A new screening process could dramatically accelerate the identification of nanoparticles suitable for delivering therapeutic RNA into living cells.

The technique would allow researchers to screen hundreds of nanoparticles at a time, identifying the organs in which they accumulate—and verifying that they can successfully deliver an RNA cargo into living cells.

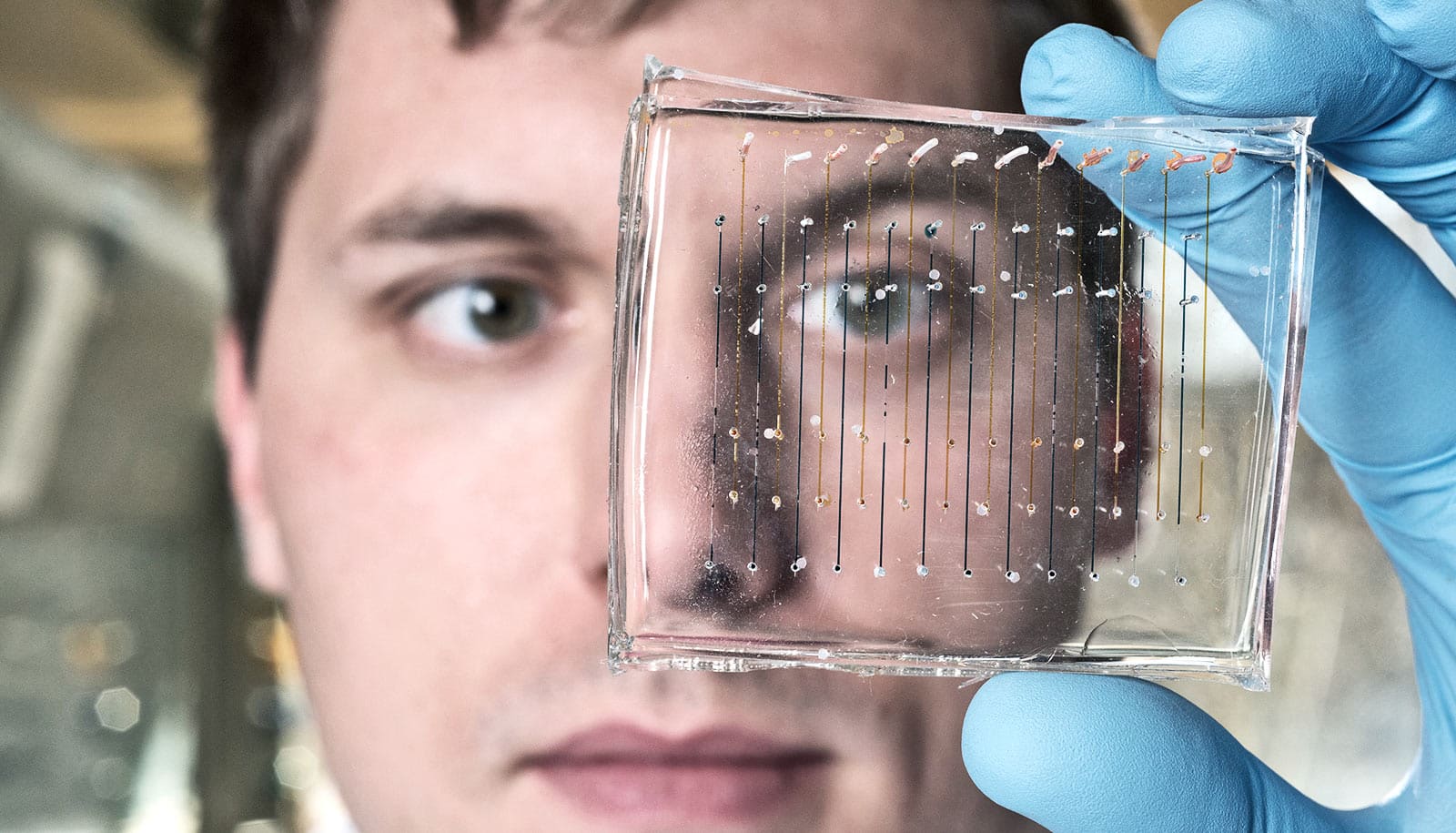

Based on work known as “DNA barcoding,” the technique inserts unique snippets of DNA into as many as 150 different nanoparticles for simultaneous testing. Researchers then inject the nanoparticles into animal models and allow to travel to organs such as the liver, spleen, or lungs. Genetic sequencing techniques then identify which DNA-labeled nanoparticles have reached specific organs.

In a paper which appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers describe taking the process a step farther to verify that the nanoparticles have entered the cells of the specific organs.

