The United States government was genocidal in wars against Native Americans from the 1600s to the 1900s, a new book argues.

Jeffrey Ostler has spent the better part of three decades researching and teaching the thorny legacies of the American frontier. His conclusion: the wars the US government waged against Native Americans from the 1600s to the 1900s differed in a fundamental way from this country’s other contemporaneous conflicts. “Against Native nations and communities,” he says, “it was genocidal war.”

Ostler, professor of northwest and pacific history at the University of Oregon, believes that in their description of the conflicts with Native Americans, mainstream political and historical discourses in the United States have often obscured this deadly distinction.

His new book, Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas (Yale University Press, 2019), is a thorough and unflinching review of the evidence. From his vast survey of tribal histories, Ostler concludes that the massacres evidenced a consciously genocidal impulse.

The most important part of his book’s title, Ostler insists, is the word “surviving.”

Based on rigorous attention to treaty language, military records, demographic data, and the actual words of participants, Surviving Genocide documents the murderous intentions that lurked beneath the idealized self-imaging of a young American nation.

“In order to have a ‘land of opportunity’ required space to expand,” Ostler notes. “Early American senses of ‘freedom’ fundamentally depended upon the taking of Native lands—which almost inevitably would lead to the taking of Native lives.”

From the beginning, he believes, US leaders understood and embraced this grim calculus. However, they obscured their true aims with a series of self-serving narratives built around the ideal of “civilization.” At first, this was held forth as a precious and necessary gift the colonizers were offering to Indigenous populations. Later, “defending civilization” would be invoked as justification to kill them.

“A major theme of my book is something I call ‘Indigenous awareness of genocide,'” he says. “The oratory of resistance leaders like Tecumseh shows they recognized that whites intended to kill them and steal their lands.”

In 1775, the Cherokee chief Tsi’yu-gunsini or “Dragging Canoe” noted:

“Whole Indian Nations have melted away like snowballs in the sun before the white man’s advance. They leave scarcely a name of our people except those wrongly recorded by their destroyers… Not being able to point out any further retreat for the miserable Tsalagi (Cherokees), the extinction of the whole race will be proclaimed.”

He was speaking in opposition to a treaty that proposed the Cherokees sell off 20 million acres of homeland—a large portion of present-day Kentucky and Tennessee. This tension exploded with the commencement of independence hostilities in July 1776; some Cherokee leaders sided with the British, and in response the US charged thousands of colonial troops with “the utter extirpation of the Cherokee Nation.”

