Our modern interpretation of mermaids first came into view thanks to 19th-century European theater, according to new research.

Mermaids can be larger than life or little, but regardless of stature, most people have basically the same idea of what they look like, says Tracy C. Davis, professor of performing arts at the School of Communication at Northwestern University.

“What they may not realize, however, is that the beautiful, half-human sea creatures depicted in their mind’s eye—with scales to the hips and a double fluked blueish-green fin—weren’t always so endearing,” she says.

This modern interpretation of the mermaid form stems from performances and depictions in 19th-century theatrical productions, according to new research from Davis, who is also a professor of theater and English.

The changing form of mermaids

Davis based her paper on research in Europe’s largest theater archive at Cologne University’s TWS, a repository of the graphic design of theater, including images from composer Albert Lortzing’s opera Undine, which opened in Germany in 1845 and is still performed today.

Davis sees the Danube water-spirit Undine as pivotal in the 200-year transformation from a multi-formed—often malevolent—water creature that could feature seal-like fur, two tails, smooth eel-like skin, or pass as is in human form. In contrast, today’s ubiquitous and beautiful mermaid figure fills toy aisles and appears on an estimated 4 billion Starbucks’ coffee cups each year.

The popularity of Undine took place at the same time as another global phenomenon: the first public aquarium opened at the London Zoo in 1853. Never before had the general public been able to explore the underwater world with such ease. Technological advances also helped artists create lifelike recreations of seascapes, which created a new level of thought and empathy for sea life.

On stage, Undine looked for ways to bridge a mermaid’s life on land and at sea.

“Designers looked for ways to convey a mermaid’s being and they did so using things like skirts with shells at the hem and through coral and red stockings. These ‘early’ mermaids still had legs because they were of two worlds and needed to move on stage,” Davis says. “This motif, however, continued to evolve.”

Looking through images in the TWS archive, Davis realized that by 1876, in a performance of Wagner’s Das Rheingold, mermaids moved around on wheeled contraptions with a longer skirt that represented a tail. The next 100-plus years of theater see these techniques repeated—legged mermaids or mermaids with “tails” that needed moving.

“All of these ideas merge in Disney’s Broadway production of the Little Mermaid in 2008,” says Davis, noting that productions of the same show in Tokyo and The Netherlands relied on the “flying mermaid” technique. “On Broadway, they gave Ariel a tail and shoes on wheels so that she could move independently. She still has legs, but viewers focus in on the tail because that is what we’ve been trained to expect.”

From the stage to the gig economy

Davis’ interest in mermaids began serendipitously at a performance studies conference in 2015 in the Bahamas. At Dean’s Blue Hole, she began conversing with a Danish sociologist conducting interviews on the growing freediving culture.

“I was a bit mesmerized by this athletic performance that was taking place where no spectator could view it, while at the same time I observed all of this action taking place above the surface in support of the divers,” Davis says. For the past decade, Dean’s Blue Hole, which has a depth of 663 feet, has played host to the world’s preeminent freediving competition.

The trip inspired Davis to work on a follow-up project with Sara Malou Strandvad, now at the University of Groningen in The Netherlands, that explored “mermaiding” as an aesthetic, performance-based analog of freediving.

