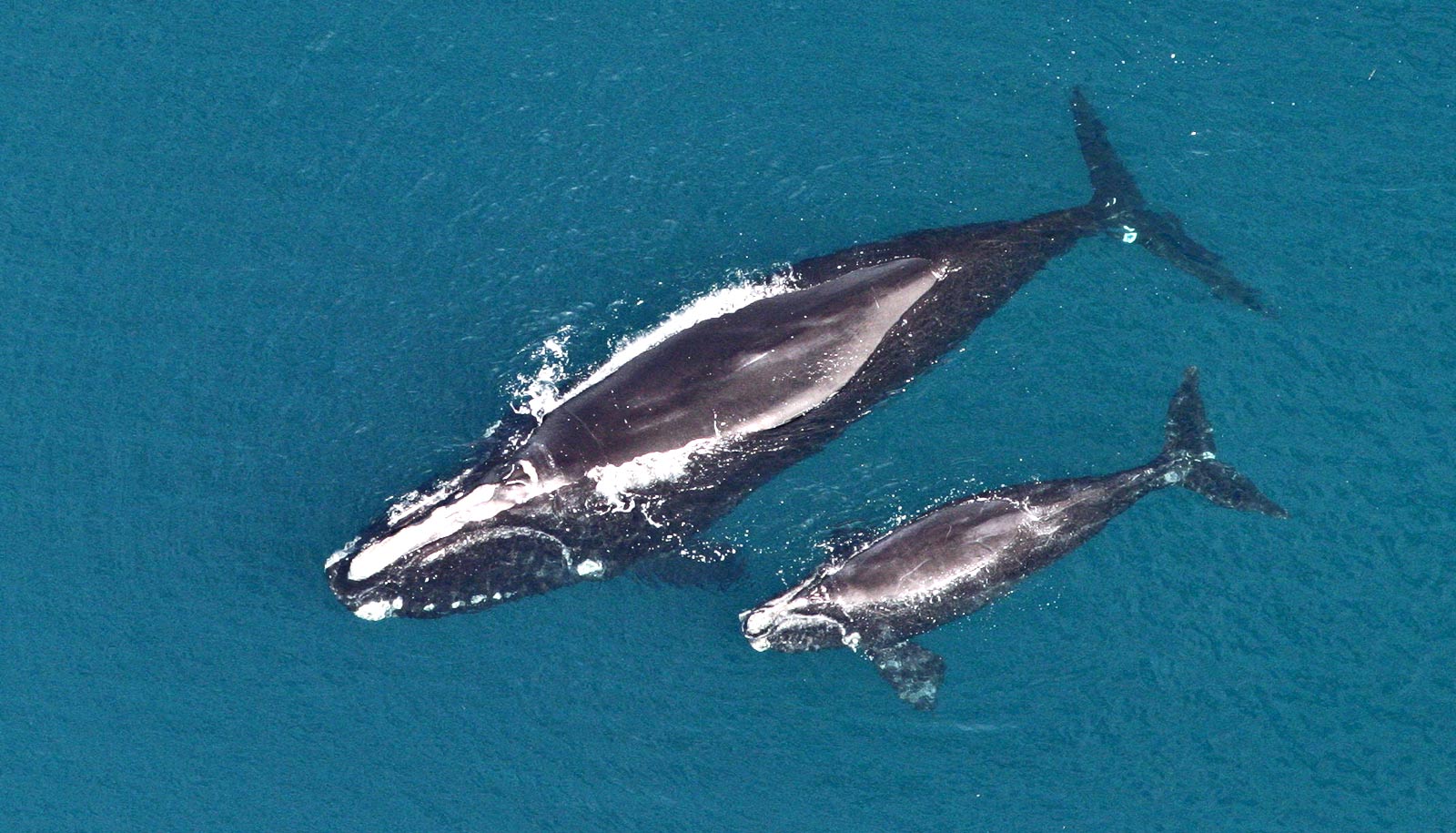

Researchers are hoping to increase public awareness about the dangers facing the North Atlantic right whale, one of the most endangered whale species in the world.

Assessing the welfare of animals in human care, including livestock and those living in zoos and aquaria, has, over time, translated into improved quality of life for these animals, as well as increased consumer awareness of and support for more humane animal practices.

