X-ray technology offers new information about the armor worn by the crew on Henry VIII’s warship the Mary Rose.

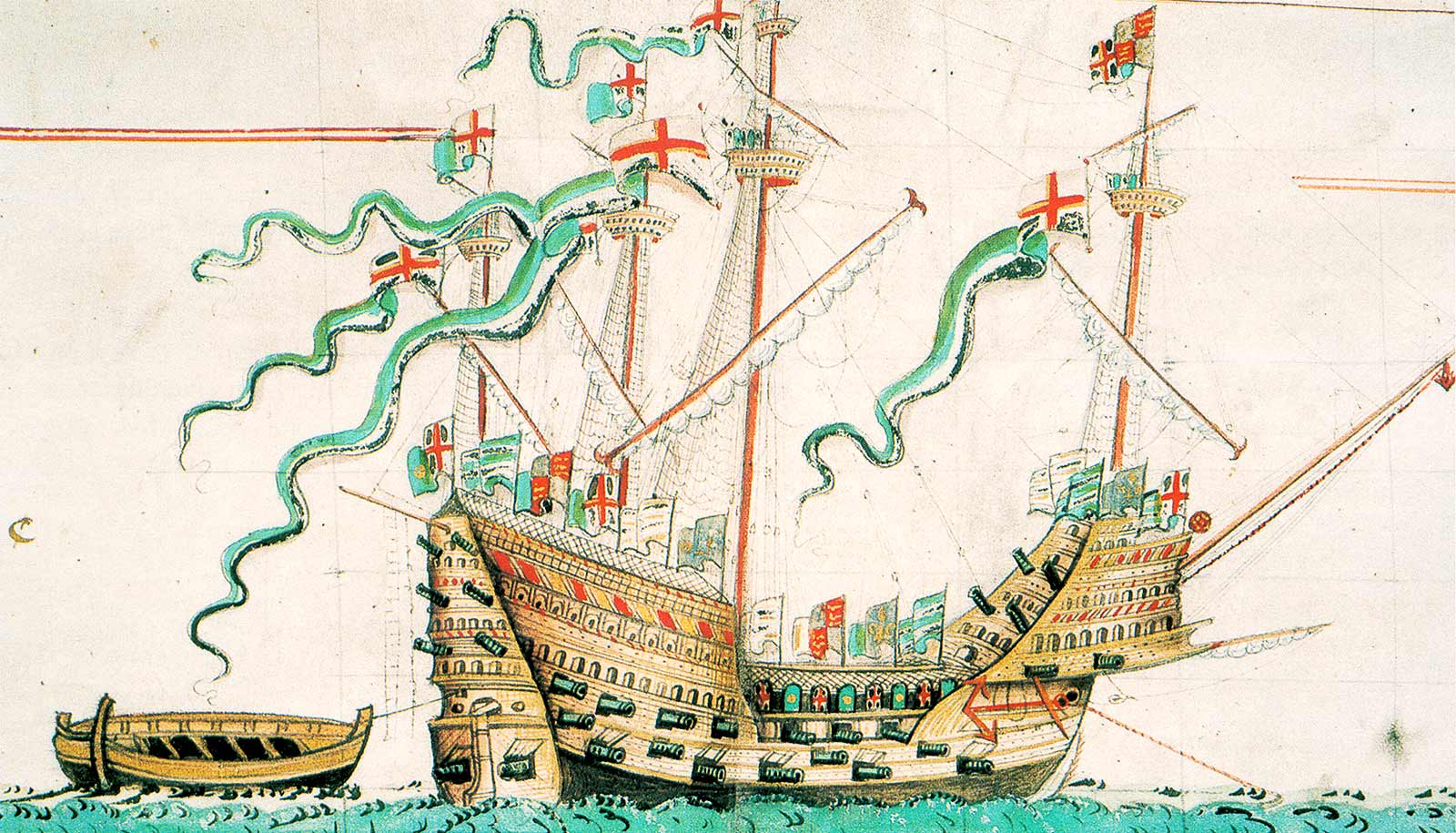

The Tudor warship the Mary Rose was one of the first warships that Henry VIII ordered not long after he ascended to the throne in 1509 and possibly his favorite. On July 19, 1545, it sank in the Solent (the strait between mainland England and the Isle of Wight) during a battle with a French invasion fleet. The ship sank to the seabed and over time silt covered and preserved its remains as a remarkable record of Tudor naval engineering and shipboard life.

In 1982, the remaining part of the hull went to the Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth alongside many thousands of the 19,000 artifacts recovered from the ship. The Eocene clay preserved many of them remarkably well.

Three brass links, which researchers believe to be remains of chainmail, come from the recovered hull of the ship.

By using several X-ray techniques available via the X-ray Materials Science, or XMaS, beamline to examine the surface chemistry of the links, the team determined that the links were manufactured from an alloy of 73% copper and 27% zinc.

“The results indicate that in Tudor times, brass production was fairly well controlled and techniques such as wire drawing were well developed,” says Mark Dowsett, professor emeritus in the University of Warwick’s physics department.

“Brass was imported from Ardennes and also manufactured at Isleworth. I was surprised at the consistent zinc content between the wire links and the flat ones. It’s quite a modern alloy composition.”

The analysis revealed traces of heavy metals, such as lead and gold, on the surface of the links. The findings appear in the Journal of Synchrotron Radiation.

“The heavy metal traces are interesting because they don’t seem to be part of the alloy but embedded in the surface,” says Dowsett. “One possibility is that they were simply picked up during the production process from tools used to work lead and gold as well. Lead, mercury, and cadmium, however, arrived in the Solent during WWII from the heavy bombing of Portsmouth Dockyard. Lead and arsenic also came into the Solent from rivers like the Itchen over extended historical periods.

“In a Tudor battle, there might be quite a lot of lead dust produced by the firing of munitions. Lead balls were used in scatter guns and pistols, although stone was used in canon at that time.”

The research also determined that different cleaning and conservation treatment to prevent corrosion (distilled water, benzotriazole (BTA) solution, and cleaning followed by coating with BTA and silicone oil) were each effective.

“The analysis shows that basic measures to remove chlorine followed by storage at reduced temperature and humidity form an effective strategy even over 30 years,” says Dowsett.

The universities of Liverpool and Warwick own XMaS, which is located in Grenoble, France, at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility.

Source: University of Warwick