Medical debt extended people’s period of homeless by an average of two years, according to research in Washington state’s King County.

Medical bills were the primary source of debt among people in the study.

Research shows that medical debt burdens millions of Americans: Depending on how you define “medical debt,” studies from nonprofits and academic institutions generally show from 16% to 28% of adults carry that burden.

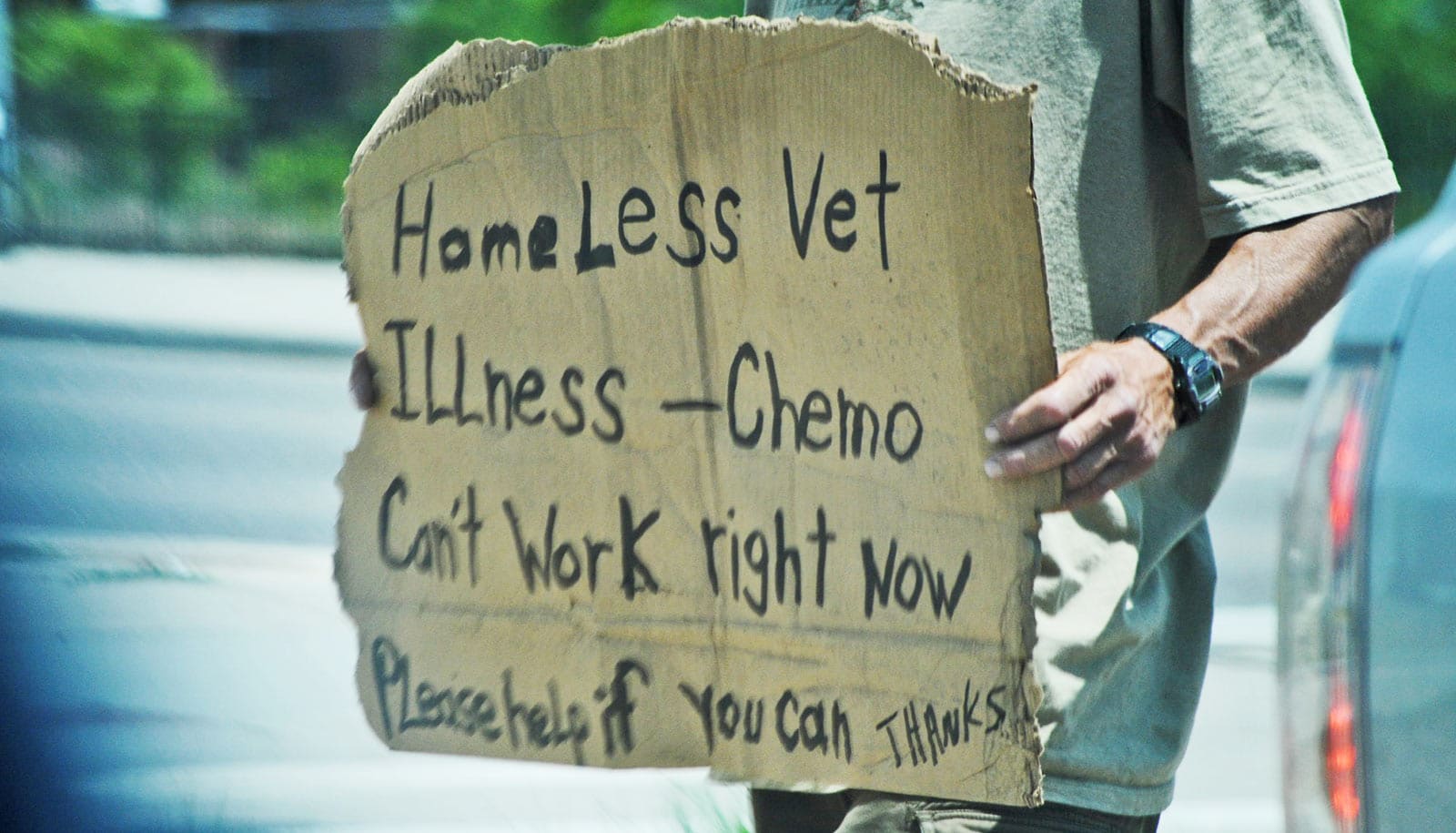

And medical debt and housing instability often go hand in hand.

“So many people have lost their jobs, and then they lose their health insurance. They may not be able to pay even small medical bills or co-pays and still have rent or mortgage payments. If they get sick with coronavirus, or some other medical condition, this can be the perfect storm that puts people out on the street and increases the time they spend there,” says Jessica Bielenberg, who conducted the study for her master’s thesis from the University of Washington’s School of Public Health.

The study appears in Inquiry: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing.

Little research has been done linking medical debt and homelessness, Bielenberg points out. While her study did not find a direct causal relationship between the two, it did determine that among those experiencing homelessness, the inability to pay off medical bills, even a few hundred dollars, was associated with considerably more time spent unhoused.

In about one-third of cases, the amount of medical debt was relatively small—less than $300.

Bielenberg and her coauthors worked with two Seattle organizations supporting shelters and encampments for the homeless: SHARE and Nickelsville. The team surveyed 60 adult residents about their health and financial situation, including other debts and past periods of homelessness. Two-thirds of participants were white, 15% were Black, and 7% were Native American.

Participants whose medical bills had been sent to collections had experienced homelessness for an average of 22 months longer than those who hadn’t had such trouble paying bills; Black, Indigenous, and people of color who were unable to pay their medical bills reported being homeless a year longer than white participants with the same financial challenge.

“If Black lives really mattered, we wouldn’t systematically exclude those folks from good jobs—and a good job in America is a job with health insurance,” says coauthor Marvin Futrell, a clinical instructor in the University of Washington department of health services and an organizer with SHARE and Nickelsville.

In all, more than 80% of participants reported having debt of some kind, such as doctor bills, student loans, credit cards, or payday loans. Of those participants, 68% reported medical debt, the majority of which had gone to collections.

In about one-third of cases, the amount of medical debt was relatively small—less than $300. That underscores what, for many people, can be a domino effect, Bielenberg says: One lost job, or lack of health insurance, can saddle a person with debts they have to prioritize, if they can pay them at all.

Medical debt, health insurance, and homelessness

Medical debt is a different kind of debt than, say, outstanding credit card bills or student loan payments, which can be protective against homelessness in the short term, Bielenberg explains. Someone making student loan payments has an education, which can enhance their earning power, while credit cards and payday loans can cover basic necessities, even though they come with high interest rates. Medical debt, by its nature, stems from an illness or injury and may accompany job loss or lack of health coverage.

But what might be perceived as a safety net—health insurance—wasn’t always that, Bielenberg found. Two-thirds of participants were enrolled in Washington’s Medicaid program, Apple Health, while others received coverage from Medicare, the Indian Health Service, or the Veterans Health Administration. Some 16% reported having no insurance coverage.

Insurance doesn’t always cover everything, Bielenberg says, and even the comfortably insured may lose track of costs that are their responsibility.

Time to change the system?

The study didn’t examine or advocate for specific solutions, but Bielenberg suggested further research, with larger and more diverse participant pools, could bolster arguments for policy change or new support programs.

“Fortunately and unfortunately,” Bielenberg says, “we are in a time of considerable turmoil. Sometimes these moments are the perfect time to completely rethink our ways of doing things. The US could join the vast majority of countries in the world and simply offer universal health coverage. We spend twice per person on medical care than any other country, so we obviously are doing something wrong.”

Bielenberg received a stipend from the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice to support her graduate studies.

Source: University of Washington