Fear of encouraging sexual activity is not a common reason why parents avoid immunizing their kids against the sexually transmitted human papillomavirus, according to a new survey analysis.

Doctors frequently cite parental fears of inciting early sexual activity as a barrier to advocating HPV vaccination for their patients. But the numbers show that far more significant obstacles include parental fears about vaccine safety, the belief that the vaccine is unnecessary, lack of parental knowledge about HPV, and the lack of a doctor’s recommendation, researchers say.

The vaccine has shown promise for stemming long-rising rates of cancers HPV transmits, including an estimated 31,500 US cases annually of cancers of the cervix, vagina, vulva, oropharynx, and anus. The US Food and Drug Administration approved the vaccine in 2006 for girls and in 2009 for boys as young as 9.

“We think all physicians need to be champions of this vaccine that has the potential to prevent tens of thousands of cases of cancers each year,” says lead author Anna Beavis, an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Johns Hopkins University. “Providing a strong recommendation is a powerful way to improve vaccination rates.”

Survey says

Worldwide studies have shown the vaccine to be virtually 100 percent effective and very safe. The vast majority of side effects are minor.

Despite a recommendation by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices to include the vaccine in routine childhood vaccination, current use in the United States remains relatively low. In 2016, only 50 percent of eligible females and 38 percent of eligible males had completed the vaccine series.

For the study, which appears in the Journal of Adolescent Health, researchers mined data from the 2010–2016 National Immunization Survey-Teen, an annual vaccine monitoring survey the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted.

NIS-Teen collects information from a nationally representative sample of parents about their children’s vaccine usage. Vaccine rates are verified with information collected from each child’s physician.

The survey included questions about whether parents planned to vaccinate their children against HPV if they hadn’t already—and, if not, why they were choosing not to. The question was open-ended, allowing parents to name their reasons rather than choose from a list.

Boys and girls

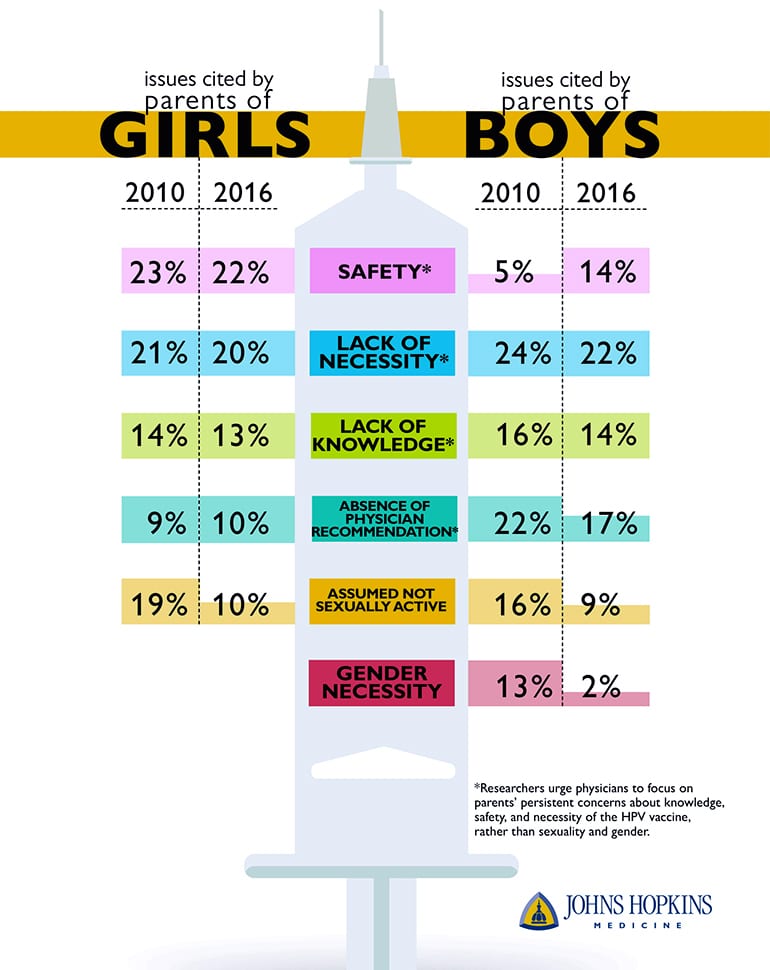

The researchers sorted the answers into categories, separating the data by year and by children’s gender.

For girls, the top four reasons parents gave for not vaccinating stayed relatively stable between 2010 and 2016. These included safety concerns (which 23 percent of non-vaccinating parents in 2010 cited versus 22 percent in 2016), lack of necessity (21 percent versus 20 percent), knowledge (14 percent versus 13 percent), and physician recommendation (9 percent versus 10 percent). Those citing their child’s lack of sexual activity shrank by nearly half over these years (19 percent versus 10 percent).

For boys, the top reasons parents cited in 2010 all decreased over time. These included lack of necessity (24 percent versus 22 percent), physician recommendation (22 percent versus 17 percent), knowledge (16 percent versus 14 percent), child’s lack of sexual activity (16 percent versus 9 percent), and gender (13 percent versus 2 percent). But concerns about safety increased from 5 percent in 2010 to 14 percent in 2016. The researchers are not sure why that is.

The findings demonstrate that parents are less concerned with the HPV vaccine’s relation to gender and sexual activity, and that public health campaigns should focus on parents’ true concerns, the researchers say.

They say family practice physicians, gynecologists, and pediatricians should focus on the fact that HPV vaccine has enormous potential to prevent cancers and a strong safety record.

HPV will infect up to 80 percent of sexually active Americans at some point during their lives, according to the American Sexual Health Association. The majority of these infections resolve without symptoms.

HPV is sexually transmitted and can cause genital warts and benign tumors on the aerodigestive tract, a condition called laryngeal papillomatosis. Some strains can cause changes in DNA that encourage the formation of cancers in both males and females.

The HPV vaccine can protect against nine cancer-causing strains of HPV. The recommended dosing schedule for the vaccine now involves two injections if the first is administered before age 15, or three injections if the first is administered after age 15.

Source: Johns Hopkins University