Welfare assessments are a lot harder to perform on animals in the wild, however, due to their large populations, geographical range, and a lack of standardized tools to assess individual animals.

For a team including researchers from the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University, the welfare of the North Atlantic Right Whale (NARW) in particular—one of the most endangered species of whales in the world—has been a primary concern.

As of 2020, only 336 of these massive marine mammals were left. Their limited population and range have made tracking their health and well-being, along with the physical threats this species faces, more manageable for scientists than is typical.

In a recent paper in the Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, the team reviewed the existing research and data on the welfare of the NARW and used it to develop a prototypical welfare assessment tool geared specifically to this species.

While the scientific community is well aware that these whales are suffering, and have been assessing their health for a while, the nature of the data they gather is not easily interpreted or understood by government agencies and the general public.

As a result, it has been difficult to bring the kind of attention that is needed to secure government funding, affect public policy, or influence consumer behavior concerning these animals.

“The reason for this inaction by the public and the legislative bodies is that there’s not enough noise around [the issue],” says Katherine King, first author of the paper. “It’s because people don’t see these whales every day that no one does anything about it.

“If we can get people behind the idea that this population has a lot of problems that are mostly coming from humans, maybe they can apply pressure to governments and encourage them to create change. Consumers can share their opinions with their dollars and where they purchase their products and what companies they invest in.”

Right whale well-being

The main threats to the NARWs are vessel collisions and entanglement in lobster and crab traps. Because these events rarely kill the whales instantly, they are prone to suffering prolonged deaths by drowning, starvation, or infection—in some cases over the course of many months. Climate change has also had an effect, pushing the whales’ prey, and consequently the whales themselves, further north.

These waters, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, once presented an increased risk of collisions and entanglements. An unprecedented number of right whale deaths occurred in the gulf in 2017, at which point the Canadian government took action to help protect the whales.

The proposed assessment tool consists of a checklist of sorts that documents assorted signs of well-being, such as whether a whale has obvious injuries from a vessel strike, if certain natural behaviors seem normal or compromised, or if a calf is spotted with or without its mother in sight. An overall numerical score—the Total Welfare Score—is then assigned, with a negative score indicating negative welfare, zero indicating neutral welfare, and a positive score indicating positive welfare.

“The hope is that the data gained from this tool will provide more easily digestible information directly showing how right whales are suffering,” says coauthor Melissa Joblon, associate veterinarian at the New England Aquarium.

“Documenting and presenting negative changes in behavior and feeding is easier for the public to understand compared to more scientific data relating to stress hormones in the feces or blow, for example.”

Fishing industry collaboration

While there is more to be done, strides are being made within the fishing industry. Policy efforts have helped to identify areas of the ocean that are critical for the whales to feed in so that fishing vessels can modify their routes accordingly.

The New England Aquarium has also been working for years with Massachusetts lobster fishermen to come up with solutions. Lobster traps line the bottom of the ocean, connected by a network of ropes; the ropes are attached to buoys that bob on the surface of the water. When a whale is caught in one of the ropes, it can end up towing the heavy traps, leading to complex and life-threatening entanglements.

One solution to this is to develop ropeless gear (perhaps using a sonar-based system), allowing commercial fishing and North Atlantic right whales to coexist. In the meantime, the Aquarium has advocated for the implementation of weaker ropes that would break more easily if a whale swam into them. Last year, in fact, the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries approved the broad use of weaker ropes and now provides them free of cost to local fishermen.

“The fishermen don’t like seeing the whales being hurt, nobody likes seeing it,” says Felicia Nutter, a wildlife veterinarian and epidemiologist who contributed to the research paper. “It’s just, how do we get enough recognition of the severity of the issue to get more of a groundswell of support, or the financing, to change to some of these novel or newer types of fishing gear.”

Once the assessment tool has undergone testing and validation, field scientists who study these whales will use it. Ideally, the tool will ultimately promote greater awareness of the whales’ plight, potentially allowing consumers to find out where their lobster was sourced.

“It’s taken a long time, but the sharing of this information helps change consumer opinions and helps create demand for alternatives,” Nutter says. “It has happened with dolphin-safe tuna labeling and free-range eggs, and that’s the direction this is going in.”

Source: Christina Frank for Tufts University