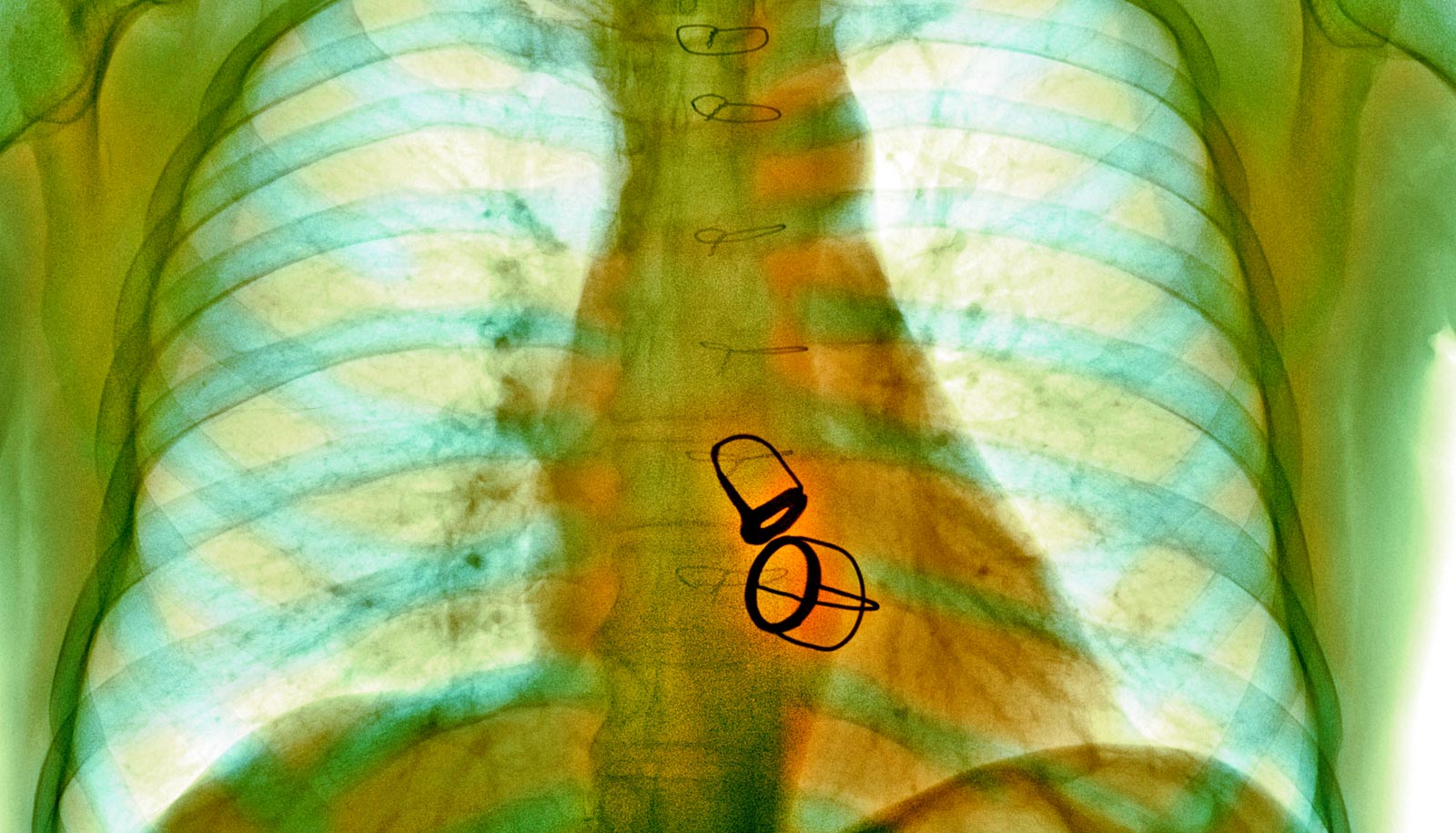

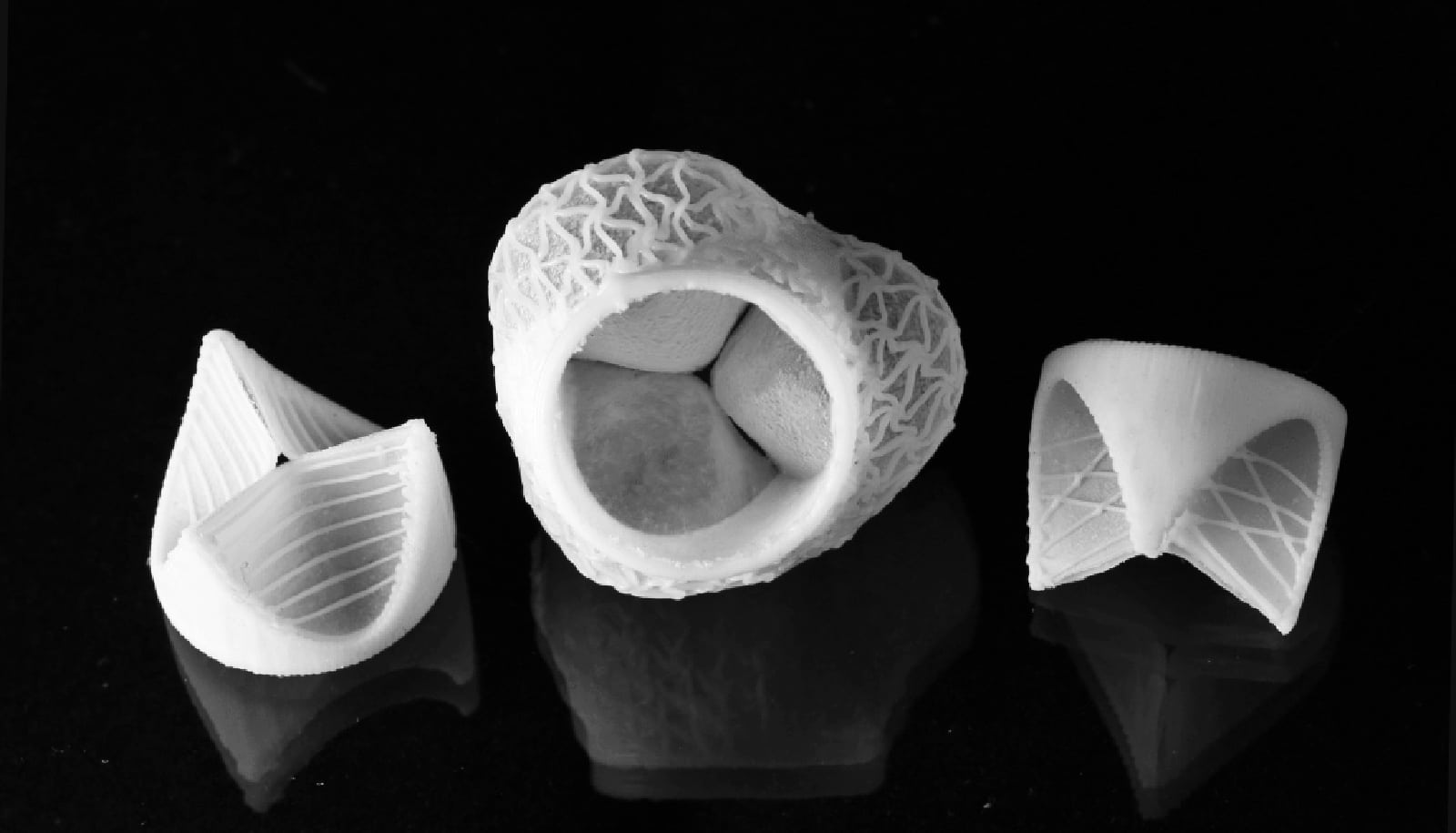

People with heart disease or defective or artificial heart valves have an increased risk of developing a potentially deadly valve infection in the hospital, according to a new study.

Researchers report that new risk factors for the condition have emerged and that an increasing number of patients admitted to hospitals for other diseases are at risk of contracting it.

The study, published in the American Journal of Cardiology, highlights the need for hospitals to develop ways to prevent the serious heart infection, researchers say.

The American Heart Association had recommended that all people at risk for heart valve infections (infective endocarditis)—which bacteria typically cause by entering the bloodstream through the mouth, gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract—take antibiotics.

But in 2007, the guidelines changed to recommend antibiotics only for patients at high risk for infection.

“In the past, infective endocarditis was associated with rheumatic heart disease and most often caused by bacteria in the mouth,” says lead author Abel Moreyra, a professor of medicine at Rutgers University Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

“However, new risk factors, such as intravenous opiate abuse, compromised immune systems, hemodialysis, and implanted heart devices have emerged.”

To understand how guideline changes affected the rate of infections, the researchers analyzed 21,443 records of people diagnosed with infective endocarditis in New Jersey hospitals from 1994 to 2015.

They made a startling discovery: Beginning in 2004 and continuing thereafter, they found a significant decline in the number of patients hospitalized with infective endocarditis as the primary diagnosis for their reason for admission and a significant increase in the number of patients developing the infection in the hospital, or a secondary diagnosis.

In total, 9,191 people hospitalized had infective endocarditis as the primary diagnosis and 12,252 had it as a secondary diagnosis.

Moreyra attributes the decline in primary diagnosis to improved dental care and the rarity today of rheumatic heart disease, where Streptococcus plays a predominant role in the infection.

“However, 60% of infective endocarditis that developed after admission were caused by a different microorganism, Staphylococcus bacteria, which is abundant in hospitals and implicates health care as a possible source of infection,” he says.

This important analysis of the different time trends of primary and secondary diagnosis of infective endocarditis can help hospitals tailor different strategies for the prevention of this potentially lethal infection, Moreyra says.

Source: Rutgers University