Seeing red

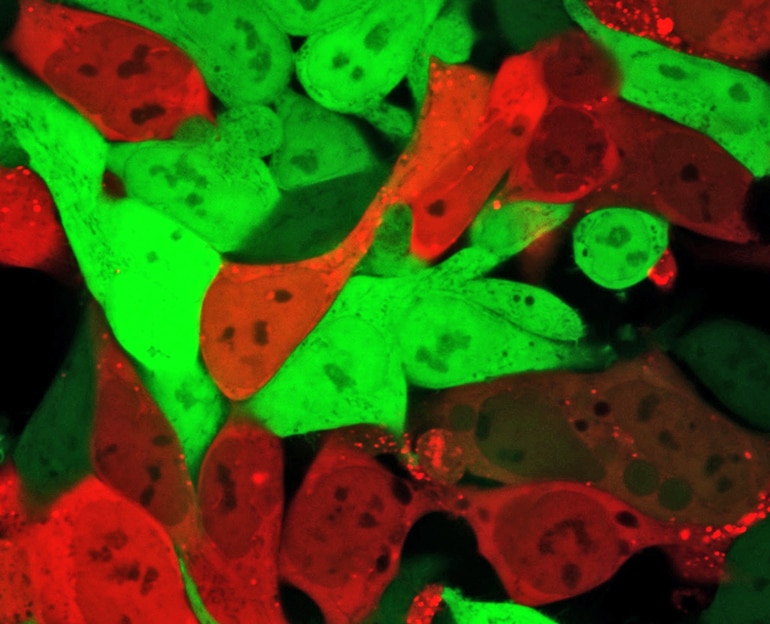

In addition to the DNA barcode, the researchers inserted into each nanoparticle a snippet of mRNA that is turned into a protein known as “Cre.” The Cre protein generates a red glow, identifying cells that the nanoparticles have entered and successfully delivered the mRNA drug, allowing the researchers to identify which nanoparticles can deliver RNA drugs to the cells of the specific organs.

“This technique, known as Fast Indication of Nanoparticle Discovery (FIND), will allow us to identify the right carrier far more quickly and less expensively than we have been able to do in the past,” says James E. Dahlman, assistant professor in the biomedical engineering department at Georgia Tech and Emory University. “As a result, the odds that we will be able to find carriers for specific tissues should increase dramatically.”

The FIND technique would replace in vitro screening, which has limited success at identifying nanoparticle carriers for the genetic therapies.

Therapies based on RNA and DNA could address a broad range of genetically based diseases, including atherosclerosis, where such therapies may be able to reverse the buildup of plaque in arteries. Nanoparticles used to deliver RNA and DNA into cells are made from several ingredients whose levels can vary, creating the potential for tens of thousands of different nanoparticles. Finding the right combination of these ingredients to target specific cells has required extensive trial-and-error discovery processes that have limited the use of RNA and DNA therapies.

Use of the DNA barcoding process allows hundreds of possible nanoparticle combinations to be tested simultaneously in a single animal, but until now, researchers could only tell that the combination had reached specific organs. By examining which cells within the organs have the red glow, they can now verify that the nanoparticles carried the barcodes and delivered functional mRNA drugs into the cells.

Delivering genetic drugs

In the paper, the researchers report discovering two nanoparticles that efficiently delivered siRNA, sgRNA, and mRNA to endothelial cells in the spleen. The researchers believe their technique can deliver therapeutic RNA and DNA to a wide variety of endothelial cell types, and perhaps also to immune system and other cell types.

“The field has been able to functionally deliver genetic drugs to the liver, and we are now trying to use our technology to deliver to different organs and cell types to enable therapies to treat all of the cell types that are in the liver,” says first author Cory Sago, a PhD candidate in Dahlman’s lab. “Now that we have a system that allows us to probe these questions at a very specific level of resolution, we now want to go after other cell types in a more efficient manner.”

Dahlman expects to put the new technology to use quickly.

“We hope to take projects that would ordinarily require years and complete several of them within the next 12 months,” he says. “FIND could be used to carry all sorts of nucleic acid drugs into cells. That could include small RNAs, large RNAs, small DNAs, and large DNAs—many different types of genetic drugs that are now being developed in research labs.”

Technical challenges ahead include demonstrating that identifying an affinity for mouse organs predicts which particles will work in the human body, and that the approach works for different classes of genetic therapies.

Experimentally, Dahlman’s lab produces the nanoparticles at three formulation stations that require about 90 seconds to produce each of the 250 or so samples. The team then examines the resulting nanoparticles for proper size range—40 to 80 nanometers in diameter—before they purify and sterilize them for injection into the animals.

After three days, the researchers separate cells that are glowing red and sequence the DNA snippets in them to identify which chemical compositions were most successful at entering cells of specific organs. The most promising chemical compositions are used to develop of a new batch of candidate nanoparticles for a new round of screening, which takes about a week to complete.

“We want to evolve the best particles that we can,” Sago says. “Every single one of the components matters, and we work to get each component right for the cell type that we are interested in. There is a lot of optimization required.”

Additional coauthors are from Georgia Tech and Emory University. The NIH/NIGMS-sponsored Immunoengineering Training Program, the Georgia Research Assistantship, the NIH/NIGMS-sponsored Cell and Tissue Engineering (CTEng) Biotechnology Training Program, the National Institutes of Health GT BioMAT Training Grant, the Cystic Fibrosis Research Foundation, the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation, and the Bayer Hemophilia Awards Program supported the research.

This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsors.

Source: Georgia Tech