Untethered magnetic needles can perform less invasive, more precise surgery, researchers report.

Imagine a tiny, untethered needle that can enter the body through an incision no larger than a pin prick to perform biopsies, suture wounds, and even deliver cancer-fighting chemotherapy directly to tumors.

Controlled by externally applied magnetics forces—no attached, guiding wires, or human or robotic hands—these miniscule tools promise a future of more precise, safer, and far less invasive surgery, experts say.

But there’s a hitch: As devices get smaller, so does their response to the magnetic forces that cause them to move and steer their course.

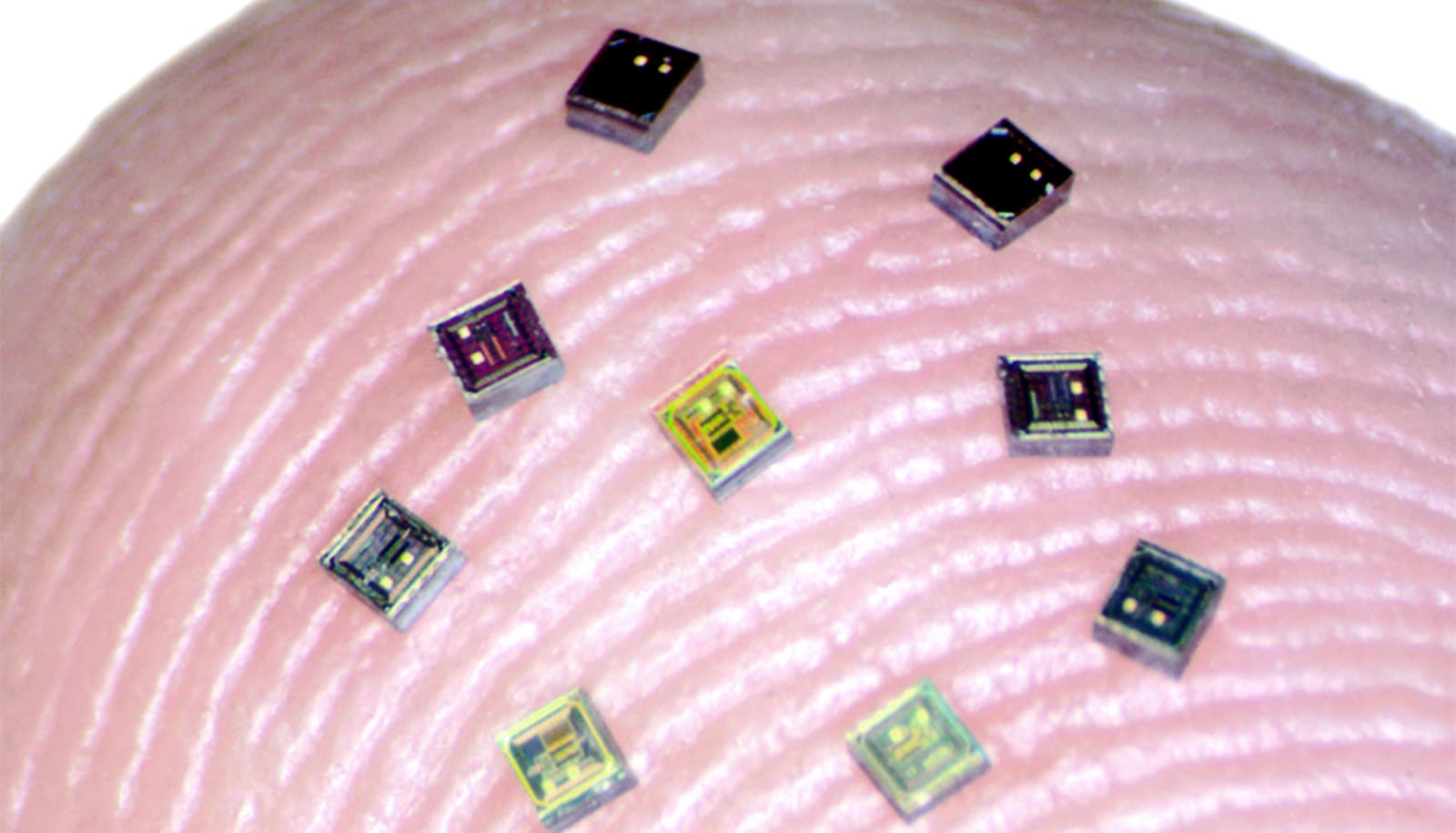

“These extremely small tools have the potential to revolutionize medicine, but as anyone who has played with magnets knows, size is important,” says Axel Krieger, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering.

“The smaller the surgical tool, the less invasive the surgery, but also the weaker the device’s response to magnetic force. One of the biggest challenges facing us is how to make sure that these mini-tools can be moved with enough force to penetrate tissue and do the job they are there to do.”

Krieger and colleagues have a solution: a surgical needle equipped with small magnets inside that, when stimulated by the externally applied forces, slip from one end of the needle to another, tapping against a rigid plate and supplying ample force to penetrate tissue. They call their device the “Pulse Actuated Collisions for Tissue-penetrating Needle,” or MPACT-Needle.

For their experiments, Krieger and his team connected a slender thread of suturing material to the needle, using a joystick connected to a computer to deliver commands that enabled the MPACT-Needle to perform surgical suturing on a sample rabbit cornea.

“We proved that these tiny magnetic needles can have strong enough forces to perform delicate surgery with limited invasiveness,” says Onder Erin, a postdoctoral fellow in mechanical engineering, and lead author of the paper in Advanced Intelligent Systems. “I can envision a time when our device will also be used to perform biopsies, and even deliver therapeutics and chemotherapy directly to tumors.”

The team’s next step is to develop better, more accurate motion-control algorithms equipped with imaging modalities to precisely control the movement of the device, making surgeries and procedures safer.

Team members say that if the technology becomes successful, the new magnetic needles would make it possible to access hard-to-reach, delicate areas of the body, such as the bile duct, to deliver drugs directly to tumors, extract biopsy samples, or suture a wound rapidly and effectively to stem internal bleeding.

Additional coauthors are from the University of Maryland, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, and Johns Hopkins.

The National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health’s National Eye Institute and National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering funded the work.

Source: Johns Hopkins University