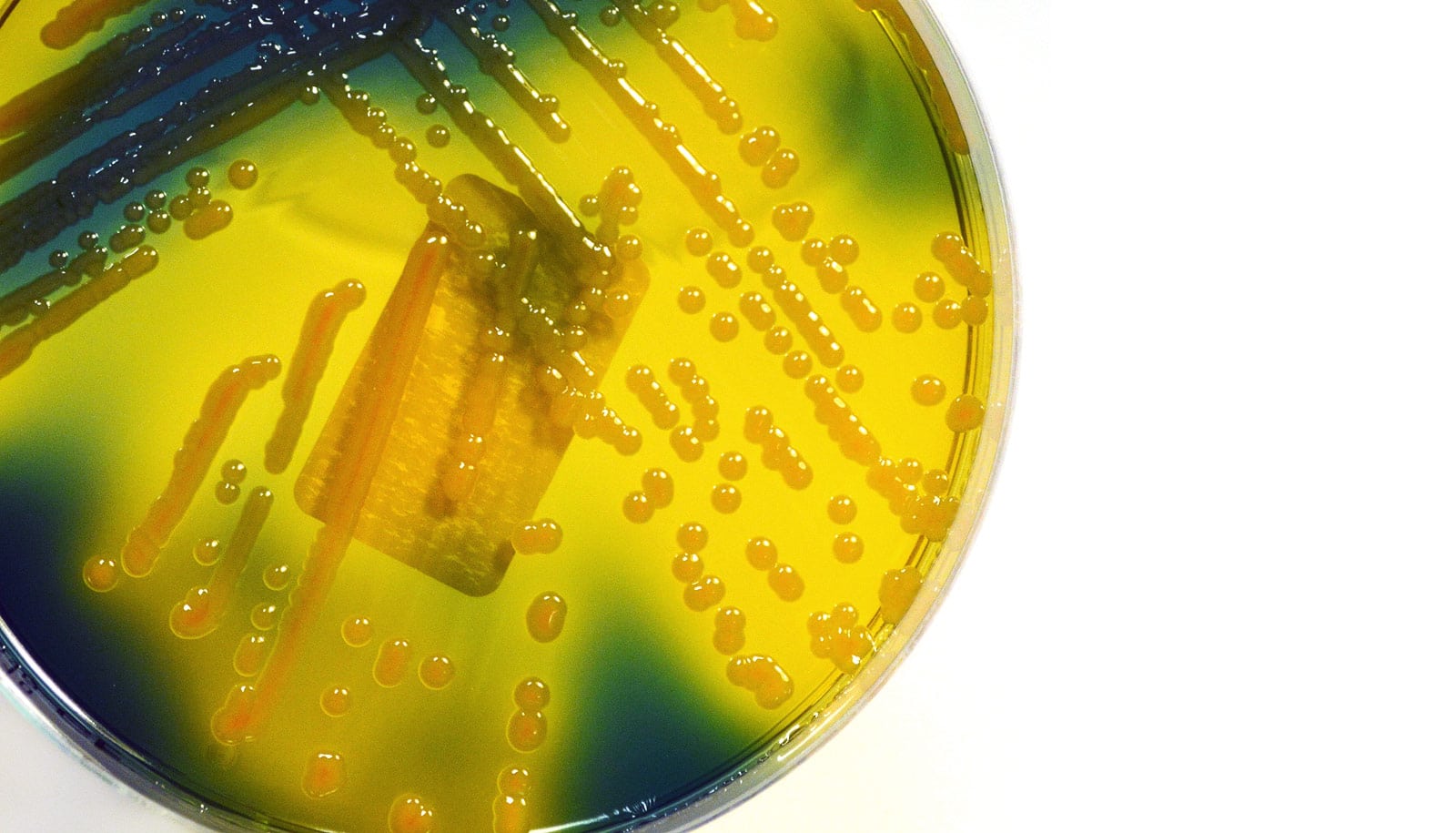

Scientists have discovered several biomarkers that can accurately identify what could be the next superbug—hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The pathogen infects completely healthy people and can cause blindness in one day and flesh-eating infections, brain abscesses, and death in just a few days. What’s more, it’s also resistant to all antibiotics.

