a little too much hype, saying this is the next scary thing, but we don’t know much about it yet.

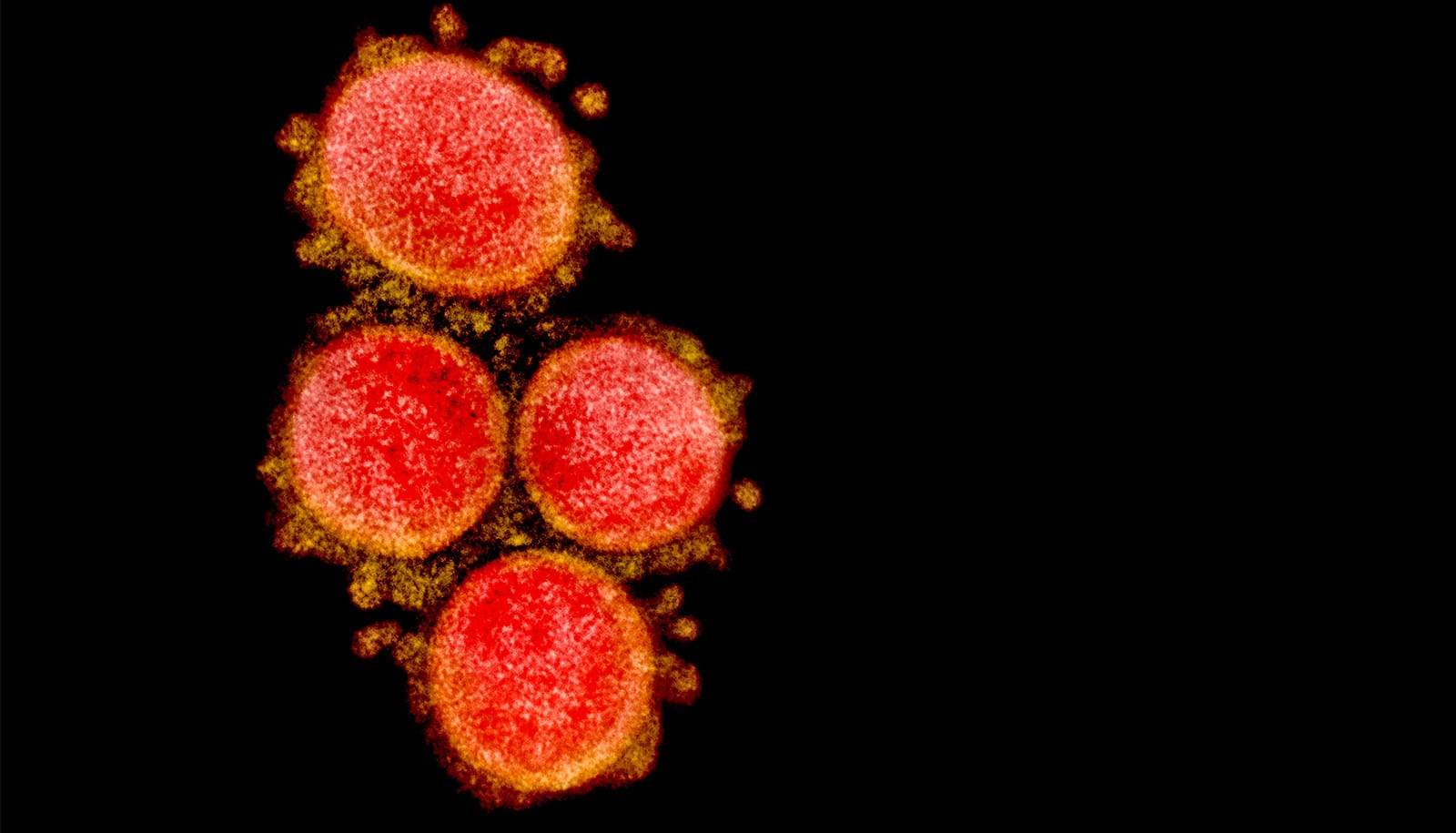

Many reports are saying that Omicron has significantly more variations to the virus’ spike protein than other variants. Is that the case or are these levels of mutations par for the course in terms of how viruses mutate?

I think it’s par for the course, but the concern is that the number of mutations is much higher than we’ve seen in previous variants. It’s a much larger number of mutations in areas of the virus that are important for binding to cells, and if the virus is better able to bind to cells, that means it could lead to a higher concentration of virus and be more transmissible.

Is this going to be much more transmissible? Is this a greater threat [than previous variants]? We don’t know yet. The reassuring thing is that the measures we’ve been using to control the spread of COVID-19—avoiding public gatherings, mask use, ventilation, anybody who has symptoms getting tested and isolated, close contacts going into quarantine—all those public health measures will work to control the spread of this variant, too.

Is the arrival of Omicron on the global scene a reason for people here to start changing their behavior now?

I don’t think Omicron is a reason to change behavior now, but the case numbers for the state have been rising gradually, and if you look at some of the surrounding states, they’re seeing a progressive rise, too.

Maine and Vermont are starting to have a bit of a health care [capacity] impact. In Massachusetts, we’ve had a slight increase in terms of hospitalization, but it’s been nowhere [close to] where we were in terms of April 2020, and that’s thanks to the protective effect of vaccines.

[…] With good public health mitigation efforts, we should be able to reduce spread and reduce risk. I would be cautious eating out at restaurants and being inside public places where mask use cannot be maintained.

For gathering with family and friends, make sure everyone is vaccinated, and think about ways to create better ventilation, maybe opening a window. I’d back off a little on eating out and being in public venues where not everyone is wearing masks and where ventilation may not be sufficient.

What’s the biggest takeaway people should have from the Omicron news?

I think the biggest thing is, we have very little information so far. The variant is characterized genetically, but clinically and from a public health standpoint, we know little. Is it more transmissible? Does it evade the immune response from vaccination? I think right now, the answer to most questions is, we need more evidence.

We need to reassure people—there is a global panic setting in, and it’s overdone. If we stick with the tried-and-true infection control measures—I don’t think we need to do a complete lockdown—and we are more cautious during the next four to eight weeks going through the holidays, all that will help keep things under reasonable control.

Is there any hope that Omicron won’t turn out to be as bad as people fear it will be?

The Mu variant, which was circulating in Colombia and Ecuador, just sort of fizzled out. That’s an example of a variant of concern that didn’t end up panning out to be a major threat.

The Omicron mutations seem to be in places of the virus that would increase transmissibility. How does increased transmissibility of a virus affect its mortality rate?

If a virus is better able to transmit and propagate, but it kills its host quickly, it will stop spreading. So, there is roughly an inverse relationship—if it’s much more transmissible, it’s usually associated with less mortality, and lower risk of death.

But it’s hard to say whether that’s the case for Delta, for example. Delta is much more transmissible [than earlier coronavirus variants], but in many places where Delta has circulated, there has been an increasing number of people getting vaccinated. Generally speaking, if a virus becomes more able to kill its host quickly, it is not able to spread very far. High mortality is not technically good for a virus that wants to spread.

Hamer is also faculty member of the School of Public Health, School of Medicine, and National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories as well.

Source: Boston University