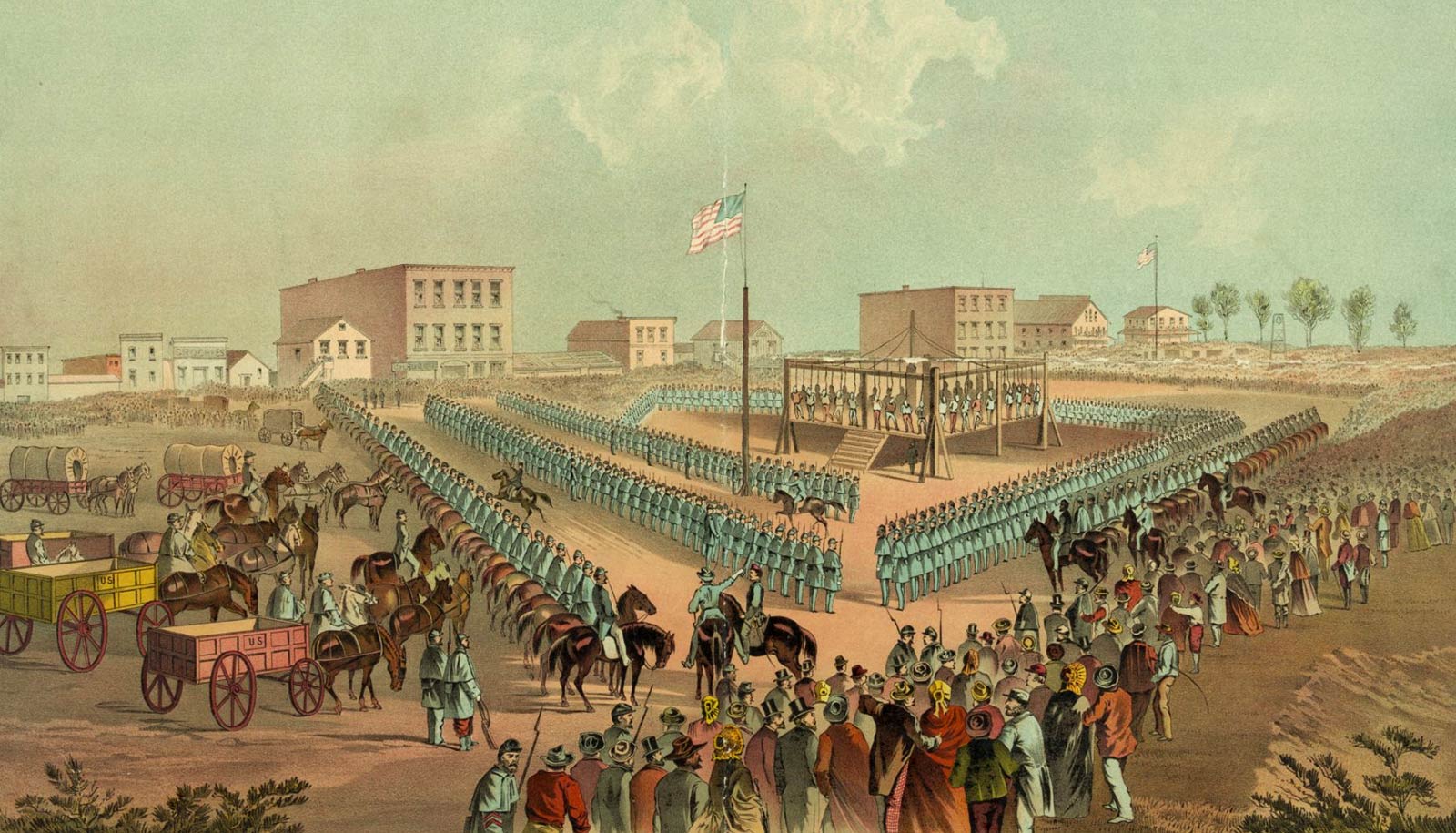

“During this conflict and others in the so-called Indian Wars, attacking whole communities of Native men, women, and children was planned policy of the US government and army,” Ostler says.

Of course, the intention to commit genocide is not sufficient to ensure its results. Native nations and communities persisted. Like the Cherokees, some that were displaced claimed new homelands, laying the foundations of their perseverance to the present day. And through armed struggle, diplomacy, spiritual fortitude, and cultural stamina, a few eastern tribes overcame tremendous odds and retained portions of their ancestral homelands.

The Potawatomi of Michigan, for example, offer a striking example of political resistance, Ostler says.

Traditional residents of the Great Lakes region, most Potawatomis were displaced farther west following the Treaty of Chicago in 1833. But Leopold Pokagon, leader of the tribe’s Catholic converts, obtained the support of a Michigan Supreme Court justice and negotiated an agreement allowing his community of around 280 people to remain on their traditional homelands. Later in the century, other Potawatomi bands returned to Michigan and established communities. In time, with struggle, these groups also attained land and federal recognition.

The most important part of his book’s title, Ostler insists, is the word “surviving.”

Ostler’s second volume will cover regions of the continent west of the Mississippi River. He can’t predict when he’ll finish it—but notes he’s especially looking forward to the challenge and responsibility of digging into colonialism’s painful history close to home in the Pacific Northwest.

“Here in the Willamette Valley, the University of Oregon is on land that was forcibly taken from the Kalapuya people,” he notes. “Wherever we live in America, I believe any of us is well served to learn the history of the land’s original inhabitants, and to acknowledge the extremes of violence in our own history by calling it what is was: genocide.”

Source: Jason Stone for University of Oregon