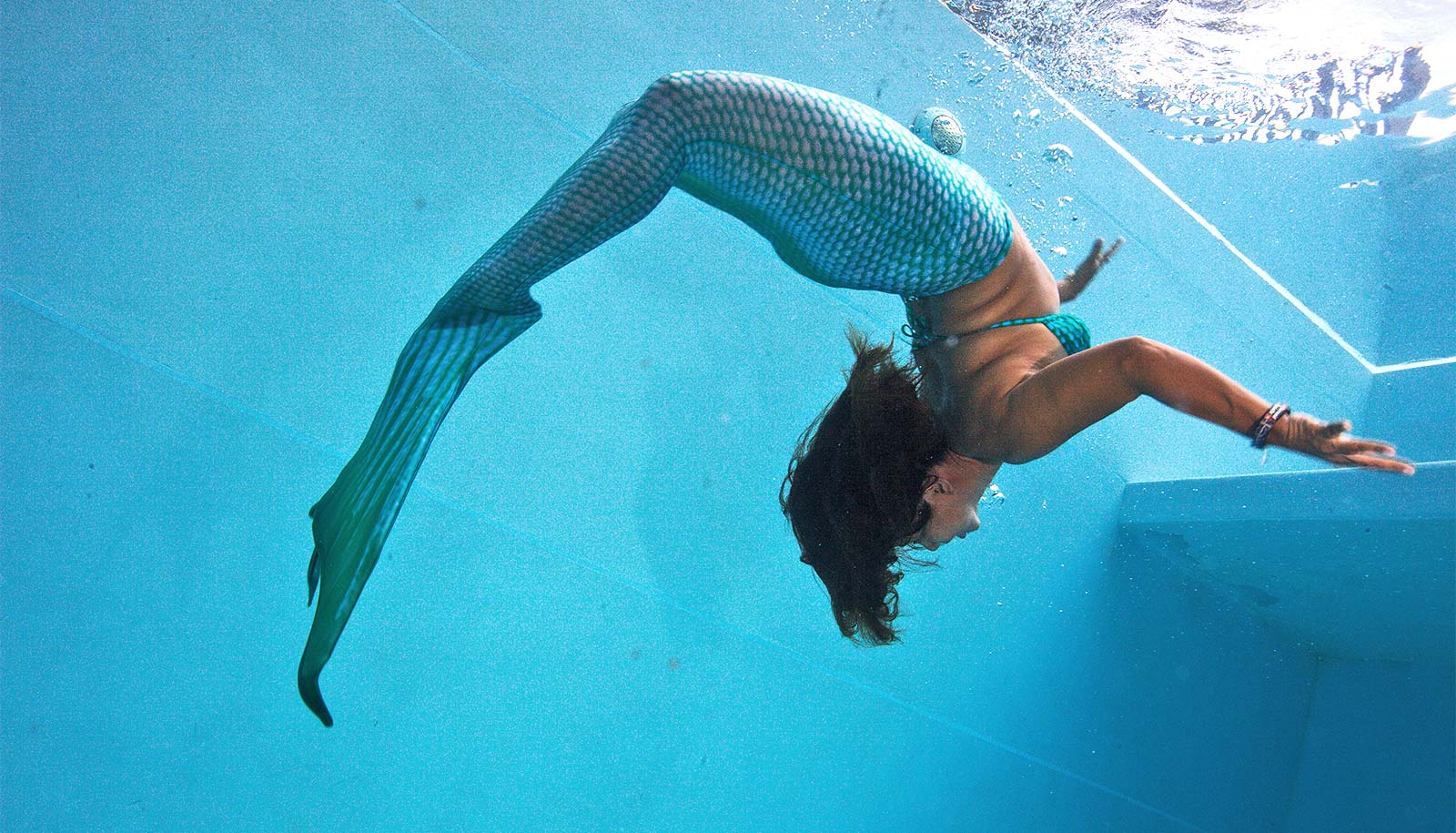

Mermaiding—the act of wearing and/or swimming in a costumed tail—has exploded as both a hobby and profession in the 21st century, says Davis. She attributes the trend in part to the success of Disney’s The Little Mermaid, two Australian TV shows about teenage mermaids, and other mass media products that have brought the mythical creatures into the mainstream.

“For amateurs, mermaiding is largely about dressing in a gorgeous outfit, getting their hair and makeup done, and sitting on a rock for vanity photographs,” says Davis. “For professionals, however, it’s an extremely technical endeavor that is predicated on the idea of appearing natural while being submerged in water.”

Later this year, Davis and Strandvad are publishing research based on observations and interviews with people who perform as mermaids in aquariums at Copenhagen, Munich, Paris, and Denver.

Dozens of aquariums throughout the world hire mermaids—some for entertainment purposes, and others to help deliver a message of ocean conservation. For instance, mermaids in Paris perform alongside a biologist in a performance meant to both amuse and inspire ecological awareness.

“Professional mermaids take breath-holding very seriously,” says Davis, explaining that many performers will submerge for 45 seconds, surface for 30 seconds, and repeat the process for up to 30 minutes, all while assuming the mythos of a mermaid. “The aquarium becomes this perfect stage—an ocean where no ocean exists—with a captivated audience. It creates a niche employment opportunity for the performers.”

The next phase of Davis’ research is based on more than four dozen interviews with “mermaids” and people who work in the mermaiding industry (tailmakers, teachers, photographers, etc.). The work will focus on how mermaiding has emerged as an employment category in the so-called gig economy. Over the past four years, Davis says she has met “mermaids” who are veterinarians, experts in spearfishing, and doctoral students.

For people aware of the bulk of her work—Davis has written 10 books on topics ranging from the economics of the British stage to the historical and sociological relevance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin—mermaiding may seem a bit of a tangent for such a serious scholar. She views her recent investigations as part of a larger whole.

“It makes sense to me because I’ve always been interested in women’s work in theater,” says Davis. “Exploring the social, economic, and aesthetic practices in mermaid performance and discovering that today’s mermaid motifs and traditions are steeped in European theater, brought me to an emerging industry of entrepreneurship.”

Davis’ paper will appear later this year in Theatre Journal.

Source: Roger Anderson for Northwestern University