Until now, there has been no accurate method for distinguishing between the hypervirulent strain from the classical strain of K. pneumoniae, which most often occurs in the Western hemisphere, is less virulent, and usually causes infections in hospital settings.

“Presently, there is no commercially available test to accurately distinguish classical and hypervirulent strains,” says Thomas A. Russo, professor of medicine in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University at Buffalo. “This research provides a clear roadmap as to how a company can develop such a test for use in clinical laboratories. It’s sorely needed.”

“A bug that’s both hypervirulent and challenging to treat is a bad combination.”

Further, a definitive diagnostic test would not only optimize patient care but would also allow researchers to perform epidemiologic surveillance to track how frequently the hypervirulent strain causes infection and how frequently it acquires antimicrobial resistance, Russo says.

While the assumption is that the pathogen spreads from person to person through food and water, the mode of transmission is unknown.

Both strains of K. pneumoniae can be deadly, Russo says, but the classical strain is more likely to infect patients with underlying disease, or who are immune-compromised and hospitalized.

By contrast, the hypervirulent strain can infect healthy, young people, causing sudden, life-threatening complications, ranging from liver or brain abscesses to flesh-eating infections. While it’s currently less likely to be antibiotic resistant, these strains continue to evolve. Classical strains are more likely to be antimicrobial resistant.

“What’s increasingly concerning is the growing number of reports that describe strains of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae that are antimicrobial resistant,” Russo says. “A bug that’s both hypervirulent and challenging to treat is a bad combination.”

An antimicrobial-resistant hypervirulent strain can develop in one of two ways, he explains: either by acquiring antimicrobial-resistance genes, or when an antimicrobial-resistant classical strain acquires hypervirulence.

“The latter mechanism is what caused the deaths of five patients in the intensive care unit of a hospital in Hangzhou, China, which was reported early this year,” Russo says.

Since clinical laboratories have no test to detect the hypervirulent strain, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to properly diagnose it, researchers say.

The so-called string test, currently used in some cases to distinguish the classical and hypervirulent strains, is not consistently accurate, according to research. It’s especially problematic, Russo says, in North America and Europe, where there is a low prevalence of the hypervirulent strain.

“Many clinicians are unaware of the hypervirulent strain,” he adds. “And because there’s no diagnostic test, the clinical lab can’t give them a heads up.”

Russo and his coauthors knew that the hypervirulence of K. pneumoniae is mostly due to genes located on a large virulence plasmid, DNA that is independent from the chromosome. They hypothesized that some of these genes, including those producing iron-acqusition molecules called siderophores, might be good biomarkers. This proved to be the case.

They also found that higher concentrations of siderophores predicted hypervirulence. They then validated the identified biomarkers in a mouse infection model.

“The advantage of identifying these genetic biomarkers is that they can be developed into rapid nucleic acid tests, and if approved by the Food and Drug Administration, would then provide clinicians with an accurate method to quickly determine if a patient is suffering from an infection due to the classical or hypervirulent strain,” Russo explains.

Such a test will not only benefit patients and possibly save lives, he says, but will also prove critical in learning more about hypervirulent K. pneumoniae.

Colonoscopies lead to more infections than experts thought

“For example, we don’t know the frequency of infection by hypervirulent K. pneumoniae in different parts of the world,” he says. “We know it infects all ethnic groups, but so far it’s been described most often in Asians, particularly in Asian Pacific Rim countries.

“Is that because hypervirulent K. pneumoniae is more commonly acquired in that part of the world but doesn’t necessarily result in infection, or because some Asian populations are, for some reason, more susceptible to it? Now we can begin to study those kinds of epidemiological questions.”

Trio of antibiotics gangs up to kill superbugs

The findings appear in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

Other coauthors are from the University at Buffalo, McGill University, the University of Iowa, National Taiwan University, the University of Oxford, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and the University of Minnesota.

The National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the University of Oxford/Public Health England Clinical lectureship, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the work.

Source: University at Buffalo